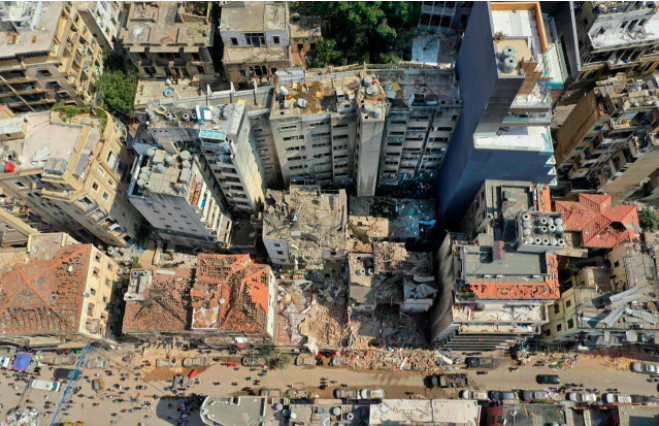

An aerial view of the damage caused by the explosion at the port of Beirut, taken on August 26, 2020, a few days after the tragedy. (Credit: AFP)

“We will never know how much funds in private donations have arrived in Lebanon and anyone who tells you otherwise is a liar,” a senior security official who has been involved in post-blast relief work told L’Orient-Le Jour.

According to him, it would be impossible to trace aid funds that poured from all over the world into Lebanon after the explosion.

The magnitude of the Beirut port blast — one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history — and the resulting widespread destruction shocked the entire world.

The scenes were devastating. A huge mushroom cloud of smoke ripped through the city. People covered in blood scattered in the wrecked streets. Thousands of injured swarmed to the destroyed hospitals. The disaster’s chilling images have gone around the world, as have the calls for donations.

The explosion dealt a heavy blow to the country that was already hit hard by an economic crisis that had plunged half of its population below the poverty line. Lebanon was dead on its knees.

Today, 80 percent of Lebanese live in poverty.

The final death toll stands at 219 dead and 7,000 injured. Some 300,000 people have lost their homes.

Aid from the international community gradually arrived via the United Nations. Meanwhile, local actors and the Lebanese diaspora were swift to mobilize efforts in great solidarity with the victims, well aware, amid deep distrust of the government that had been growing since the October 2019 uprising, that the bankrupt state would not be of any help.

The port of Beirut, seen from an apartment devastated by the August 4, 2020 explosion. (Credit: Nabil Ismail)

The port of Beirut, seen from an apartment devastated by the August 4, 2020 explosion. (Credit: Nabil Ismail)

In the aftermath of the tragedy, an army of volunteers from different areas in Lebanon, supported by various associations, took it upon themselves to clean the streets and apartment buildings of rubble and broken glass.

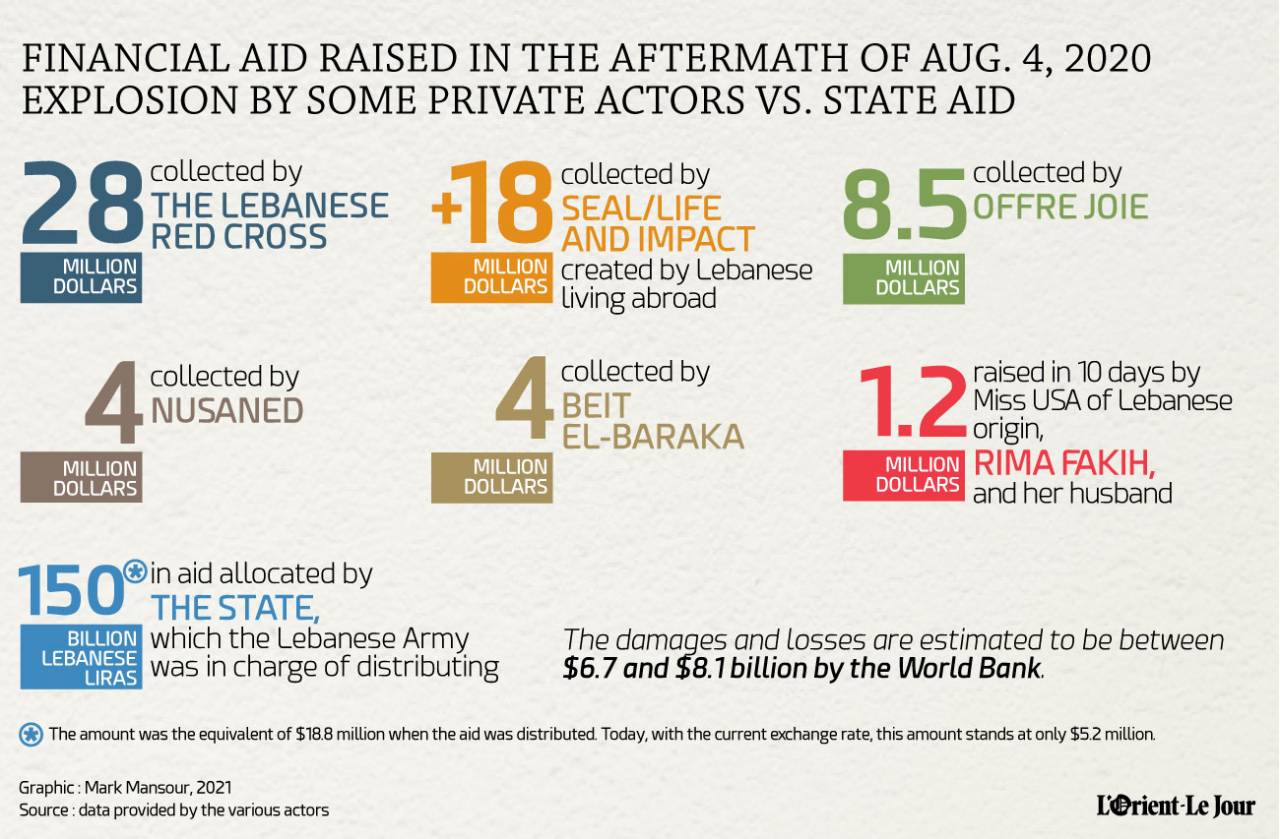

Hundreds of fundraisers were organized online to benefit the explosion victims, some of which were launched by celebrities, such as a former Miss USA of Lebanese origin Rima Fakih and her husband, who managed to raise $1.2 million in just 10 days.

The funds were generally donated to well-known and long-established associations namely the Lebanese Red Cross or Offrejoie (Joy of Living), which respectively received some $28 million and $8.5 million. Part of the funds went to organizations that emerged at the start of the economic crisis and proved their worth, such as Beit el-Baraka and Nusaned, both of which received nearly $4 million.

Online platforms such as Seal, Life and Impact Lebanon, created by the diaspora, managed to raise a total of more than $18 million.

Internet links listing the names of trusted organizations made the rounds on social media, guiding Lebanese people living abroad wishing to contribute to the aid effort. The Lebanese diaspora is estimated at eight million people, compared to a population of approximately six million Lebanese living in Lebanon.

Grassroots initiatives were also launched by local citizens who turned into real humanitarian workers, such as Basecamp and Nation Station, which also gained trust and attracted donations.

Everything was done to bypass state institutions and a political ruling class deemed corrupt and incompetent, accused of being responsible for the port explosion.

Local associations left to their own devices

The international financial aid that has been disbursed to date amounts to around $318 million, most of which came in the first four months after the explosion.

This amount pales in comparison to the large-scale destruction that affected houses, heritage buildings, schools, businesses, companies, tourist establishments and places of worship, among other properties.

The damages and losses are estimated to be between $6.7 and $8.1 billion by the World Bank.

Most of the international aid has been distributed to UN agencies, such as the World Food Program, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which usually coordinate action with their partners in the field, generally international NGOs, such as Care, Acted and Caritas, among others.

In relief and aid projects like these, the funds destined for victims are generally cut down by all the intermediate costs levied by these organizations.

For their parts, the local associations, although more active and more familiar with the local settings, hardly benefit because of their weak structures hindering them from meeting the necessary administrative requirements to be eligible for these types of funds.

Excluded from these aid mechanisms, and yet forced to compensate for the inadequate international response and the absence of the state efforts, local organizations found themselves pushed to the center stage with a great burden of responsibility on their shoulders: Returning the people affected by the blast to their homes and workplaces before the onset of winter; meeting their food, health and financial needs; and trying to save heritage buildings threatened with collapse.

All of a sudden, these local and sometimes fledgling organizations with little experience were managing funds that amounted to millions of dollars in some cases, teams of volunteers made up of hundreds of people, contracting with entrepreneurs and trying to coordinate their actions in the absence of a state structure necessary in the context of a disaster of such a scale.

To make things worse, these organizations had to operate in the midst of a full-blown financial crisis, with banking restrictions on withdrawals and a depreciating national currency that was trading at LL7,150 against the dollar on Sept.1, 2020 and fell to LL13,000 per greenback on June 1, 2021. This caused contractors to demand more money than what was accounted for.

This is not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic that halted work, home visits and field assessments for several weeks.

All these unfortunate events resulted in a string of dysfunctions, whether in terms of transparency or management, and adversely impacted the effectiveness of the humanitarian response.

An aerial view of a neighborhood devastated by the explosion, August 7, 2020. (Credit: AFP)

An aerial view of a neighborhood devastated by the explosion, August 7, 2020. (Credit: AFP)

After declaring a state of emergency, the Lebanese government delegated the army to coordinate all relief efforts and renovation work in the affected areas.

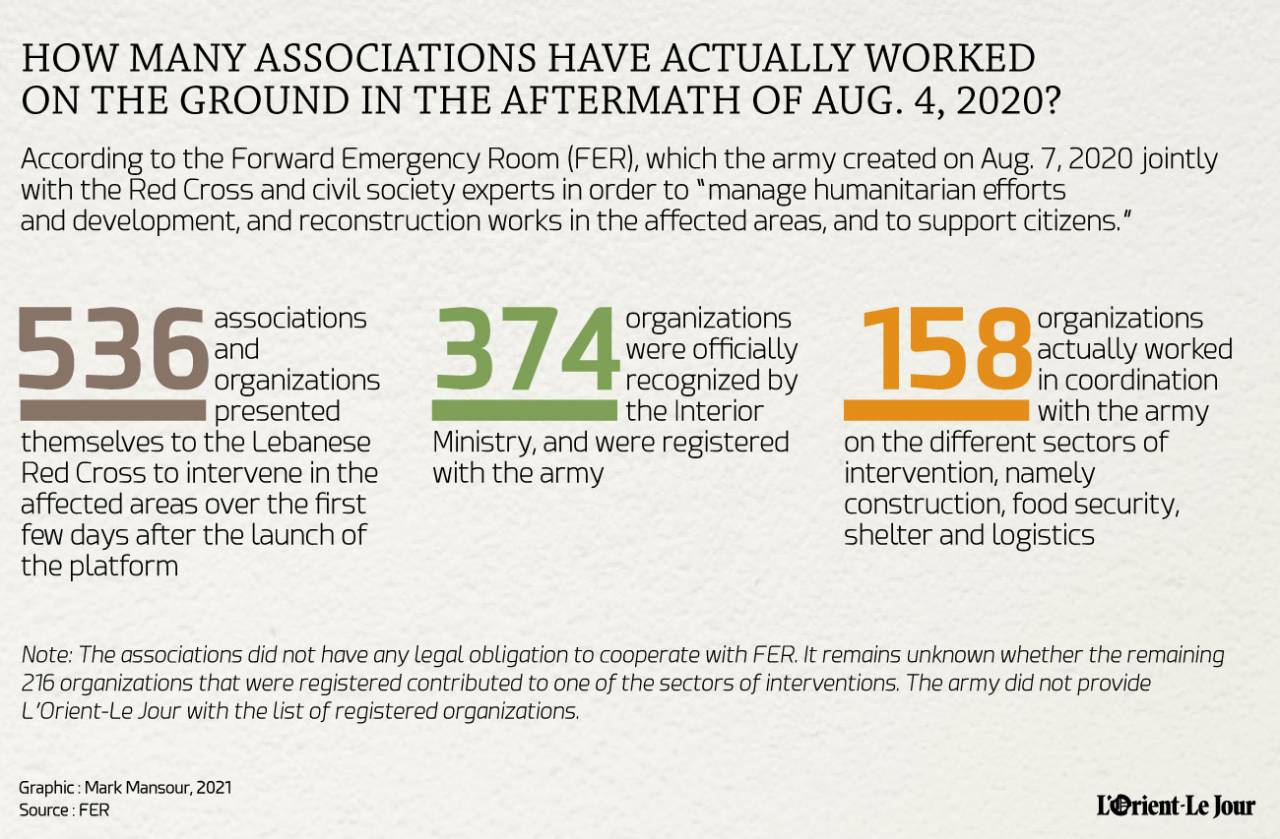

On Aug. 7, 2020, the army created the Forward Emergency Room (FER) jointly with the Lebanese Red Cross and experts from civil society, which served as an operations center in a bid to ensure coordination and visibility in the humanitarian response among the different stakeholders working in the affected areas.

In order to avoid redundancy, NGOs were invited to use a digital platform dedicated to reconstruction work, to report the areas they were assigned and the achieved progress.

The organizations, however, had no legal obligation to share their information or to cooperate with the army’s emergency room. In a climate of mistrust of Lebanon’s institutions, many chose to stay away from it.

The murky waters of NGOs

It is extremely challenging to figure out the number of associations that have actually worked on relief efforts, the amount of money each had been allocated and how these funds were put to use.

Apart from having to register with the Interior Minister to be officially recognized, these organizations have no obligation whatsoever except to hand over an annual audit that no one would ever check.

According to FER, over the first few days after the launch of the platform some 536 organizations presented themselves to the Lebanese Red Cross to intervene in the affected areas. The number then fell to 374 organizations. Having been officially recognized by the Interior Ministry, these organizations registered with the army.

“They participated in meetings with us and were supposed to keep us up to date on their progress,” Gen. Fouad Obeid, FER director since April 2021, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

But at the end of the day, only 158 organizations really worked in coordination with the army on the different sectors of intervention, namely construction, food security, shelter and logistics, including the supply of household appliances and cash assistance.

The army did not provide L’Orient-Le Jour with its list of the registered associations, which made it impossible to verify whether the rest of the organizations contributed to one of the intervention sectors.

An official who spoke on condition of anonymity estimated that around 1,000 NGOs were operating in Beirut in the first weeks in the wake of the disaster.

During this period, the residents of the affected neighborhoods reported that a large number of associations visited their apartments to assess and take photos of the damage, but they never returned.

“Did the data they collected allow them to get some money that they kept for themselves? Or was it that they just couldn’t get the funds?” a resident of an affected neighborhood in Gemmayzeh asked, as did many others.

The landscape of NGOs in Lebanon is heterogeneous, with many associations being directly or indirectly affiliated with political parties and/or religious communities.

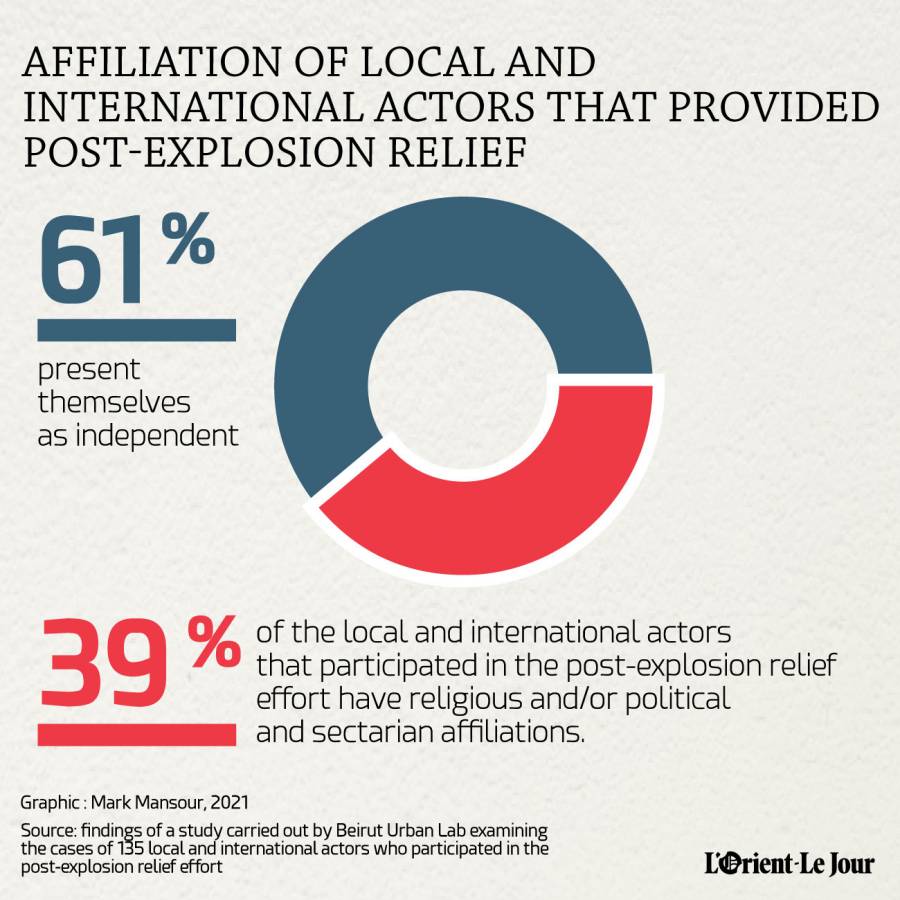

A Beirut Urban Lab study, conducted by Mona Harb with Luna Dayekh and Sophie Bloemeke, examined the cases of 135 local and international actors who participated in the post-explosion relief effort.

It appears that 39 percent of them have religious and/or political affiliations, while the remaining 61 percent define themselves as independent.

In any case, donors are free to make direct contributions to any organization they believe provides the best aid.

In Mar Mikhael, where the church is very present, the World Patriarchal Maronite Foundation has, for example, been very active.

According to city planner Mona Harb, support for religious associations may have been fueled by fears after the explosion that residents might be evicted from their homes for real estate investment projects that could alter the sectarian identity of the predominantly Christian areas.

Ground Zero, chaired by May Chidiac and affiliated with the Lebanese Forces, a Christian party, is also one of the most active organizations in these areas, according to residents.

These kinds of organizations, however, are likely to base aid distribution on certain profiles instead of offering inclusive aid.

A resident of Rmeil, whose apartment has been completely renovated by the LF, claimed that he was directly selected by the party because his name figures on its list of supporters.

The Armenian Tashnag Party is also known to have been most active within the Armenian community, which is also very represented in these affected neighborhoods.

“We know very well that the associations with political affiliations will go to their supporters! That’s how it worked here,” a local politician said on condition of anonymity.

The ambiguity surrounding NGO finances is another obstacle to fully evaluating how the donations they received were used.

In Lebanon, banking secrecy prevents any authority from verifying the accounts of an association. It is therefore impossible to know whether a part of the aid was used outside the framework of humanitarian effort.

Donors also bear some of the responsibility for allocating funds to organizations that do not implement mechanisms for fund traceability and transparency.

Contacted by L’Orient-Le Jour, Ground Zero claimed not to be able to estimate the amount in donations they received for their action in Beirut. The World Patriarchal Maronite Foundation, for its part, did not respond to requests for comment.

The diaspora’s active role in creating a model of transparency

Shocked by the tragedy that struck Beirut, some members of the Lebanese community abroad played a crucial role in a bid to ensure that aid reached the affected population.

Impact Lebanon is one the initiatives launched by the diaspora and that stood out in putting forth high standards for transparency tools (see box below).

The platform chose to make its donations, to the tune of $9.2 million, to a total of 18 handpicked NGOs which received between $47,000 and $1.55 million depending on their projects, such as Beit el-Baraka, House of Christmas and Live Love Beirut, among other organizations.

A positive competition for transparency emerged among local NGOs which enabled donors to follow up on how their financial contributions were utilized. For instance, Beit el-Baraka distinguished itself by developing a tracking tool that gives the donor real-time access to the unit they financed, with an overview of every step taken and a copy of the original invoices.

Paradoxically, this demanding process of sorting out NGOs enabled some fledgling organizations to be involved in the relief work.

Bebw’Shebbek (Arabic for “Door and Window”) is among these initiatives that emerged in the explosion’s aftermath and decided to shut down when their funds ran out.

“My partner and I know all the architects and interior designers in the country. We couldn’t stand idly by. To take the pressure off the NGOs, we decided to focus on repairing windows and doors quickly before winter,” Mariana Wehbe, one of the co-founders, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

Bebw’Shebbek raised $1.2 million and gathered a total of 200 volunteers to manage the first months, time enough to form a small team of 25 employees.

Most NGOs had to use part of the donations they received to pay their teams’ salaries. A small organization like Baytna Baytak reports having paid, during the peak of its activities, 60 people between $300 and $2,000 depending on their position.

To date, 87 percent of funds raised by Impact Lebanon have been disbursed to NGO accounts, leaving it with a cash total of $1.5 million.

Cash assistance

In any country with a functioning government, all victims of a disaster of this magnitude would have received financial compensation.

Marred by corruption and mismanagement, the Lebanese government has been unable to pay off this debt to its people.

A sum of LL150 billion was allocated by the government for the explosion victims. The amount was the equivalent of $18.8 million when the aid was distributed. Today, however, with the current exchange rate, this amount stands at only $5.2 million.

The army was responsible for distributing cash based on damage assessments it carried out in the affected neighborhoods with the help of 500 volunteer engineers.

This amount, however, proved to be grossly insufficient, and dried up at the very beginning of February 2021, prompting the army to halt all cash assistance.

This is not to mention that those who had benefited from renovation work carried out by an NGO were not compensated in cash.

“Our priority was to allow people to be able to return home. We had to focus on households that hadn't yet received help because we did not have enough money for everyone. But that does not mean that the others were not eligible,” the FER director explained, adding that the government had pledged to allocate another LL50 billion that has yet to be unblocked.

Among the largest recipients of private donations, the Lebanese Red Cross has also provided cash assistance to the victims.

The organization, which inspires confidence in donors, received some $28 million, i.e., $10 million more than the amount allocated by the state, knowing that the latter was distributed in Lebanese lira.

“It was the first time we received so much money directly,” Nabih Jabr, the organization’s deputy secretary-general, said.

Eighty percent of these funds were distributed to households, while the remaining 20 percent helped finance all COVID-19 costs and the running of the Red Cross’ blood bank.

Some $24 million (including other donations, conditional this time, allocated by the French and the British Red Cross) were dedicated to cash assistance to 10,800 households selected according to vulnerability criteria in three affected areas.

“We opted for unconditional financial assistance which preserves the beneficiaries’ dignity and freedom. They know their needs better than anyone else,” Jabr said.

The beneficiaries received $300 per month for seven consecutive months, which helped them withstand the consequences of the collapse of the local currency.

The Lebanese Red Cross distributed the funds via withdrawal cards issued by the Banque Libano-Française which, at the time of the explosion, was the only bank to quickly agree to transfer funds to recipients in US dollars.

The feedback reflects the state’s inaction

According to the FER-run digital platform, the NGOs that joined the reconstruction efforts reported having spent up to $25.716 million and LL767 million on the destroyed units that they were in charge of.

Those among them who chose to make cash payments reported to the military having provided $28.111 million ($24 million from the Red Cross) and LL12.620 billion in aid. The military was unable to provide the amount the NGOs spent on other forms of aid such as health services or food aid.

However, one must be very careful when considering all these figures, knowing that they are based on the associations’ good faith. No invoice or proof confirming how the money was spent has been indexed on this platform.

In addition, these amounts were provided on the organizations’ own initiative. Many have not shared this type of information, knowing that they did not have to.

According to the army, more than 50 percent of households have not received the needed assistance that would enable them to return to their homes.

In early 2022, the FER is expected to finalize a reassessment, identifying those homes that were left behind and inspecting the units that NGOs reported having repaired.

“While working on the ground, we have been faced with the ire of the residents who have been deprived of assistance,” Gen. Obeid, FER commander, said.

Beneficiary targeting is also a sensitive point in the feedback. In its humanitarian response analysis (published on its website), the Lebanese Red Cross found that some mistakes were made due to the quantity and speed of the assessments carried out during the first few weeks, leading to well-off households being classified as eligible for aid.

There was also some duplication, with two members of the same household receiving assistance. “These mistakes were rectified in the early months. Overall, our targeting was found to be more than 90 percent successful,” Nabih Jabr said.

On the contrary, people who have been heavily affected by the economic crisis tried to benefit from the aid that was intended for the victims. The NGOs reported being shocked by the staggering number of people in need across the country.

The Red Cross indicated in its study that 1 percent of recipients of its cash assistance were fraudsters. This type of problem is generally reported by many NGOs that stepped in amid chaos and the pressure to identify needs as quickly as possible.

Cases of repair work in wealthy households at a time when budgets were very tight were also discovered.

“I visited some very luxurious apartments that NGOs had included in their list of vulnerable beneficiaries. They are rich people, and yet there was work done in their apartments with very expensive materials! Why have these NGOs used donations for apartments that do not deserve them?” engineer Nadine Sinno of Frontline Engineers said. Her organization has been commissioned by donors to carry out monitoring and compliance missions in homes, businesses and heritage buildings.

She also pointed out the poor quality of much of the work done (paint peeling off after three months, incomplete windows, etc.) which forced the victims to pay out of their own pocket for new repairs.

Despite corruption cases, these impairments are ostensibly correlated to the absence of a central body regulating humanitarian response.

This role, which is normally shouldered by the state, has been left to NGOs, on which civil society and donors have placed exaggerated hopes for efficiency and transparency.

“Admittedly, there were inefficiencies, but we did what we were able to do amid a political vacuum. No country in the world became developed through organizations. We certainly do not want to disseminate this model of ‘the Republic of NGOs’ that we have seen in Haiti,” Maya Murad, a 26-year-old management consultant and volunteer at Impact, said.

“I’ve never thought that I would be doing all that; This angers me, because it's not our role. But we assumed it,” she said.

Impact Lebanon: an example of good practices

Impact Lebanon, which a group of Lebanese in London founded after the Thawra, is a platform that today has brought together members of the diaspora from around the world. Although presented as apolitical, it has been working to promote transparency and efficiency in Lebanese governance since 2019.

Its reputation resulted in the platform attracting 171,000 private donors when it launched a fundraiser to revive Beirut after the explosion, and raised $9.2 million in total. “This amount was not anticipated at all. We thought we would collect a maximum of 5000 pounds!” Alexandra Mouracadé, audit and project management expert, and volunteer in the Beirut relief effort for a year, said.

It is a huge sum, similar to the pressure to put it to good use. Sixty-six people, each armed with professional skills (finance, marketing, management, etc.), volunteered to create a method to allocate these funds and select the associations who would benefit.

“In the beginning, we conducted a great deal of fieldwork to assess the needs because it was a total mess. Then we submitted our agenda to the local NGOs who applied, giving them instructions about the six affected sectors that we established, with particular emphasis on rehabilitation. The NGOs had a deadline to send us their proposal, then we selected them according to criteria and value, vetted by 3QA, an audit firm with whom we worked,” Maya Murad, management consultant trained at MIT and a volunteer for Impact, said.

3QA is a third sector quality assurance firm that operates at the request of donors. "We have developed a framework, based on international criteria, which allows the donor to ‘monitor’ the NGOs they support," Tara Hermez, co-founder of 3QA, said.

3QA intervened at several stages of the Impact process. First by performing due diligence on the NGOs that applied (structure, finances, accounts, affiliation, etc.). “We red-flagged doubtful or risky elements, but the final decision was that of the donor,” Hermez added.

The company subsequently evaluated the NGOs’ proposals, requiring readjustments and clarifications of their proposals, before they were made to Impact. In the end, 18 out of 150 associations were selected.

“It's an overly complicated and strict process. Many NGOs gave up along the way. Many were ruled out due to some doubts we had about them. We were also obliged to reject some projects due to their multiplicity and limited funds,” Murad said.

The funds were not disbursed all at once, but as the announced objectives progressed, with regular field and financial vetting at several stages.

However, this disbursement method, which meets a transparency requirement on the part of platforms like Impact, Life and Seal (A US-based diaspora network), continues to be an exception in Lebanon.

“In the end, we had limited access to the funds that landed in Lebanon. Many donors did not set solid conditions for the NGOs to meet, and large amounts were disbursed in the absence of any control,” Hermez said.

“Effective giving is a model that needs to be broadly spread, so that donors do not contribute more destruction to the country than aid.”

This article was produced in partnership with the Samir Kassir Foundation.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.