President Michel Aoun (center) discusses the maritime border issue with government officials in a meeting at Baabda Palace. (Credit: Dalati & Nohra)

As long as Lebanon has not officially announced a revision of its maritime sovereignty and has not lodged a formal claim with the United Nations for an extra 1,430 square kilometers of territory, the loud objections made by the Lebanese authorities as Israel moves forward in the offshore oil and gas exploration dossier will remain meaningless. Technical and legal experts’ opinion on the matter is categorical. The issue of demarcating Lebanon’s southern maritime border — over which talks have been frozen since May 2021 following Lebanese one-upmanship — is subject to unforeseen developments.

Israel engaged last week in new administrative procedures in preparation to explore for hydrocarbon in the northern part of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The American firm Halliburton announced that it has been awarded a contract to drill three to five wells there on behalf of Energean, an international energy company.

While Halliburton did not specify which zone these wells will be drilled in, it indicated that the contract “follows a successful four-well offshore drilling campaign that it previously executed in the Karish and Karish North gas fields.”

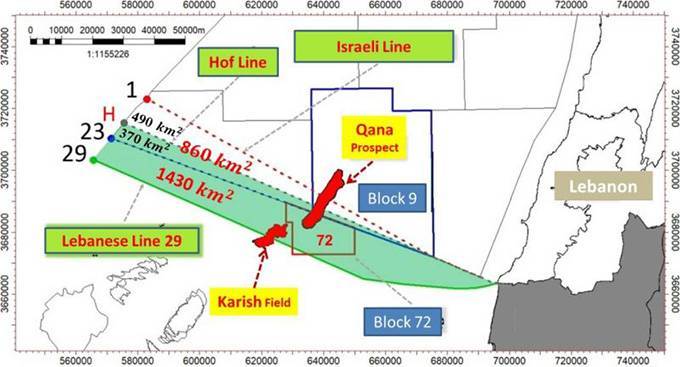

This area is located south of Line 23, which delineates an 860-square-kilometer triangle that Lebanon claimed the right to before the UN in 2011. It is also part of the 1,430-square-kilometer area delineated by Line 29, which the negotiating team and the Lebanese Army claimed in December 2020 is within Lebanon’s EEZ, based on a 2011 report by the United Kingdom’s Hydrographic Office.

A map showing Line 23, the southern extent of Lebanon’s official claim, and Line 29, which has been claimed at the negotiating table but not through any legal process. (Credit: Lebanese Army)

A map showing Line 23, the southern extent of Lebanon’s official claim, and Line 29, which has been claimed at the negotiating table but not through any legal process. (Credit: Lebanese Army)

The letter to the UN

These developments triggered immediate outrage in Lebanon. The Lebanese political caste, chiefly the Parliament speaker, denounced over the weekend what they described as Israel’s violation of the maritime border framework agreement under which the neighboring foes agreed to talk.

Speaker Nabih Berri said the tender for exploration and contracts awarded by Israel “in a disputed maritime area” violate the framework agreement and “threaten international peace and security.”

Prime Minister Najib Mikati instructed Foreign Minister Abdallah Bou Habib to ask the relevant international bodies to “prevent” Israel from drilling in the disputed area.

In a letter addressed to Secretary-General António Guterres, Amal Mudallali, Lebanon’s ambassador to the UN, called on the body to “prevent any future drilling in the disputed area,” and to ensure that the drilling works announced in the Karish field “are not located in the disputed area.”

On Sept. 21, President Michel Aoun met with Mikati and Bou Habib at the Presidential Palace. The following day, Aoun said he wanted to “resume indirect negotiations” to demarcate the border.

However, is the area where Israel plans to drill disputed, as Lebanese officials claim? If yes, on which legal basis is that claim founded? And if not, what are the reasons behind this political grandstanding?

Amending Decree 6433

According to Laury Haytayan, an oil and gas governance expert who closely follows maritime border demarcation negotiations between Lebanon and Israel, the Jewish state’s move “focused on the Karish North hydrocarbon field and Block 12,” located between the Karish and Tanin blocks, and “is indeed located in Israeli territorial waters.”And for good reason: “President Aoun did not sign the amendments to Decree 6433 of 2011, which aims to rectify the [maritime border] map that Lebanon submitted to the UN” that year. The map delineates an 860-square-kilometer triangle, bounded by lines 1 and 23, that both countries claim.

Then-caretaker ministers Michel Najjar and Zeina Akar had signed the amendments on April 13, which were awaiting only the head of state’s signature. Today, because a new cabinet has been formed, the amendments require the government’s approval.

“The only reply that the Lebanese authorities can expect from the UN today is that the Israeli actions are located outside the disputed area based on the maps Lebanon submitted,” Haytayan says.

“While it has been more than 159 days that nothing has happened on the Lebanese side, the Israeli matter takes its natural course,” she says. Unless the new cabinet approves the amendments to Decree 6433, Lebanon’s appeal to the UN will remain weightless.

Marc Ayoub, an energy researcher at the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute, agrees that “we cannot speak of a disputed area” when discussing Israel’s drilling preparations, because “Lebanon has never officially, politically or legally claimed the right to Line 29 as its maritime boundary line, which is backed by the UKHO.”

Therefore, “the Lebanese letters of protest to the UN will necessarily be followed by UN verifications, which will conclude that the drilling plans are located outside Line 23. … In this vein, the loud objections made by the political class are only a kind of one-upmanship,” he says.

Obstruction benefits Israel

What can the Lebanese authorities do instead? “Only by approving the amendment to Decree 6433 in the cabinet and by submitting it to the UN can Lebanon assert its rights,” Ayoub says. “This approach will make it possible to specify as disputed the area where the Israeli actions are planned.”

Another legal expert, who declined to be named, also said this approach was the only possibility for Lebanon to stop Israel from moving forward on the oil and gas file.

“Adopting the amendment and submitting it to the UN is the only way to stop Israel and get it back to the negotiating table,” he says.

The maritime border negotiations between the two countries, still bound by the 1949 armistice agreement, have been paused since May 2021. “This situation suits [Israel] perfectly, because it leaves them a free hand,” the expert says.

The ball is now in the court of the new, Mikati-led government, which may decide to adjust tactics, particularly because the Lebanese position, as expressed by Decree 6433, is subject to change if new information is added — unless decided otherwise for political considerations.

This article was originally published in French in L’Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.