Mounira Al Solh. (Credit: Barry Pells. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

BEIRUT — Mounira Al Solh is not new to sewing.

“When I was a kid, my mom came up with a soothing activity to help me relax before trying to sleep,” the artist recalls. “I was allowed to cut a hole in my pajamas, then stitch it up again. That was really something. Parents didn’t let their children do such things.

“Kids in our building used to come to draw on our bedroom windows. My mom allowed this. Perhaps she initiated it.”

The nurturing aspects of Solh’s upbringing played out in counterpoint to a more grim rhythm.

“Growing up during the bombs and the fighting [of Lebanon’s Civil War] made sleep very scary ... Many people of my generation still have sleeping problems, I think ... During heavy bombardments, I often slept between my parents, hoping that at least we’d all end together. My biggest fear was becoming an orphan, of what might happen if you’re left alone.”

Since her youthful introduction to needlework, the artist has come to embrace multiple forms and media — painting and drawing, video installation, sculpture, writing and performance, as well as embroidery. Frequently playful, often ironic and self-reflective, Solh’s work can seem either politically engaged or escapist. She’s interested in intimate histories, women’s stories especially, and has engaged with themes of conflict, resistance, displacement, loss and memory. Complementing these themes, her practice embraces the skills and stories of collaborators.

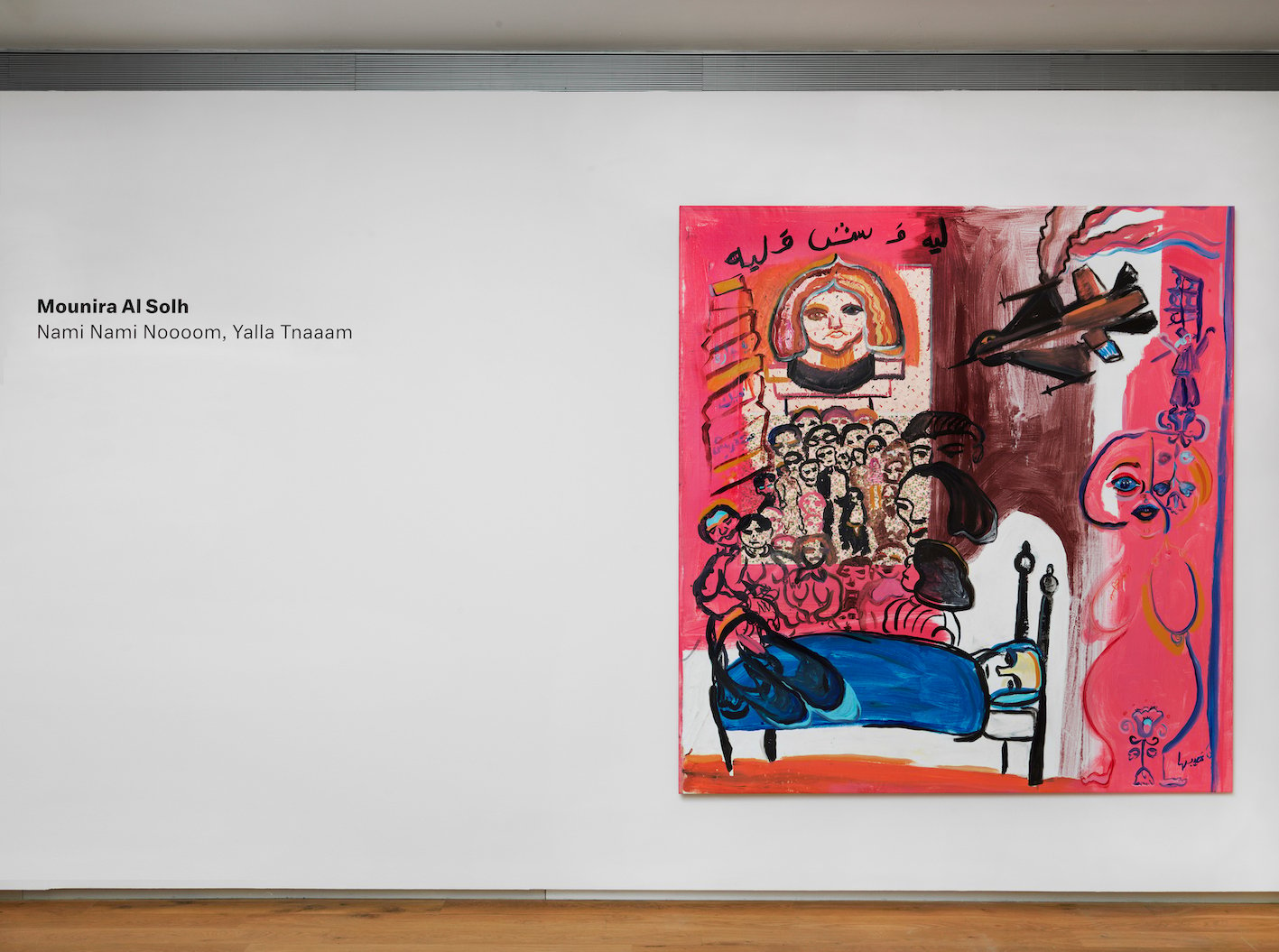

“Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023. Exhibition view, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023. Exhibition view, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“Nasibak, your destiny,” 2023. Exhibition view, “Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“Nasibak, your destiny,” 2023. Exhibition view, “Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

This is the sort of work that visitors can expect to find at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (April 20- Nov. 24), where the Lebanese pavilion will host a solo show of Solh’s new work.

Honoring the customary pre-biennial press embargo, Solh won’t discuss what she will show at Venice. That said, the run-up to the event has been eventful for her — having won the Netherlands’ prestigious ABN AMRO Art Award and been shortlisted for the UK’s Artes Mundi Prize. From a location outside Amsterdam, where she spends time when not in Beirut, Solh talked about the constant concerns underlying her restless practice and some of the recent work that has emerged from it.

Unpacking the tent

Solh is a great maker of tents. This series is rooted in her encounters with displaced Syrians, many of them young activists who turned up in Mar Mikhael (the Beirut district where she had her studio) after 2011, having fled the Syrian state’s violent crackdown on civilian demonstrators inspired by the Arab Spring.

“I met many people of different backgrounds, some from minority groups, courageous people standing up to four decades of dictatorship,” she recalls. “I was scratching down our conversations and sketching their portraits on pads of yellow paper. It was very tough. Many of them had lost someone in Syria.”

“A night hour as long as night,” 2022. Exhibition view, Artes Mundi 10, 2023, The Cardiff National Museum, UK. (Credit: Polly Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“A night hour as long as night,” 2022. Exhibition view, Artes Mundi 10, 2023, The Cardiff National Museum, UK. (Credit: Polly Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“A day is as long as a year,” 2022. Exhibition view, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK. (Credit: Rob Harris © 2022 BALTIC. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“A day is as long as a year,” 2022. Exhibition view, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK. (Credit: Rob Harris © 2022 BALTIC. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

The mixed-media drawings and texts that came out of these encounters (originally on Lebanese-produced legal paper) are the basis of Solh’s ongoing series, titled “I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous.” She borrowed the title from a line by Mahmoud Darwish, reflecting upon how he would have preferred to write poetry about something other than the dispossession of Palestinians.

Solh’s engagement with the stories of displaced people found a more formally elaborate expression while preparing for the contemporary art event Documenta 14, co-hosted in 2017 by Kassel and Athens. There, at the city’s Benaki Museum, she discovered the sperveri, or bed-tent — a bridal bed equipped with a canopy for privacy, common in 17th- and 18th-century Rhodes.

“Women in Rhodes would spend a couple of years stitching their sperveri’s embroidery before wedding,” Solh says. “Symbolically it’s where the couple would first meet for conceiving children, [but also] trauma. People who have to marry this way often have rather unpleasant first nights, I think.”

While researching the history of Mediterranean embroidery, Solh found common motifs dispersed across a wide geographic area, indifferent to borders, language and religion.

“In Greece, they have embroidery of cypress trees, which is also common in Palestinian embroidery. It sometimes symbolizes grief and in some Mediterranean countries, people are buried beneath cypress trees. Women working on sperveri often embroidered two peacocks drinking from a water fountain, a symbol of fertility. This design can be traced to Byzantine times, even further back to Mesopotamia.”

“I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous,” 2012-ongoing. Exhibition view, The Mother of David and Goliath, 2019, Sfeir-Semler, Karantina, Beirut, Lebanon. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous,” 2012-ongoing. Exhibition view, The Mother of David and Goliath, 2019, Sfeir-Semler, Karantina, Beirut, Lebanon. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Embroidery motifs accompanied people as they moved from one region to another, Solh remarks, not unlike the dissemination of proverbs — the stuff of her 2010 video work “The Mute Tongue,” in which a Croatian performer enacts a series of 19 Arabic proverbs.

Solh’s “Sperveri,” 2017, recreated a four-meter-high bridal tent, reproducing some of its original decorative elements while introducing new motifs and, most importantly, stories of those displaced women she’d encountered in the previous half-dozen years.

“I hung the stories in the tent, matching a historical embroidery motif to each story, so you may recognize a connection between the two. I consider ‘Sperveri’ a breathing library of stories that must be remembered ... Instead of a bed for nuptial trauma, the tent holds a memorial for lost loved ones.”

To stitch the tent’s embroidered patterns and story texts, Solh worked with a group of veteran embroiderers in Lebanon and the Netherlands, women usually a decade or two her senior who taught her a lot about the craft.

“It took 90 minutes to embroider a single line” of text, Solh recalled. “They were so perfectly stitched, people sometimes didn’t notice they were sewn.”

Solh’s tent series has proliferated. Some pieces, like a triptych of works celebrating women in Lebanon who defy patriarchy, strongly echo “Sperveri.” Others find inspiration in the long tradition of sumptuously decorated tents historically commissioned by men who ruled the MENA region, heading states founded on nomadic culture — Arab, Turkish or Iranian. Solh’s 2022 work “A day is as long as a year,” for instance, is a replica of an Iranian imperial tent from the reign of Mohammad Shah (1834-1848).

“At that time, the more tents a ruler had, the more powerful he seemed. My version is devoted to saving the stories of those who have the least power in our societies,” she says. “When you enter, you can read the stories of seven women of various backgrounds. Each is written both in the woman’s mother tongue — usually Arabic or Farsi — as well as English. All are stories of women refusing to be victims.”

“Sperveri,” 2017. Exhibition view, Documenta 14, 2017, Museum of Islamic Art, Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece. (Credit: Yiannis Hadjiaslanis. Courtesy of the artist, Sfeir-Semler Gallery and Documenta 14)

“Sperveri,” 2017. Exhibition view, Documenta 14, 2017, Museum of Islamic Art, Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece. (Credit: Yiannis Hadjiaslanis. Courtesy of the artist, Sfeir-Semler Gallery and Documenta 14)

Solh’s contribution to the Artes Mundi Biennial, on show at the National Museum Cardiff, includes “A night hour as long as night,” 2023, an installation that the artist describes as ‘a sister’ of “A day is as long as a year.”

“This tent’s raison d’être is the story of an outstanding Lebanese woman I know,” Solh says, “who, during the Civil War, defied religious and social stigmas and married a much younger man from a different background.”

There are strong formal similarities between the two pieces, but the more recent work has stripped the tent’s decorative elements from any formality of function. At the center of the installation is a stylized miniature tent, resembling a flying saucer, of embroidered green fabric. Suspended in a semi-circle behind it is an array of seven panels, embroidered and painted in blue and green. While the embroideries of the Mohammad Shah replica evoke Arabic terms for “happiness” and “sadness,” this sister work stitches samples from a list of 100 synonyms for “love” — longing, nostalgia, relationships, madness, etc — compiled by Damascus-born Hanbali jurist and theologian Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292-1350).

“The curators and organizers in Cardiff connected me with two amazing women who created the Oasis One World Choir. It’s made up of a diverse group of outstanding voices — migrants, asylum seekers and local people. I was lucky that they agreed to work with me. We prepared a live performance for the opening that we presented in late October 2023. I think [the performance and the timing of the show] brought new meaning to the exhibition.”

The historical antecedents of Solh’s tents may vary, but in all cases, she is reshaping moveable shelters into spaces that exhibit the stories of strong individuals made powerless by circumstance. Tents have long been part of the visual iconography of displaced people in this part of the world — whether the shelters provided by UN agencies or improvised from billboard images for luxury brands. It’s notable that Solh’s work abjures such documentary models in favor of beautiful objects of historic design, ennobling contemporary migrations that are all too often depicted in terms of criminality.

A still from “The mute tongue,” 2010. 19-channel video installation. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

A still from “The mute tongue,” 2010. 19-channel video installation. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Foreigners everywhere

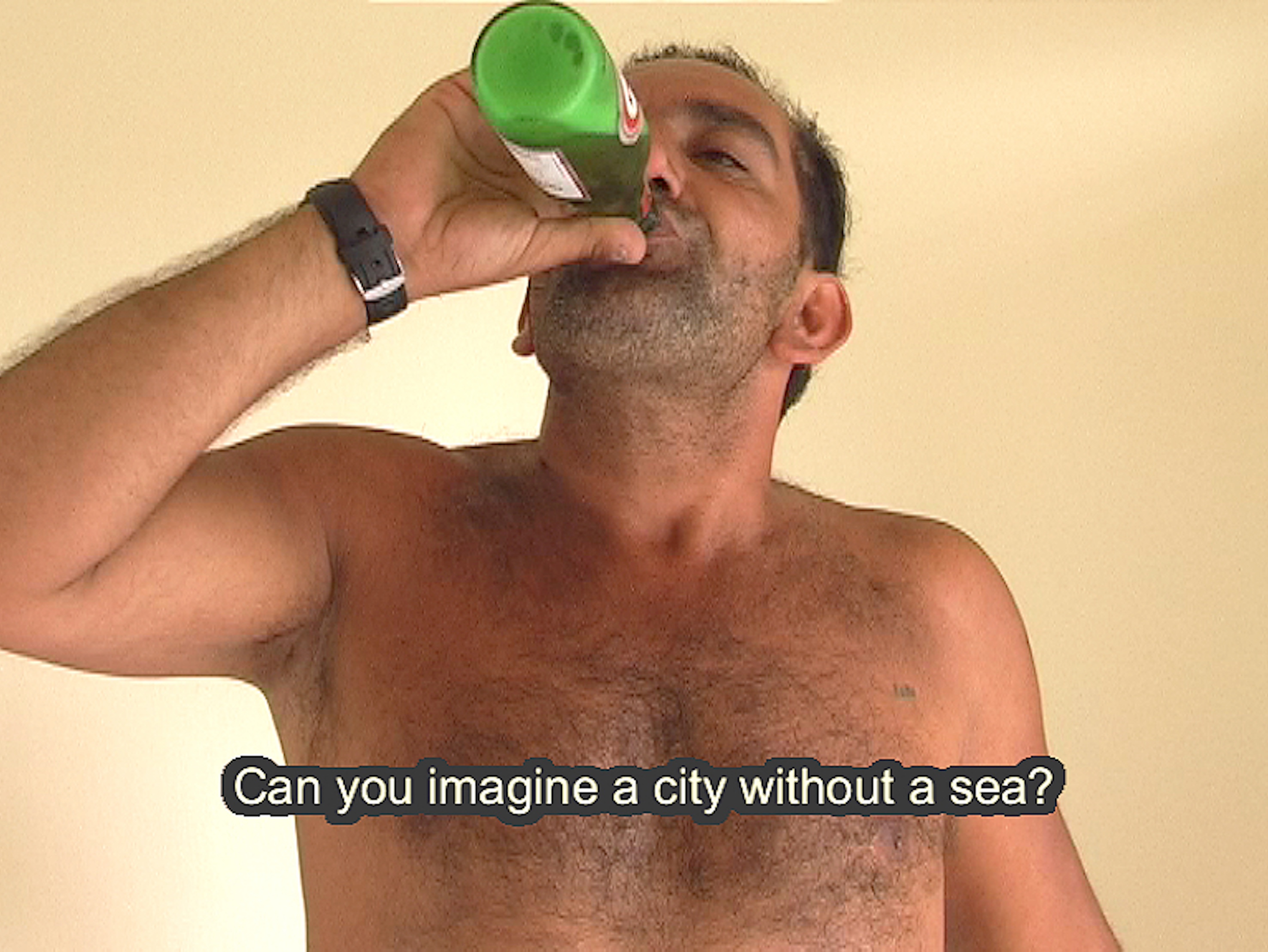

Displacement is among the central themes of Solh’s work, but much of her oeuvre predates Syria’s ongoing tragedy and Europe’s migrant crisis. It resonates through some pieces she made while studying in Amsterdam — amusing works in video whose subject matter lands close to home.

Take “The Sea is a Stereo,” 2007-10 — a mockumentary about the artist’s father and his circle of male friends who regularly bathe in the crystalline waters off the rocks of northwestern Beirut — in which Solh’s voiceover ventriloquizes the male swimmers’ testimonials. Playful tone notwithstanding, the artist sees continuities linking this piece with her tent series.

“At the time the status on my Dutch residency permit was ‘student,’” she recalls. “I was thinking about the social marginality of students. If you come from abroad, you’re not local and not a migrant. You may have a job but you're not really a worker. I thought, once my father and his friends go to the beach to be together, their position in Beirut is also a bit marginal. They're not typical citizens anymore. It’s almost as if they emigrate, but they're not going to land anywhere else, just in the sea.” She laughs. “The time they spend by the sea, it’s a bit like being in a nowhere.”

‘Let’s Sleep’ in Amsterdam

After winning the ABN AMRO Art Award, Solh’s exhibition “Nami Nami Noooom, Yalla Tnaaam” (Sleep, sleep, sleep, let’s sleep) opened at H’Art Museum (formerly the Hermitage Museum in Amsterdam) in November 2023. As the show’s title suggests, the work at H’Art springs from the wartime sleeping game Solh’s mother devised when she was a youngster.

“Some years back I remembered the pajamas story,” she says, and began to develop a series based on cutting holes in various textiles. Instead of closing them, “I stitched around the hole to mark it, embroidering the opening to let the memories and thoughts pass through it.”

Working in her Mar Mikhael studio in 2020 Solh, then a new mother, was preoccupied by the prospect of soon having to relocate to the Netherlands, to formalize her residency status. By chance, she was not in the studio when the port exploded on Aug. 4, 2020, but the blast tore a gouge from her and her practice.

A still from ‘The sea is a stereo: Paris Without a Sea,’ 2007-08, video,13:07. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

A still from ‘The sea is a stereo: Paris Without a Sea,’ 2007-08, video,13:07. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“Friends, neighbors, were gravely hurt. Like many others on that day, I felt that in a few seconds, war had returned to Beirut … It was really dark, this period. I felt terrible and guilty to be leaving. There was like a black hole and it took me some six months to kind of—”

She exhales. “Then I could really visualize it. Maybe that was when I connected my Civil War memories to what we were going through in 2020 ... A year and a half later it made me start cutting and stitching my pajamas again, and there was other work — paintings, collaborative projects.”

The H’Art show exhibits a series of paintings on the theme of dreams and nightmares, hung in counterpoint to an installation of stitched pajamas that grew out of a collaborative project Solh ran in 2022-23.

“I worked with a number of women in this project,” she recalls. “Some Lebanese and some Dutch citizens — locals and several with migrant backgrounds. I collected many used pajamas, a lot of them worn out. Amazing cotton robes came to me, some made in Lebanon, others from second-hand shops — their floral elements remind me of pajamas from Damascus.”

Solh’s collaborators brought their favorite old nightclothes to the project. “One woman, who had emigrated to the Netherlands, brought me pajamas that she only wore in summertime when she visited her family in Turkey. They’d lasted her 30 years! It was really touching to hear stories like these.”

All told she compiled some 100 pajamas this way, 50 of which are on show at H’Art.

“The show’s opening was very interesting,” Solh smiles. “Usually people don’t touch artworks, but as each contributor was showing her own pajamas, telling her stories, everybody was touching them. I think this may be one of the most sustainable art projects I’ve worked on. These things, destined to be thrown away maybe, now got a new life — on display in an Amsterdam museum.”

Solh’s paintings and pajamas are accompanied by a sound piece based on recordings of some of her collaborators’ children, singing lullabies in their various mother tongues, including Arabic and Dutch.

“Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023. Exhibition view, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“Nami nami noooom, yalla tnaaam,” 2023. Exhibition view, H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (Credit: Gert Jan van Rooij. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“It mirrors the plurality of the group who made the work and added an additional layer to it — the languages you usually have to learn as a migrant.” Solh pauses. “It reflects the generation to come, instead of nostalgia. Sometimes the kids’ singing is accented, giving the languages a new life.”

These works are rooted in Solh’s childhood wartime experiences, reawakened by a spectacular reminder that — though it’s been more than three decades since the civil war was declared done — the country’s dysfunctions persist. Yet Solh’s language is securely lodged in the present, in the experience of mass global migration, and speaks with distinctly international accents.

Visitors to “Let’s Sleep” have read meaning into the work that the artist did not intend.

“At the entrance of the exhibition, there is a painting of a warplane. Two years back, shortly after the war started between Russia and Ukraine, I started hearing warplanes in the skies where I live. I’d hear them and I’d want to run away. People would be walking down the street normally while I was on the verge of a panic attack. I immediately started painting that warplane.

“When we opened in November, people saw the [warplane and pajamas] in light of what’s happening now in Gaza. They assumed I was specifically referencing Palestine, but of course, this project was planned months before.”

She pauses. “Once you grow up in war, war never leaves you. Unfortunately in our part of the world, war is again very present. It feels that the same history is repeating itself, but each time it’s worse, the trauma. The wounds barely close before a new war opens them again.

“Every child on this planet deserves peace. Every child deserves to be able to wear a pajama, to close their eyes and sleep safely.”

Foreigners Everywhere, the 60th Venice Biennale, runs April 20-Nov. 24, 2024.