A patient experiencing symptoms of so-called long COVID undergoes treatment at the American University of Beirut Medical Center. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — When 45-year-old Caline Mouawad contracted COVID-19 in January, she hardly noticed — everything felt more or less normal, apart from a slight fever. Four months later, she is so exhausted, she can hardly get through the day.

“I simply cannot pull myself out of bed,” she told L’Orient Today. “I get up at 12 p.m. to make lunch for my kids and then go back to sleep.

“I have had to stop everything,” including her work as a lawyer, she said.

After visiting multiple doctors over the past few months without getting answers, a psychiatrist finally diagnosed her three weeks ago with “long COVID” — an umbrella term for a host of symptoms experienced beyond 12 weeks after an initial COVID-19 infection.

“When I heard this term I felt good, because now that I have a name for what I’m feeling, I have something to fight,” Mouawad said.

Although new daily cases of COVID-19 have fallen significantly in Lebanon since the surge of infections at the beginning of this year, the virus continues to pose a significant threat, especially as most restrictions have now either been relaxed or lifted entirely. Meanwhile, the national vaccination rollout is still progressing slowly, with less than 5 percent of the adult population having received two doses.

Tens of thousands of residents in Lebanon may be experiencing long COVID, whose symptoms range from fatigue, loss of smell or taste and breathlessness, to insomnia, anxiety, memory loss and difficulty concentrating. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Tens of thousands of residents in Lebanon may be experiencing long COVID, whose symptoms range from fatigue, loss of smell or taste and breathlessness, to insomnia, anxiety, memory loss and difficulty concentrating. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

The health system is now presented with a new obstacle — treating the disease’s long-term effects.

“Since the start of the pandemic, we as physicians have faced a lot of challenges,” says Ola Mazboudi, a pulmonary specialist and the head of the COVID-19 unit at Hammoud Hospital University Medical Center in Saida. “First, treating a virus we knew nothing about. Second, the vaccine. And now what I call the hidden monster — post-COVID syndrome.”

Global studies suggest that 10–30 percent of people who contract COVID-19 suffer symptoms for months afterward, and in some cases for a year or more. These people are often referred to as “COVID long-haulers,” while the condition itself is called “long COVID” or “post-COVID syndrome.”

A survey of more than 1,000 people conducted by the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom found that seven in 10 people who were admitted to hospital for coronavirus had not fully recovered after five months, and that one in five had symptoms so severe that they could be classified as a disability.

Although research into the long-term effects of COVID is in its early stages due to the recent nature of the pandemic, studies have also found that post-COVID syndrome is having a serious negative impact on long-haulers’ lifestyle.

Research conducted at the University of Washington School of Medicine found that 30 percent of COVID long-haulers reported a worse quality of life compared with before they contracted the virus, and 8 percent were no longer able to complete daily chores.

The University of Leicester researchers found that of those who were working before contracting COVID-19, 17.8 percent were still not able to work 5 months later, and nearly 20 percent experienced a “health-related change” to their work.

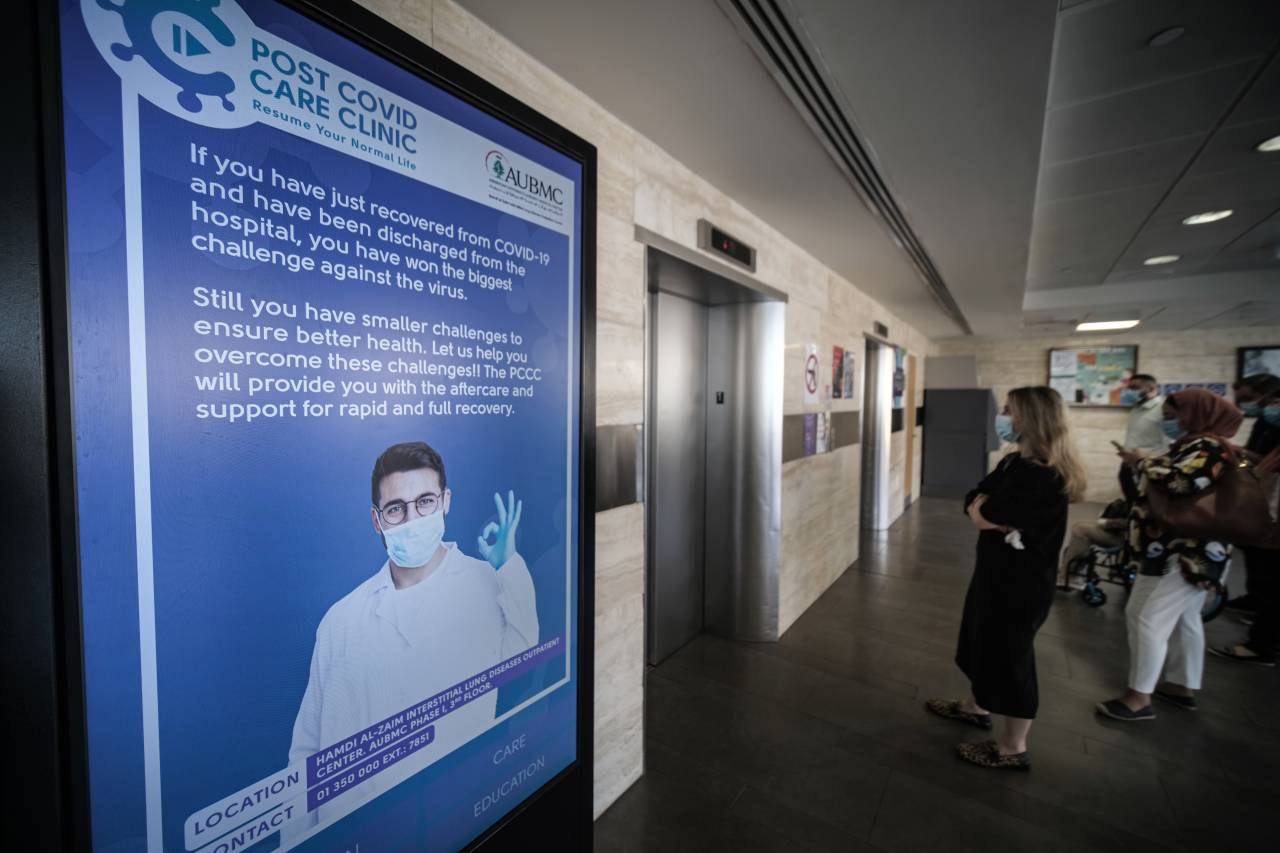

AUBMC’s specialized post-COVID care clinic, the first of its kind in Lebanon, deploys a range of treatments to help patients experiencing a wide array of symptoms on the road to recovery. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

AUBMC’s specialized post-COVID care clinic, the first of its kind in Lebanon, deploys a range of treatments to help patients experiencing a wide array of symptoms on the road to recovery. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

No data is available on how many people in Lebanon have experienced or are currently suffering the symptoms of long COVID. It is difficult to even make estimates, as the total coronavirus case count reported by the Health Ministry — 535,754 as of Sunday — shows the total number of positive tests, not the number of individuals who have contracted COVID-19.

Epidemiologists have also suggested that the actual number of COVID-19 cases could be far higher than what has been reported, mainly due to low testing.

“We don’t have numbers on long COVID in Lebanon, so we don’t know exactly how many people are being affected,” says Mohammad Haidar, a physician and medical adviser to caretaker Health Minister Hamad Hassan.

However, using very broad estimates based on global studies on long-COVID prevalence, tens of thousands of people in Lebanon could potentially be dealing with long-term symptoms of the disease. A Facebook group called COVID Survivors in Lebanon, where people discuss their shared symptoms and post requests for blood donors who have recovered from COVID-19, has almost 4,000 members.

Varied symptoms, complex treatment

The symptoms experienced by COVID long-haulers vary widely, from fatigue, loss of smell or taste and breathlessness, to insomnia, anxiety, memory loss and difficulty concentrating, known as “brain fog.”

“The thing about this syndrome is that it appears to affect those who had mild to moderate COVID and young patients or even children,” Mazboudi says. “We have many young patients who were healthy before getting COVID-19 but afterward weren’t able to return to their regular lifestyle.”

Mirvat Termos, a 24-year-old public health doctoral student, contracted COVID-19 in March 2020. She says that for about a year afterward, she was struggling to concentrate for long periods of time and was constantly exhausted, unable to sit down and work.

“I’m healthy. I’m young. I have no comorbidities. But my COVID-19 infection was debilitating,” she says.

Much of the rhetoric surrounding COVID-19 infections, both in Lebanon and globally, has focused on the need to protect older people and those with chronic diseases, who are most at risk of severe illness and death.

However, many young, healthy people who led active lifestyles before contracting the disease are now suffering from long-term complications after experiencing relatively mild COVID-19.

“It’s not just about you dying from COVID, as this is a very small proportion of individuals, but so many have debilitating symptoms for months afterward,” says Termos, who is also a member of the Independent Lebanese Committee for the Elimination of COVID-19 (ZeroCovidLb).

Like Mouawad, Termos visited several doctors and underwent dozens of tests to try to find a diagnosis for her condition, but to no avail.

“They didn’t understand why I was going through what I was — there was no biochemical explanation,” she says.

Researchers are still unsure what causes the long-term effects of a COVID-19 infection, though various studies have drawn links to severe organ damage, inflammation, post-traumatic stress disorder and reduced immune response.

Because post-COVID syndrome is still not well understood and the symptoms vary so widely, prescribing appropriate treatment is a challenge.

“There is no specific treatment protocol for post-COVID syndrome,” says Pierre Bou Khalil, a pulmonary and critical care doctor at the American University of Beirut Medical Center. “We look at what doctors around the world are doing in terms of treatment and medication, and sometimes we may do the same.”

Bou Khalil is part of a small team running AUBMC’s specialized post-COVID care clinic — the first of its kind in Lebanon. The center provides a range of services to assess patients’ persisting symptoms and refer them to a relevant specialist in hopes of finding appropriate treatment.

“We have a comprehensive program. It doesn’t only rely on lung doctors, but on a group of doctors to take care of the patient, including psychiatrists, rheumatologists, and ear, nose and throat specialists,” Bou Khalil says.

Demand is high. The clinic is currently operating at its capacity of 180 patients a month.

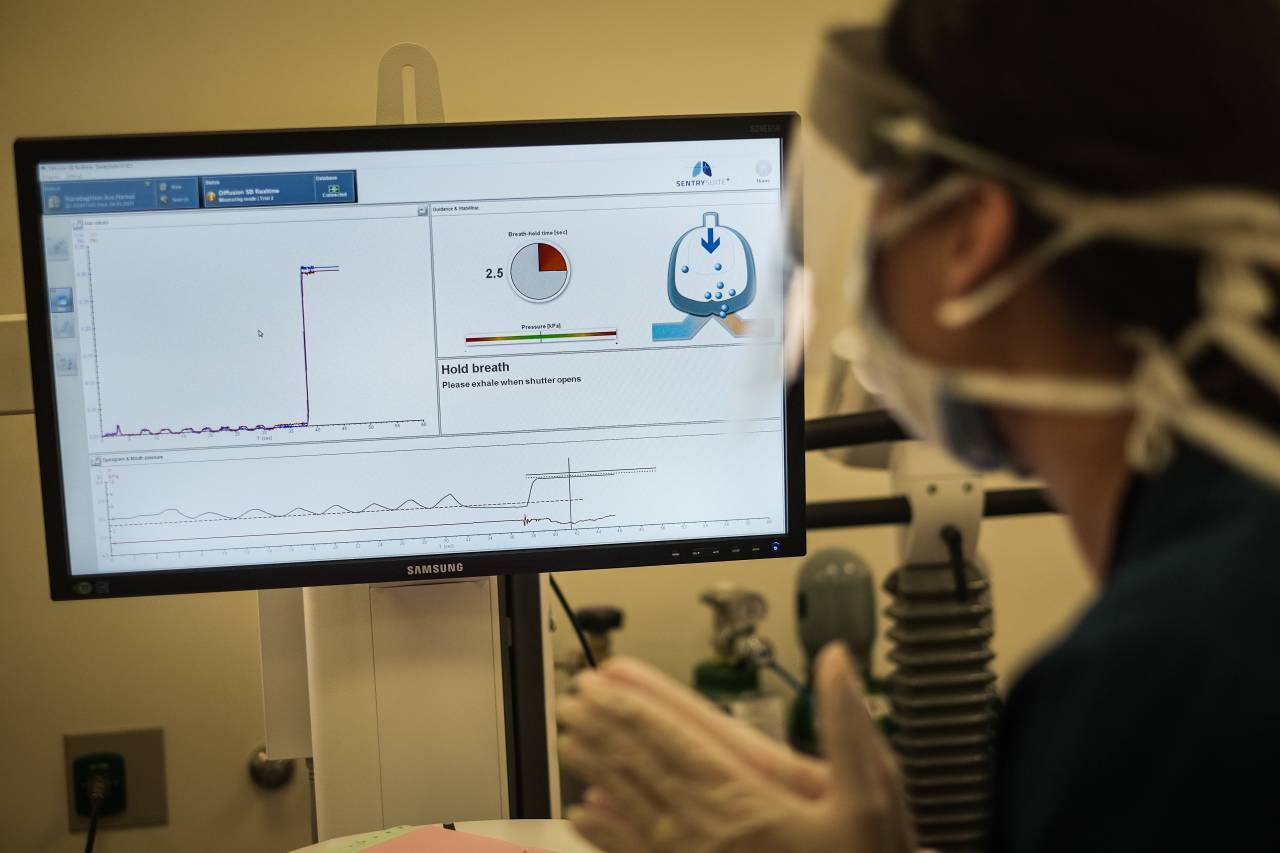

Inside the clinic’s pulmonary testing unit — a room that looks more like a high-tech facility for measuring the endurance of elite athletes — 52-year-old Ara Karadaghlian has his mouth clamped over a plastic tube, breathing in and out at the command of a pulmonary lab technician.

In January, as Lebanon was approaching the peak of COVID-19 infections, Karadaghlian caught the coronavirus, but like the others L’Orient Today spoke with, had only mild symptoms such as a slight headache and a cough.

He is now being treated at AUBMC’s specialist post-COVID clinic to help him recover from ongoing struggles with breathing and stamina.

“I am getting tired really quickly, even just walking down the street,” he says.

He is put through his paces for about 10 minutes in a series of tests that leave him visibly worn out. Meanwhile, another patient steps into the corridor for a “six-minute walking test” to assess her aerobic capacity and endurance.

Down in Saida, Hammoud Hospital does not have a dedicated post-COVID clinic, but doctors regularly treat patients suffering from ongoing effects of the disease. Like at AUBMC, the hospital takes a “multidisciplinary approach” to cover the range of symptoms, Mazboudi says.

“We have pulmonologists, psychologists, cardiologists on board,” she explains. “When a patient comes to me, I am able to refer them to the relevant specialist for treatment.”

Despite medical professionals’ efforts, many who experience symptoms of long-COVID have difficulties dealing with them due to a general lack of information about and recognition of the syndrome, both among the general public and in the medical community.

“There is very little awareness of this condition, even among doctors,” says Mazboudi, who lectures on post-COVID syndrome to fellow health professionals and members of the public. “Some are dismissive and say patients are just complaining. But [patients] are not making it up.”

Caline Karam, a 24-year-old student, told L’Orient Today that several doctors dismissed her when she tried to seek help for breathlessness, fatigue and hair loss that she has experienced since contracting COVID-19 in January.

“I have had issues with my weight, and doctors tend to tell me that [my symptoms] are because of my weight,” she said. “But I know that a month before I got COVID-19, I would do the same task and wouldn’t feel as exhausted as I do now.”

“If I’m out walking it feels suffocating and I need to stop and breathe, which is something that never happened before,” Karam continued. “All I am doing now is trying to take things easy. It hasn’t got any better, but I’ve gotten used to it.”

Termos, the public health doctoral student, says she uses Twitter to connect with fellow health researchers, and that “whenever I tweeted about it, people accused me of fear mongering or I was met with disbelief.”

“It was only when a member of my family contracted COVID in December and then became a long-hauler that he understood what I was talking about,” she adds.

Long road to recovery

With Lebanon’s health sector already strapped for cash, personnel and other resources amid the ongoing pandemic and the economic crisis, the state seems unlikely to be able to deliver these new patients the comprehensive services needed to help them on the road to recovery.

“In Lebanon we not only don’t have enough resources available for long haulers, but those long haulers themselves might not be able to access the resources that are there” due to the economic crisis and civil unrest, Termos says.

While in principle the Health Ministry provides health coverage for uninsured residents — almost 50 percent of the population, according to 2018 figures from the Central Administration of Statistics — the public health sector is currently under immense strain due to rising costs of medicine and equipment, huge debts owed by the state, the emigration of health professionals and increased workload.

With Lebanon’s health sector already cash strapped and facing supply shortages, long COVID patients may face an uphill battle securing affordable care. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

With Lebanon’s health sector already cash strapped and facing supply shortages, long COVID patients may face an uphill battle securing affordable care. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Firass Abiad, the head of the country’s largest public health facility, Rafik Hariri University Hospital, has on multiple occasions pointed to congestion in the hospital’s emergency room as evidence that more and more patients are turning away from the private health care system because of financial constraints.

“Post-COVID syndrome is something to worry about … especially with the economic situation,” Mazboudi says.

Haidar, the ministry adviser, appears less concerned with the burden post-COVID syndrome could place on the health system, saying that because its symptoms can be addressed by existing specialists, the public health sector already has the tools available to treat patients and requires no special directives from the ministry.

“All patients with the syndrome will be able to benefit from health coverage from the ministry, of course,” he said, adding that treatment “shouldn’t be an economic issue.”

Meanwhile, it is still not known how long post-COVID syndrome lasts and whether someone can ever fully recover.

A small survey in the United States found that long COVID patients may start to feel better after receiving an RNA messenger vaccine such as those produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna.

Termos says she only began to return to feeling normal when she received her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in March this year — 12 months after her initial infection.

With vaccination rollout still low and research on long COVID limited, treating so-called long-haulers “is an ongoing battle,” Mazboudi says, “but we are seeing a difference when people come to us for help.”

At AUBMC, the majority of patients coming to the post COVID-19 clinic are also getting better via thorough treatment and rehabilitation, Bou Khalil added.

However, “the difference month to month is minimal,” he continued. “It is a snail-paced recovery.”

Those without access to state-of-the-art treatment face perhaps a steeper uphill battle.

“I am trying to force myself every day to get out of bed a little earlier and do some gentle exercise,” Mouawad said. “But still, I feel exhausted.”