The remains of Beirut’s castle along with the uncovered Crusader tower and parts of its Ottoman iteration standing on a limestone promontory. A modern day sewage system runs across the site. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

BEIRUT — Lebanon’s coast is dotted with castles that have stood for hundreds of years. Tourists regularly traipse through the fortresses of Tripoli, Jbeil and Saida. One coastal city is a notable exception: Beirut.

In fact, the capital once had an impressive seaside castle of its own. But since it was built in the 12th century, the cityscape and even the coast of Beirut have shifted dramatically. All that remains of the ancient structures are ruins hidden from the public, blocked from view by the bustling Foch street and the nearby Beirut Souks and Biel. This is not by chance; it results from Beirut’s complex planning and design history.

Uncovering the castle

In the postwar 1990s, Beirut’s central district underwent a thorough excavation that had to be completed before any real reconstruction could begin. The excavation projects included the city’s old souks and their surroundings, near Martyrs’ Square, where the Rivoli theater and lesser-known Byblos cinema once stood. Archeologist Leila Badre led one such dig, which was initially meant to excavate the Phoenician wall and some of the oldest remnants of Beirut, which are mud brick.

“No one was thinking about any medieval thing or castle,” said archeologist Patricia Antaki, who at the time was fresh out of her undergraduate studies at the American University of Beirut and working as part of the team digging at the central Beirut site.

One day, in 1995, as she was working on Bronze age structures, excavator machines were clearing soil behind her when they stumbled across something — giant stone masonry.

“We realized that we were dealing with something completely different,” Antaki said,

They had unearthed a piece of Beirut’s medieval past.

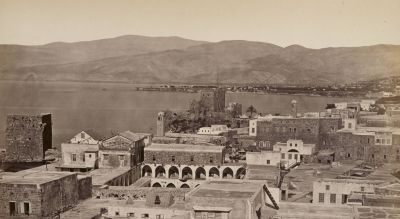

A panoramic view of Beirut including the castle and the watchtower before the construction of the modern Port of Beirut. “Souvenirs d'Orient: Beyrouth” by Félix Bonfils, 1878. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

A panoramic view of Beirut including the castle and the watchtower before the construction of the modern Port of Beirut. “Souvenirs d'Orient: Beyrouth” by Félix Bonfils, 1878. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

History of the castle

The castle is not a single monument. Rather, several castles were built on top of each other, torn down and erected by the many conquerors who moved up and down the coast from the 12th to the 19th century.

The first of them, built in 1125 on the outskirts of the city near Baabda, was more of a watchtower than a defensive fortress. This castle was destroyed in 1157 by an earthquake. The second castle is believed to have been constructed after the earthquake and before the conquest of Saladin. Archeologists estimate that the castle at its current location was built somewhere between 1183 and 1185, at the orders of Raymond III of Tripoli, out of fear that Saladin might capture the city. It took three years to complete the construction.

A later iteration was built in the Ottoman era.

The castle was situated on a rocky cliff that extends into the sea, known as a promontory. Its placement created a natural moat and increased the defensibility of the structure. It had two entrances, one on land protected by a moat and the other facing the sea. The defense of the city at the time relied on the castle itself, and as such, the fortress changed hands between a series of conquering armies.

When Saladin, the Kurdish warrior who recaptured Jerusalem, conquered Beirut, his flag was raised atop the castle. While negotiating with Richard the Lionheart, then-king of England, the castle was one of Saladin's sticking points. If the city were to be returned to the Crusaders, he would first destroy the castle, preventing them from ever using it against him. In any event, the Crusaders failed to reconquer the city then, and the castle survived.

However, after Beirut fell to the Mamluks in 1291, the castle was razed.

Antaki said the Mamluks destroyed the castle for fear that if the Crusaders retook the city, they wouldn’t be able to keep it for long.

In the 14th century, Sultan Barquq built two towers over the ruins of the Crusader castle as well as a small lighthouse-cum-watchtower on an islet near it named Burj al-Musallah. In 1773, Jezzar Pasha, after capturing the city, destroyed the castle and built a much smaller fort in its place. But when the British invaded Beirut in 1840, they bombarded the castle, and so it was abandoned. Starting in the 1880s, the watchtower near it was incorporated into the port of Beirut and was dismantled brick by brick. The stones could have possibly been used elsewhere for other constructions. Antaki noted that this was a common practice at the time, “like the Saida castle that was three times bigger.”

Photo of Burj al-Musallah and parts of the castle in the background. “Beyrouth. Forts ruinés de l'entrée.” Photo by Louis Vignes, 1860. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

Photo of Burj al-Musallah and parts of the castle in the background. “Beyrouth. Forts ruinés de l'entrée.” Photo by Louis Vignes, 1860. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

Beirut’s castle once occupied a footprint of 7,120 square meters, which Antaki places at the medium-sized range. The Crusader foundation was built using a technique wherein Byzantine and Roman columns were recycled and placed across a wall of giant stone blocks. This strengthened the wall against possible invasions and against earthquakes. The deep foundations prevented people from burrowing under the walls as a means to enter.

While little of the original structure remains, one of the main findings of the excavations was a 20-by-13-meter tower.

The excavation also unearthed a large room with a pointed arched entrance, measuring 11-by- 6-by-7 meters. It was one of the halls of the castle. Adjacent to the hall is a staircase, which is currently buried by weeds. These stairs led to the upper part of the castle, which was completely demolished.

A pointed arch leading to the inside of the castle’s hall. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

A pointed arch leading to the inside of the castle’s hall. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

The castle with the remains of Ottoman homes as well as the remains of a modern concrete slab with exposed rebar. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

The archeologists also located the moat, which is not visible as it has not yet been fully excavated.

Divorced from its surroundings

The part of the castle where ships would have docked was also uncovered, something that is hard to imagine today because the castle is 140 meters inland. The reason it is difficult to see how the castle relates to its surroundings now is that much of the landscape it sits in has dramatically changed.

For one thing, it no longer borders the sea. This was a result of a massive project undertaken in 1890 to expand the Port of Beirut, which bordered the castle. Jens Hanssen, an associate professor of history at the University of Toronto who has studied the urban development of Beirut, explains that in 1878 plans were made to expand Beirut’s port to accommodate the increasing trade caused by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1863.

The idea behind the new port was also to facilitate the silk trade between the Middle East and Europe. However, the terrain was not suitable for such a plan because of rocky cliffs and shallow waters, so the engineers opted for man-made solutions, which included digging a deep basin and landfills, pommeling the rocky cliffs, and reclaiming land from the sea.

A new location was chosen for the port, stretching from Khan Antoun Bey (now the Zaha Hadid building) to the outskirts of the old Beirut near Gemmayzeh. This planned port would mow over the castle and the surrounding area through a landfill. The idea was shelved for a while but regained steam in the mid-1880s when more investors became interested in the project. A joint-stock company was established to run the port, and work commenced in 1890, led by engineer Henri Garreta. The crew began digging a basin and building a landfill for the port terminal that would receive ships. The last thing left to do was demolish the castle and the neighboring lighthouse.

Plan to expand the Port of Beirut from Khan Antoun Bey to Gemmayzeh in red shading, superimposed over Julius Loytovyd’s map of Beirut. Castle referred to as El Burj al Fanzar. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

Plan to expand the Port of Beirut from Khan Antoun Bey to Gemmayzeh in red shading, superimposed over Julius Loytovyd’s map of Beirut. Castle referred to as El Burj al Fanzar. (Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France Gallica)

Not much was done to save the castle. Hanssen noted that there was an Ottoman law at the time that protected heritage buildings, but the demolition of the castle seemed to slip through with no opposition. As he put it, “a legal mechanism existed and would have been evoked,” but it wasn’t.

He added that this was because Beiruti merchants were pressing for a new port and economic demands overrode any sentimental attachment to the buildings. Then again, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that people had any attachment to it either.

Hanssen says that while doing research on the transformation of the port, he was stunned to find nothing in the local press lamenting the destruction of the castle. This also extended to the Ottoman Imperial Archive.

Hanssen added that the only sentiment he could find towards the loss of the castle was in a book quoting one unnamed French engineer working on the project, who lamented the loss by saying “It may appear a little savage to destroy the ruins which gave Beirut’s entrance a picturesque aspect,” while noting that the locals didn’t much care for it.

As a result of the project, Beirut’s waterfront was extended and its border with the sea was enlarged. The landscape around the castle had changed and morphed into something different, alienating it from its surroundings.

Since then, modern aspects of the city have overlaid the castle, including part of Beirut’s sewage system, which cut across the site, and the remains of some of the Ottoman buildings that were built wall-to-wall with it, possibly in the 18th century. Moreover, the remains of many modern pre-Civil War buildings are notably anchored to parts of the castle, as is the case of a concrete slab with exposed rebar steel poking out.

The castle with the remains of Ottoman homes as well as the remains of a modern concrete slab with exposed rebar. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

The castle with the remains of Ottoman homes as well as the remains of a modern concrete slab with exposed rebar. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa)

Does the castle have a future?

Originally, the idea was to incorporate all these findings from all the different eras into one big archeological park.

“Everyone agreed that these had to be preserved,” said Antaki, and there were talks to this end, but they mostly led nowhere.

One idea floated was to turn the castle’s main hall into an exhibition place, but it has not been fully excavated and to do so “would be expensive to realize,” Antaki explained.

So instead of any of the grander plans, panels were erected along a small path through the remains to explain the findings. Although it is open to the public, it is unsafe for foot traffic, as there is no platform to walk on. During the mass protests that began in October 2019, some demonstrators went inside and painted graffiti on the walls of the castle.

Antaki contended that excavation of the castle needs to be completed and the ruins should be kept as is moving forward. She added that “the idea isn’t always to excavate a site exhaustively, because look at what happened at Jbeil,” which was completely excavated, preventing future archeologists from making their own discoveries. She believes it is still possible to create an archeological park at the site in Beirut.

As for Hanssen, he said, “pedagogically, you can show the world historical forces from the Crusades to the Mamluks” at play in this one monument, noting that the castle can be used to “tell a good story of appropriation of layers of history, the past is there but it gets turned upside down.”

Antaki also echoed this: “The city is defined physically and materially by the presence of the castle.”

But today the castle is barely visible because of weeds that have sprouted over it.

With all that Lebanon has experienced in the past two years, a renovation or preservation project is not on the top of any agenda, but neither are possible threats to the site’s existence.

But better awareness of the castle’s rich history can protect it from its past fate, because as Antki says: “You cannot expect … monuments to survive in Beirut.”