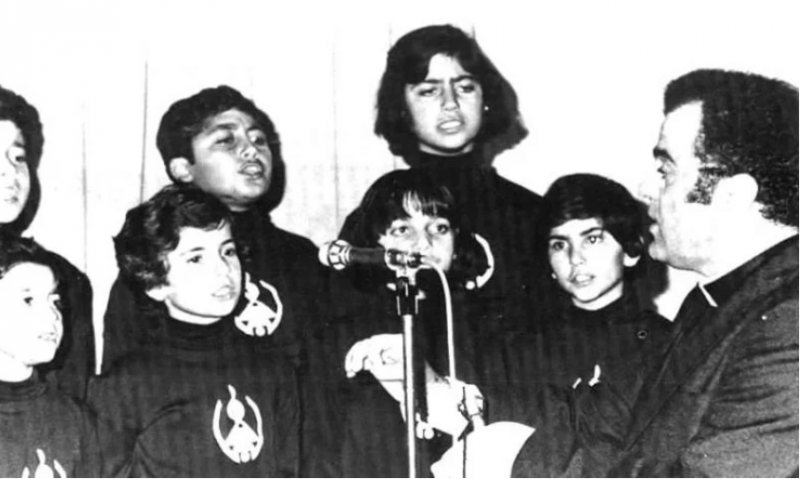

Mansour Labaky (here in 1978) wanted to launch a choir across Lebanon, like the Little Singers at the Cross of Wood. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archives)

The sky was cloud-covered over the mountain of Broumana. At the top of a hill lined with pine trees stood an austere white building.

At the reception desk, a woman behind the counter picked up the receiver.

“Hello? May God bless you, Monseigneur, some journalists are here to see you,” she said. Her face suddenly changed. “Oh, he’s not there?” she muttered, nodding her head.

“He doesn’t come here often. He has many institutions to manage,” the woman added.

Whether or not Mansour Labaky was actually on the premises of the Sisters of the Cross Convent in Broumana that day remains a mystery.

Since the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith found him guilty in 2013 of sexual abuse of three minors over a period spanning from 1976 to 1997, Labaky has been taking refuge in this almost deserted place, condemned to a life of prayer and penance, far from any minor, and deprived of his ecclesiastical office.

Eight years after having been convicted by the Vatican, the priest found himself this time facing criminal courts in France.

On Monday, the priest was sentenced in absentia to 15 years in prison on charges of rape and sexual assault of minors by the criminal court of Calvados in Caen, Normandy. Labaky, who is taking refuge in Lebanon, was not present at the court hearing. An international arrest warrant was issued against him in April 2016, but Lebanon does not extradite its own nationals.

It all allegedly began in France in the Notre-Dame-Enfants du Liban children’s home, which welcomed Lebanese orphans and was established by Labaky in 1990. In 1998, the orphanage closed its doors.

Since the court of Caen launched an investigation against him in 2013, Labaky has never set foot on French territory again.

In 2017, Lebanon refused to extradite him despite an arrest warrant issued against him via Interpol a year earlier.

At least 40 victims are listed in the file, “but for most of them, their claims are time-barred. Lebanese victims are surely many more, but they cannot speak up as long as Labaky has so much power in Lebanon,” Solange Doumic, the lawyer of three plaintiffs, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

The priest, who continues to protest his innocence, still retains a certain aura of respect in his home country. Father Mansour is inscribed in the collective memory as the cantor of the Maronite Church and the savior of the civil war orphans.

A prolific music composer and writer, his liturgy has marked several generations. For a decade, Labaky was able to count on the support of a portion of the Christian community, all the way to its most powerful branches.

In response to the accusations, the priest cites a conspiracy concocted against him. His Lebanese lawyer, Antoin Akl, speaks of an inheritance case that had gone wrong, triggering the ire of some of the plaintiffs, but also of a “Zionist” cabal targeting the priest who was able to convert an “originally Jewish academic” to Christianity.

“One day, I will make the Mass sing”

Labaky, born in Baabdat in 1940, was ordained on March 26, 1966. Lebanon was at the pinnacle of its golden years, and the young cleric did not lack ambition.

He was then in charge of spiritual direction at the Patriarchal Seminary in Ghazir. It was there that Antoine Saad, former secretary general of the Christian Télé Lumière television channel, and current secretary general of the La Sagesse University, met Labaky for the first time. Saad was 12 years old.

“He was our music teacher. He raised me, like hundreds of other young people. Not once have I heard someone complain about an inappropriate word or gesture by him,” Saad said, defending the innocence of his longtime friend.

“Someone as busy as he is, who knows many people in high positions here and elsewhere, does not have time to engage in the things he’s being accused of,” he added.

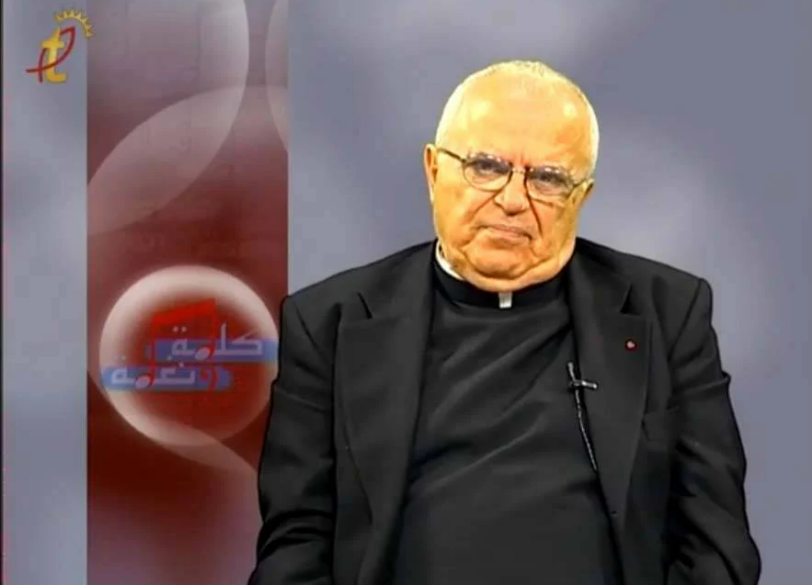

Mansour Labaky during an appearance on Télé Lumière. (Video capture)

Mansour Labaky during an appearance on Télé Lumière. (Video capture)

In the early 1970’s, Labaky left Lebanon for the United States, where he began translating liturgical melodies from Syriac to English.

“One day, I will make the Mass sing,” Labaky once said, presenting himself as the reformer of the Maronite liturgy.

“Lebanon has its own father Duval (a French Jesuit singer and songwriter), with a few small differences. He does not hop from one stage to another, or from city to city. He prefers television appearances and 45 rpm vinyl records, and instead of the guitar, he, of course, has an ‘oud,’” reads a L’Orient-Le Jour article from the year 1971.

Labaky, a workaholic, soon gained fame. He was known within family homes and religious congregations and had a string of aficionados. The Maronite Patriarch Bechara al-Rai, who at the time was much less known to the public, is a close friend of Labaky.

“He was someone who liked to be the center of attention. If his name was mentioned in an article or if he made an appearance on television, it was always the talk of the clan,” Celeste Akiki, Labaky’s niece, said.

She has been living in the US for years and was one of the few Lebanese women to publicly accuse him of abusing her when she was underage. It took her years to speak out and to extricate herself from what she calls “hell.”

Akiki was only eight years old when her uncle told her that “she and he would make a great couple,” she said.

“‘You are my favorite niece. You are sensitive, funny, intelligent. You would be the perfect wife for me,’ he used to whisper to me,” she added. This seemingly innocuous conversation marked a turning point in Labaky’s relation with his niece.

“In reality, he was preparing his prey by isolating her, and he succeeded,” Akiki said.

In 1975, the war broke out and Akiki’s father died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage. Soon afterward, Labaky was quick to present himself as his niece’s father figure and spiritual guide.

It was then when he started to sexually assault her. She was 14. He was 22 years her senior. He used to take advantage of Confession time to lock himself up with her in the master bedroom, she said.

“I remember that at some point a ‘no’ exploded in my head, but it did not come out. I was too scared,” Akiki said. Her uncle made sure to have her ostracized from the family. It was impossible for her to reveal anything. Who would have believed her?

“You are talking about Mansour Labaky, the idol of the family, who was placed on a pedestal throughout the country,” she said.

Children’s choir

It was January 1976. Labaky was then the parish priest of Damour and witnessed firsthand the Palestinian factions’ attack on the town, which left hundreds of dead.

The survivors gathered in his church as the village was surrounded and all help seemed impossible. Labaky prayed and called on the townspeople to “forgive and offer their lives for the peace in the world.”

Everyone responded with a song of faith and love. The inhabitants managed to escape by the sea, piling up in boats under the freezing rain.

The episode made him a hero and allowed him to further assume this role, prompting him to found a children's home to help orphans of all faiths.

Labaky also had in mind to launch a choir across the country, in the style of the The Little Singers of Paris.

To finance his plans, the priest surrounded himself with influential and wealthy people across the world.

Commissioned by the Maronite patriarchate, he was appointed parish priest of Roumieh in 1978, and held dozens of conferences in churches and cultural, religious and university centers.

Marilene Ghanem, now 51, met him for the first time in December 1984, when she came with her 8th grade class to interview him. The young girls were immediately won over by the charismatic priest.

“Having music in church was new to us, very modern,” Ghanem recalled.

For the Confession, the priest grabbed a chair and prie-dieu for all to see.

Ghanem was a 14-year-old adolescent and the daughter of divorced parents, something that was frowned upon in society at the time. She was going through a period of turmoil and carrying the heavy guilt of having been molested by a female cousin when she was seven.

Ghanem immediately confessed to Labaky, who had inspired her confidence. “With this face of yours, if I were your relative, I would have done the same,” the priest replied, promising to spend a day at her house.

“Come on my dear, don’t you know who Mansour Labaky is? Of course, he’s not coming,” Ghanem’s grandmother, with whom she used to live, told her back then.

A week later, he showed up at their front door.

“He came to help me with ‘my spiritual journey,’ while I couldn't care less about religion. I walked him back to his car and that’s when he kissed me on the mouth. I didn’t understand. I thought it was my fault that I had turned my head the wrong way. But when we met again, he told me he did it on purpose. And that’s when he did what he wanted to do,” Ghanem told the story from Italy, where she has been living for several years.

She added that Labaky came back to see her several times. During their meetings, he used to ask her to give him oral sex. She was repulsed but wanted to make him happy. He made her believe that she was the woman of his life.

“During the act, he used to tell me that I was his ‘Mary Magdalene,’ and that with me he ‘experienced sin and forgiveness,’” Ghanem recounted.

This “spiritual-manipulative language” was his way around several other alleged victims, who testified in Monday’s court session in Caen.

Labaky ended up disappearing abruptly from Ghanem’s life. He was caught up in his plan to establish an orphanage in France.

“He boasted about going to the Moulin Rouge, but always with his rosary, or to the casino with a French bishop friend,” she said.

Ghanem, a teenager at the time, was totally in the priest’s grip. She had now become the “rejected mistress,” which sunk her into depression. She started failing her classes, after having been an outstanding student. Her family, to whom she did not utter a word about the matter, did not understand what had gotten into her. Ghanem finally took vows as a nun, for she did not have a better option.

Not the “typical priest”

The end of the 1980s marked a new success in the life of the Lebanese priest, whose humanitarian actions were lauded and musical and literary works awarded, especially in France.

“Sexual predators are often well-known figures who have a knack for influencing the public in order to get their own way. He was not someone insignificant, he had connections everywhere,” a Lebanese priest, who, as a child, used to sing songs written by Labaky in his hometown’s church, said on condition of anonymity.

After having charmed the crowd, Labaky wanted to play a political card.

“I would like to see a miracle happening in my country, so that it would be possible for all the 17 sects to survive and to coexist,” Labaky said in Paris in October 1988, during a conference organized for the release of his book Mon vagabond de la Lune.

He even called for an international conference for Lebanon. “After all, America is fighting hard to save three whales,” he said.

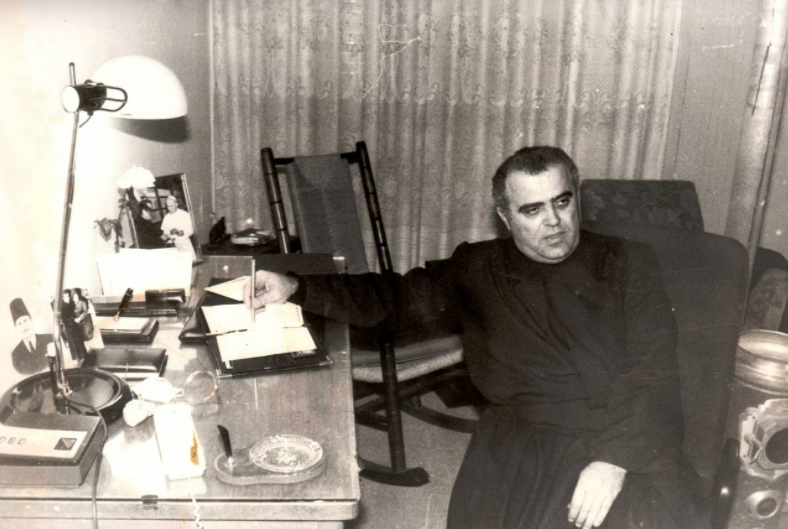

Labaky pictured at his desk. (Credit: OLJ archive photo)

Labaky pictured at his desk. (Credit: OLJ archive photo)

He opened up in a column in L’Orient-Le Jour in 1999, saying, “I could not limit myself to just being a singing priest, an author, or the ‘typical priest’ any longer. Lebanon needs action.”

In the French capital, he founded the spiritual movement Lo Tedhal (“do not be afraid,” in Syriac). The support he had within French Catholic circles enabled him to open the Foyer Sainte-Marie-Enfants-du-Liban orphanage in 1990 in Douvres-la Délivrande, in Calvados, where Lebanese Christian and Muslim, and some French, orphans were enrolled for the school year.

“He had the aura of the poet, the aura of a priest who offered himself to God. There was a war in Lebanon; Lebanon is very important to France; the people in France loved Lebanese children and were fascinated by their savior,” said Doumic.

It was in this orphanage that he allegedly raped, according to the prosecution, a 13-year old French girl, MD, who was sent there when her family was going through difficult times, as well as two Lebanese orphan girls who were sent to France when they were ages seven and 11.

“His manipulative character enabled him to use all these different auras to keep under his influence these children who couldn’t complain to anyone,” the lawyer added. The lawyer quoted some of the French victims as saying that when Father Labaky kissed them on the mouth and they took offence at it, he tirelessly reiterated the same reply: “You Westerners are too uptight; we are not like that in the East. Relax, Christ is love.”

In 2011, After several people reported the incidents that had occurred in France, the-then Ordinary for Eastern Rite Catholics resident in France, Cardinal André Vingt-Trois, opened an investigation at the apostolic nuncio’s request, before referring the case to the Parisian ecclesiastical court.

Ghanem, who had left the convent in the meantime, learned in 2012 that she is not the only one who was preyed upon by Labaky and decided to press charges. She had left no stone unturned for years in her quest for justice, to the point of calling the Vatican several times a day to follow up on every new development in the case. Akiki filed a complaint as well.

“When he founded his orphanage in Caen, he warned everyone that I was crazy, out of fear that I would disclose everything, saying ‘If my niece calls, hang up on her.’ This is what set the French officials, who searched for me years later, thinking,” Akiki says.

Labaky was heard twice before the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the Vatican in March 2012, which found him guilty in a decree issued on April 23, 2012. Rome dismissed his appeal on June 19, 2013.

“He was tried without being able to defend himself. He was only allowed one hour to read the 206-page accusation report in the presence of guards,” his lawyer Akl said.

“He was only left with oxygen”

When the verdict was announced, Akiki was warned that the statute of limitations has been lifted in her case due to the gravity of the facts, which amounted to incest.

“I recalled the whole period when the abuse started. And I wanted to put it in a box and forget about it. Even if he is convicted, nothing will restore what was lost. The innocence of children is sacred,” Akiki said.

The Congregation’s ruling barred Father Labaky from attending public masses, hearing confessions, spiritual support, public activity and speaking to the media, or being in contact with the victims.

“Every possible penalty was inflicted upon him. He was only left with oxygen!” his Lebanese lawyer said. The Vatican’s conviction was met with a backlash in the Lebanese media, which pleaded the clergy’s “innocence.”

“Two days after the ruling’s announcement, he arrived at Theater Monnot in Beirut to attend a play performed by children, where he was greeted like a star in a hall full of children. This proves that he couldn't care less. I was there with my daughters, and I saw red, but I could not make a scene,” an eyewitness said.

While Labaky did not completely disappear from public life, he did not make any media appearances, especially Télé Lumière TV shows where he used to appear regularly.

“A lot of projects and new songs are put on hold, but we cannot violate the Vatican’s decision. We hope that they take the decision to allow him to reappear,” Saad added.

Between 2013 and 2016, the priest’s supporters launched a campaign, thumbing their nose at the Vatican’s ruling. On television, the radio or in the newspapers, public figures and ecclesiastes came in succession to plead his cause.

Mother Superior General Daniella Harrouk spoke to Télé Lumière in October 2013 on behalf of all women and girls of the Saints-Cœurs schools to protest the “Monsignor’s innocence.”

“I was incensed. I am a girl of the Saints-Cœurs, and Labaky used to make me go out of the classroom to give him oral sex, in a room facing the principal’s office without her knowledge,” Ghanem said.

In a bid to stifle the scandal, Labaky’s supporters did not hesitate to drag the alleged victims’ names through the mud. His lawyer, Akl, fired a barrage at all the accusers and filed a complaint in 2014, in particular against Bishop Luis Ladaria, then number two in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Peter Germanos, the case’s investigative judge, dismissed the case without interrogating the defendants, claiming that he lacked jurisdiction over a case concerning the Catholic Church.

“Labaky couldn’t have done what he did in Lebanon if it weren’t for this culture of worshipping powerful people. Because impunity reigns, he allowed himself to attack the victims instead of paying for his mistake,” Nizar Saghieh, Lebanese lawyer for Akiki and Ghanem, said.

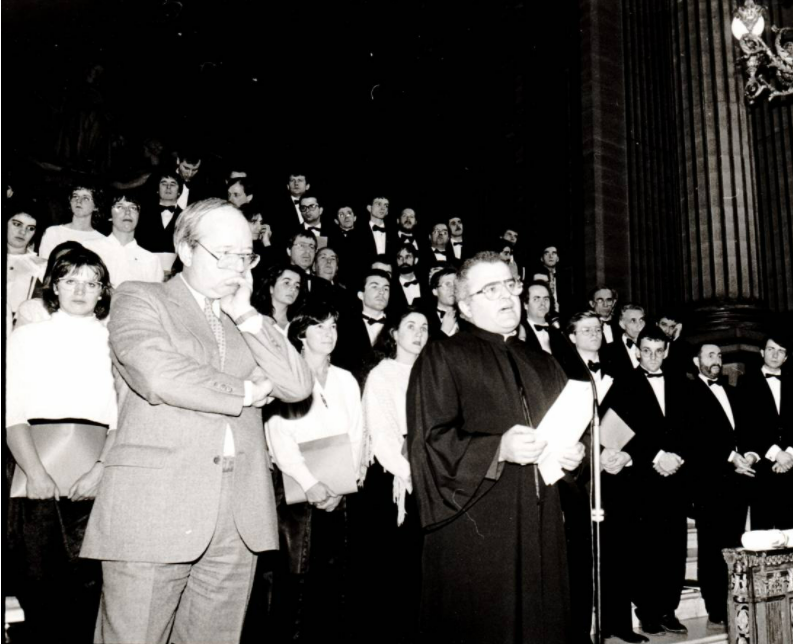

Mansour Labaky, in the Madeleine church, next to Bernard Porte, in 1987. (Credit: OLJ archive)

Mansour Labaky, in the Madeleine church, next to Bernard Porte, in 1987. (Credit: OLJ archive)

The complaint lodged by Labaky’s defense team with the Baabda Criminal Court, which L'Orient-Le Jour reviewed, alleges that a “group of resentful and liars” set up an “alliance of villains” called “the Saint-Antoine alliance,” seeking “vengeance, slander, defamation, insult and fabrication of lies.”

L'Orient-Le Jour tried to contact Florence Rault, Mansour Labaky’s French lawyer, but did not receive a response.

“There is no doubt regarding the ruling (of Caen). It is not a problem for the victims if he will be sentenced to five, 10 or 20 years in prison, as long as he is officially convicted for the crimes he committed,” Doumic said before the court’s ruling.

The Lebanese defense relied on a series of 2,000 emails that the Church authorities and alleged victims had exchanged, found in a box deposited on Mansour Labaky's doorstep in 2013 by “the Divine Providence.”

The victims’ names circulated on social media.

“It is not only illegal to take possession of a correspondence, and to make it public, it is even worses to use it so as to alter its meaning,” Doumic, who was summoned by a Lebanese criminal court in a defamation case filed following an interview she had with the LBC TV channel in May 2016, said.

In the complaint that Labaky’s defense filed before the print media court in Beirut, the French lawyer is accused of carrying out a media campaign based on “slander” and “public defamation,” among other charges.

“Secretly dismissing a priest”

In an automatic response to this judicial outpouring, the Maronite Church decided to defend itself by sending out its missionaries on a crusade against all those who dared to tarnish Labaky’s integrity.

“According to it, an attack against one of its members is an attack against the Church as a whole. However, it is time that the Eastern Churches improve transparency when dealing with the abuse of minors, instead of secretly dismissing a priest,” the aforementioned Lebanese priest who declined to be named says.

The hacked emails landed on Pope Francis’ desk, sent by Patriarch Bechara al-Rai himself. On March 18, 2016, the cardinal appeared in a video during a visit to the Collège Saint Joseph in Antoura, where he publicly defended Labaky, denouncing a “well-orchestrated slander campaign” against him. He indicated that he had sent the Vatican “the records that prove these lies.” Under Rome’s pressure, he retracted a few days later.

On May 8, 2016, Lebanese media outlets reported that the patriarch had travelled to Lisieux to inaugurate a chapel dedicated to Lebanon. Nearly 3,000 people attended the inauguration ceremony. However, behind closed doors, another development had taken place earlier.

“The bishop of the diocese of Bayeux-Lisieux, Mgr. Boulanger, warned Cardinal Rai in advance that he would not enter his diocese if he did not meet with Mansour Labaky’s victims,” Ghanem said. She was the only Lebanese there who presented herself as a victim of Labaky, along with several French victims.

These remarks were confirmed by Father Laurent Berthout, the spokesperson for the current bishop.

“This meeting was held before Mass. The victims gave their testimonies and Cardinal Rai was shaken and very disturbed by what he heard,” the French priest said.

Labaky’s supporters even used a dedication from the pope as a desperate last-minute attempt at proof of his “innocence.” In 2019, the Ambassador of Lebanon to the Holy See, Antonio al-Andari, had the Sovereign Pontiff dedicate his book “God is Young” to the latter, and sign, “To Father Mansour Labaky, with my blessing, François.”

Five years later, Labaky’s defenders have run out of steam. Victims have begun to open up more about their stories of abuse, particularly since Pope Francis, who proved to be intolerant, said he was saddened by the publication of the Sauvé report on sex abuse against children in the French Catholic Church last month.

After keeping a vague stance for years as to whether Mansour Labaky is guilty or not, the Maronite Church is clear now.

“We adopt the Vatican’s position, which is why we passed a law in November 2016 against sexual abuse of minors. As far as I know, Father Labaky is still secluded in the convent,” affirms the Patriarchal Maronite Vicar Hanna Alwan. The Maronite Church is said to be currently examining cases of priests suspected of pedophilia, according to Alwan.

In 2010, even before the investigation started, Mansour Labaky took up his pen to defend through L’Orient-Le Jour’s columns the Church which had been under attack, according to him, from all sides.

“Pedophilia is a disease, similar to cancer, which needs to be cured,” he wrote, in what seemed as a manifesto. He added, “In each one of us lies a great sinner capable of every turpitude and a great saint capable of being according to God’s heart.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury and Sahar Ghoussoub.