Lebanese officials count ballots at a polling station in Beirut on May 6, 2018. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

While the vast majority of the Lebanese impatiently await the holding of the 2022 parliamentary elections, Lebanon’s perennial uncertainty continues to hover over the proper holding of the election on the scheduled date.

All citizens and observers remain fixed on the Constitutional Council, which must take, by mid-December, a decision on the appeal presented by the Free Patriotic Movement for the invalidation of electoral law amendments passed by Parliament. Among the issues at stake are the advancement of the elections from May 8 to March 27 and the voting modalities of expatriate citizens (with the suspension of the specific district of six deputies which was devolved to them by the electoral law of 2017).

This last point is particularly crucial for the forces at play given the vigorous campaign led by opposition parties and civil society NGOs to mobilize a Lebanese diaspora that is increasingly sensitive to the political fate of its country of origin following the October 2019 protest movement, the multidimensional crisis that beleaguers the country, and the explosion in the port of Beirut.

With undeniable success, last Thursday, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that 230,466 expatriates will be able to vote in the upcoming legislative elections, out of 244,442 registered as of November 20 and a larger contingent of 800-900,000 non-residents of voting age. This figure exceeds the most optimistic initial forecasts — a barometer distributed by the NGO Sawti on social networks had for example set a target of 150,000 registered voters, updating it to 200,000. More importantly, this represents almost three times the number of registered expatriates (83,000) in the previous election in 2018, when expatriates were allowed to vote for the first time, and an increase of about 7.9 percent over the total number of registered voters in 2018.

First step

But before taking a premature victory lap, we need to know the profile of those who have registered to vote. Are they Lebanese who have been expatriated for years and only now have woken up with a desire to save their homeland? In this case, the increased diaspora registration could have a significant impact on the overall result and represents real hope for anti-establishment forces.

Hope not tempered by critical thinking, however, amounts to very little. The establishment parties surely did not sit back and watch tens of thousands of expats who hate them register to vote without mounting a counter-effort to balance the scale with their own loyalists. So at least some of the excess expats who registered will reflect traditional voting patterns. Also, if the additional registrations correspond to people who left the country in the past two years of crisis, then the voter pool might not change so much when compared to 2018. We may have merely moved around the same anti-establishment voices. Though we don’t know the exact profile of those who left the country, anecdotally we can surmise that the best educated and financially capable citizens already possessing foreign passports probably tend toward anti-regime sentiments.

Still, the increase in voter registration changes the game at least a little. But registration is merely the first step, and it was a relatively easy one, requiring only an online login with a Lebanese passport or ID; proof of residence outside Lebanon. Then comes step two: how many of those now registered will actually turn up to physically vote? It’s a much tougher barrier to cross than simply registering, because it requires time, physical effort, and travel costs, as expatriate voting can only take place in a Lebanese embassy or consulate, of which there were only 126 worldwide in 2018. The result from that year: only 56 percent of those expats registered followed through and voted.

Then of course, for those anti-establishment forces hoping to capitalize on this pool of expatriate voters, comes step three: to what extent will those voters who actually do take the time to physically get to a consulate consolidate their voices behind one opposition list in each district?

Modeling the hopes

Let’s model what impact these “new” 147,000 voters might have on the election result. In order to do this, we will use the detailed results of 2018 as a basis for calculation, with several implicit assumptions (which will we question later): that those who turned out in 2018 will vote in 2022 (and according to district-by-district turnout that matches the previous election), that the establishment voters remain loyal to their parties, that those who voted for opposition lists in each district will do so again, and that the expat registrations are proportionally distributed across all districts.

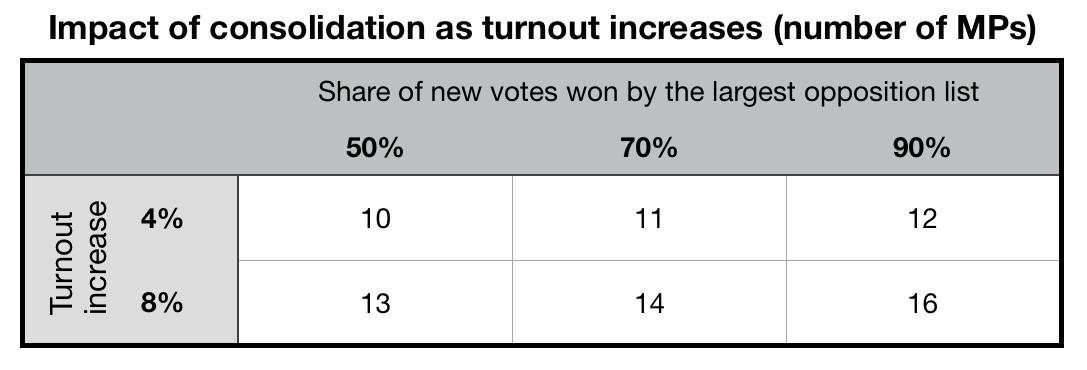

In a best-case scenario, in which all 147,000 “new” expat voters have never voted before, and all of them actually vote in person, it will yield an 8 percent increase in voter turnout. If 90 percent of these votes consolidate behind one opposition list, it will produce 16 anti-regime MPs.

If however, 20,000 of those “new’ 147,000 are voters loyal to traditional parties, and 20,000 are sympathetic to the opposition but had voted in the country during the last election, we are left with only 107,000 “new” voters. If this time, expat turnout increases to 70 percent from 56 percent, that leaves only 75,000 “new” anti-regime voters, or a 4 percent increase in overall voter turnout. In this case, it will be enough to produce 10 anti-regime MPs, even if only half of them vote for a single opposition list.

This 2022 election projection model was created by George Ajjan using 2018 election results and turnout statistics on a district-by-district basis.

Based upon these calculations, getting to 10-12 MPs on the basis of expats alone should not be too difficult, unless ego battles produce a confusing number of opposition lists. The recent Beirut Bar Association elections are a cautionary tale in this regard. Rivalry between personalities and contests of ideological purity do not augur well for changing the composition of parliament. Avoid them at all costs.

Overall, the focus on expatriates will probably yield several more independents than currently sit in parliament, but the impact falls short of the best hopes of opposition forces. This is why focusing so heavily on expat registration and mounting practically no local campaign before the end of November was an unwise strategy. Yes, expats can vote, and because they are sending money to their families back home, their voices also have outsize influence on voter preferences. More importantly, they are an obvious source of potential campaign funds to any eventual candidates.

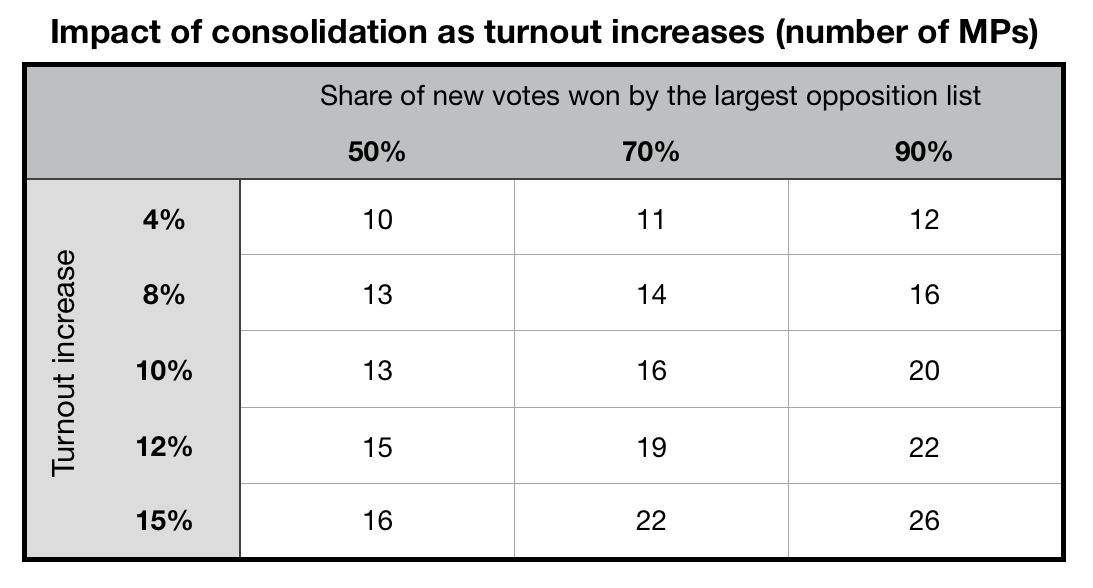

But expats are not enough. To dramatically change the makeup of parliament, anti-establishment forces need to turn out more voters inside the country. This will require lists populated by respected and credible individuals who are well-known and appreciated in their districts, who have the capacity to inspire ordinary citizens that change is possible and that it’s worth going to vote this time. If they manage that, here is what happens:

This 2022 election projection model was created by George Ajjan using 2018 election results and turnout statistics on a district-by-district basis.

To reach more than 20 MPs, 100-120,000 local Lebanese who haven’t voted before would need to turn out, in addition to the new expat voters. A well-run campaign in Beirut would be the best place to start, as the turnout in Beirut District 1 in 2018 was an anemic 33.2 percent, more than two standard deviations away from the countrywide turnout of 49.7 percent. In Beirut 2, the situation was not much better, as turnout reached only 41.8 percent. These were the two lowest in the whole country in 2018, followed closely by Tripoli at 43.3 percent.

On the other hand, there are counter-examples of districts that had abnormally high turnout, which need to be studied to understand how to replicate this trend across the country. For example, Baalback/Hermel saw turnout of 60.3 percent, the second highest in the country in 2018, while Jbeil/Keserwan delivered an eye-popping 66.6 percent, also more than two standard deviations away from the mean.

Aggressive strategies

This numerical model also illustrates dramatically how crucial it will be to avoid internecine battles between opposition lists. The more turnout increases, the greater the payout for consolidating the anti-establishment vote behind a single list. For example, if turnout increases 10 percent and half of those new voters consolidate behind one list, 13 MPs result. But if almost all of them consolidate, the result is 20 MPs. If the campaign is exceptionally strong and manages to increase turnout by as much as 15 percent, it will produce 16 MPs if half of those new voters stick to one list. But if they fully vote as a bloc, it produces 26 MPs. The impact of consolidation cannot be overstated.

Bottom line: it is neither impossible, nor too late, to mount a proper, integrated campaign that exploits the assumptions that limit this model. First, as demonstrated above, it is crucial to have strong candidates who can relate to disaffected people in villages. They, not the elites of Beirut, are the heart and soul of the country and ultimately they will decide who runs it. Secondly, an overtly negative campaign against the establishment parties must be mounted, not to convince new people to vote, but rather to suppress turnout of traditional voters, so that such people in other regions of the country will vote as anemically as those in Beirut did in 2018. Finally, the most difficult task is to convince voters who previously supported the establishment to abandon them and vote for an opposition list. Perceived momentum toward the end of the campaign will largely govern this phenomenon.

All of this necessitates much, much more strategy than organizing an online voter registration drive for expats and will require discipline, organization, and determination not yet witnessed among the anti-establishment forces. If they rise to the challenge, however, their goal of 22-23 MPs is within reach. While this result falls far short of a majority of 65 seats, it would break through a wall of political stagnation that has blocked progress for decades. On this basis alone, it would be cause for celebration. Of course, one can still hope for an even more significant change.

George Ajjan is an international political strategist and a former Republican candidate in the 2004 US House of Representatives elections.