A still from the video accompanying Zad Moultaka’s single-channel sound installation ‘Ejecta,’ 2023. (Credit: Zad Moultaka Studio)

BEIRUT — “The museum is still in crisis mode,” says Karina El Helou, director of Nicolas Sursock Museum. “Everyone here has been in this crisis mode for the last four years.”

After over two decades in Europe, Helou returned to Beirut in the fall of 2022. She inherited an institution redolent with heritage. Housed in a villa of an Ottoman Beirut merchant family, it is among the cultural landmarks to survive Lebanon’s long Civil War. Shut for renovation in 2008, Sursock was relaunched in 2015 as a state-of-the-art museum with five times the exhibition space of the original. It was helmed by a professional 30-strong team fronting a varied exhibition schedule, buoyed by a rich public program and driven by sustainable financing, anchored by funds from the municipality — drawn from a 5 percent tax issued on building permits.

Before taking the wheel at Sursock, Helou was best known locally for her work with Studiocur/art, the non-profit public art platform she created in Paris in 2015, with a focus on contemporary art and heritage. With Studiocur/art she curated a pair of large exhibitions in Lebanon. “The Silent Echo,” 2016, staged in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, peppered the Baalbeck Museum and the ruins of old Heliopolis with contemporary art. Mounted in collaboration with the Beirut Museum of Art — BeMA, 2018’s “Cycles of Collapsing Progress” used Tripoli’s Rashid Karami International Fair (designed by Oscar Niemeyer) and the Crusader Citadel as exhibition spaces.

Since 2019, Lebanon’s interminable collapse has undermined Sursock’s operating premises, and the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion caused substantial damage to the villa’s structure and works in its collection. In the wake of the blast, the museum’s international partners rallied to its aid and the damage has been repaired. Sursock is scheduled to reopen to the public in May with five new exhibitions of work by Lebanese modernist and contemporary artists.

Relaunching Sursock is a significant event in a scene badly depleted by the past four years or so. The challenges ahead are immense. Helou sat down with L’Orient Today to discuss the state of the ship and the course she’d like to chart.

Well-adorned and depleted

“The main challenge for next year is to keep this institution running,” Helou says. “We don’t have any more funding from the municipality for the next year, so no funds for the rest of the year. That’s the state of the ship,” she laughs. “It’s floating, but …”

It’s a pleasant Sunday afternoon and the museum’s cafe-gift shop — one of its principal means of fundraising these days — has hosted a family luncheon at Sursock’s esplanade. Staff members are impatiently tearing down tables, stacking chairs and hustling them off the premises.

“I was in a bit of a panic when I started,” she adds, blinking at the bustle around her. “I wasn’t here for COVID or the blast but you get used to the banks not working, to things not working generally, to business hours randomly changing.

“The strategy now is to create fundraising strategies — ”

Someplace, wood creaks and crashes loudly against wood.

“When I arrived, there was still a bit of money from the museum’s insurance [policy]. We withdrew the lollars [in the bank] — at a 15 percent rate,” she grimaces. “This is how we’re paying for things right now. It’s the last of the last money in the drawer.

“It’s heartbreaking. The museum had a strategy. Even if they didn’t get the money from the municipality, they had money in the banks, but that all went to lollars. They got 15 percent of what they deposited, like everyone in the country. Or most.”

She examines the leftover deserts a staff member donated to the interview.

“In the end we’re more a private museum than a public museum, but you feel the state actually doesn’t care. Nobody asks how the museum is functioning. This is one of the only public/private institutions that’s free, yet nobody asks, ‘How are you paying your bills?’ Everybody wants to see magic. ‘It’s working still. Oh, that’s great. Let’s take a selfie!’”

She smiles.

“In the end I’m quite happy to be here. I’m sure that we will make a great job. We’ve started inviting artists, and we’ve had a good turnout every time we’ve done a conference or screening. People want to see this institution come back.”

Helou appreciates that her predecessor Zeina Arida and her team accomplished most of the heavy lifting needed after the port blast.

“The Italian Agency for Development Cooperation and UNESCO Beirut and the French Ministry of Culture, and ALIPH [the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas] — they all participated in restoring and rehabilitating the museum,” she says. “We got help to restore the collection — three works from Pompidou, 40 works here with the Institut national du patrimoine. Thankfully, everything that was very heavy is already behind us.”

Structurally restored, the museum will reopen on a skeleton crew.

“We are the only modern art museum in Lebanon and we lack professionals,” she says. “The challenge now is to find specialists. Lebanese universities don’t really offer master’s degrees in art. We have a lot of researchers but, outside the commercial galleries, we don’t have enough cultural managers. We have fewer museum specialists, people who know how to work with collections. We have to see if we need to bring in someone from abroad to serve as collection conservator.

“We’ll see for the next year about a new team. For now we have two new people — one for communications and a new operations director working with me.

“We have this role to play in the region, I feel, and that’s important — to review the history, to write it in a more conscientious way. As survivors, we should give ourselves this mission at least, to write and publish some sort of history.”

Five new exhibitions

Sursock is scheduled to reopen on May 26 with a suite of exhibition openings running a gamut from Lebanese modernism to recent works from the country’s contemporary artists. Three shows draw upon work from the museum’s permanent collection.

“Je suis inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the National Canon,” curated by Natasha Gasparian and Ziad Kiblawi was devised to mark the museum’s 60th anniversary in 2021. The title is derived from an excoriating critique of the inaugural edition of Sursock’s Salons d’Automne — a signature show designed to highlight the work of the artists of the day.

“Jalal Khoury wrote that if you visit the Sursock museum today, you wouldn’t know that you’re in Beirut,” Helou smiles. “It was a critique of the museum’s not creating something that is typically Lebanese. These critiques accompanied many Salons d’Automne prize winners when the art scene was being formed in the ’60s and ’70s.

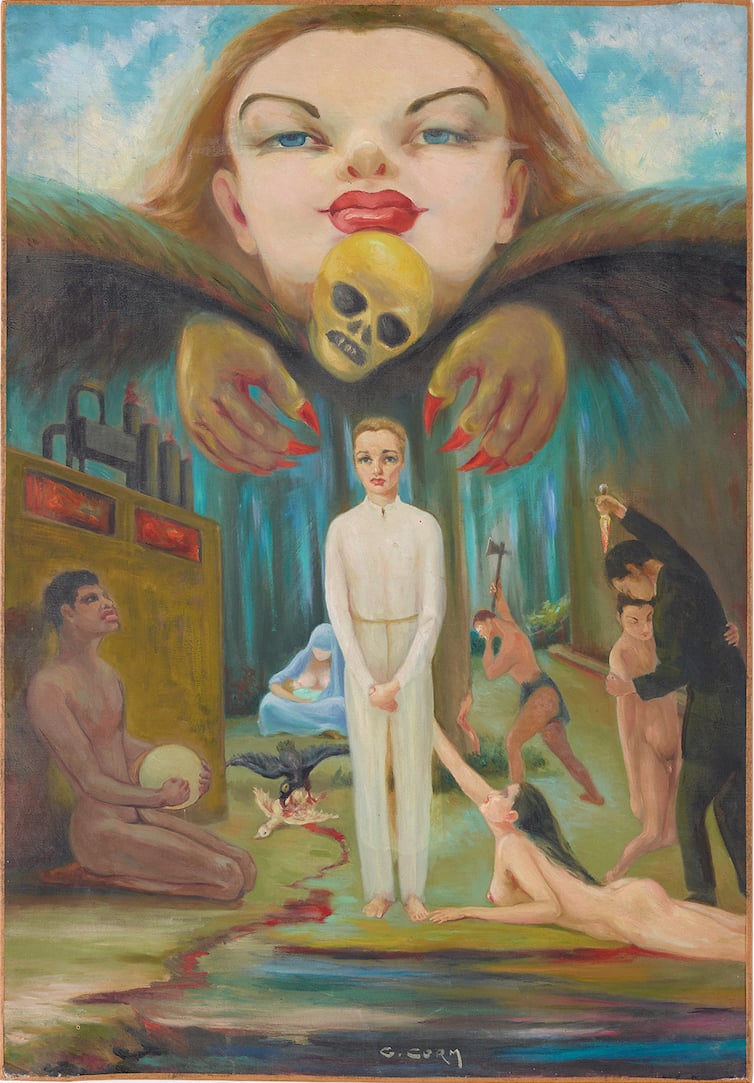

“Natasha’s exhibition is around this debate. In addition to artists exhibited in the salon, she includes artists that weren’t exhibited very often, or were rejected. There’s a section of the artists of the ’80s and ’90s who exhibited several times during the war that we never saw before. Then she proposed a coda, to understand the period not only based on the Salon d’Automne but to re-read the work of [renowned modernist] Georges Corm, for example, through his surrealist painting. It is really to escape this authoritative role that historians ascribed to the Salon d’Automne — that the prize winners were somehow the best artists of the time.”

‘Vision de cauchemar,’ undated, oil on canvas. Georges Corm’s surrealist piece is among the works on show in ‘Je suis inculte!’ (Credit: Courtesy of Sursock Museum Collection)

‘Vision de cauchemar,’ undated, oil on canvas. Georges Corm’s surrealist piece is among the works on show in ‘Je suis inculte!’ (Credit: Courtesy of Sursock Museum Collection)

Accompanying “Je suis inculte!” is “Beyond Ruptures — A Tentative Chronology,” curated by Helou with Ashraf Osman, an art historian affiliated with the Orient Institut Beirut.

“This is a timeline from 1952 to 2023. It’s comprised of three texts that make up a history of when the museum was shut and why, including its exhibitions and the social and political events of the time. For each period we also chose a work that represents a rupture, a creative or personal crisis, for an artist, or which reference political events of a given period, from Shafic Abboud to Nesrine Khodr.

“In its 62 years, the museum had to shut six times. It’s a reflection on how the museum completely merged with the city when it was destroyed, as well as on whether context influences art or not.”

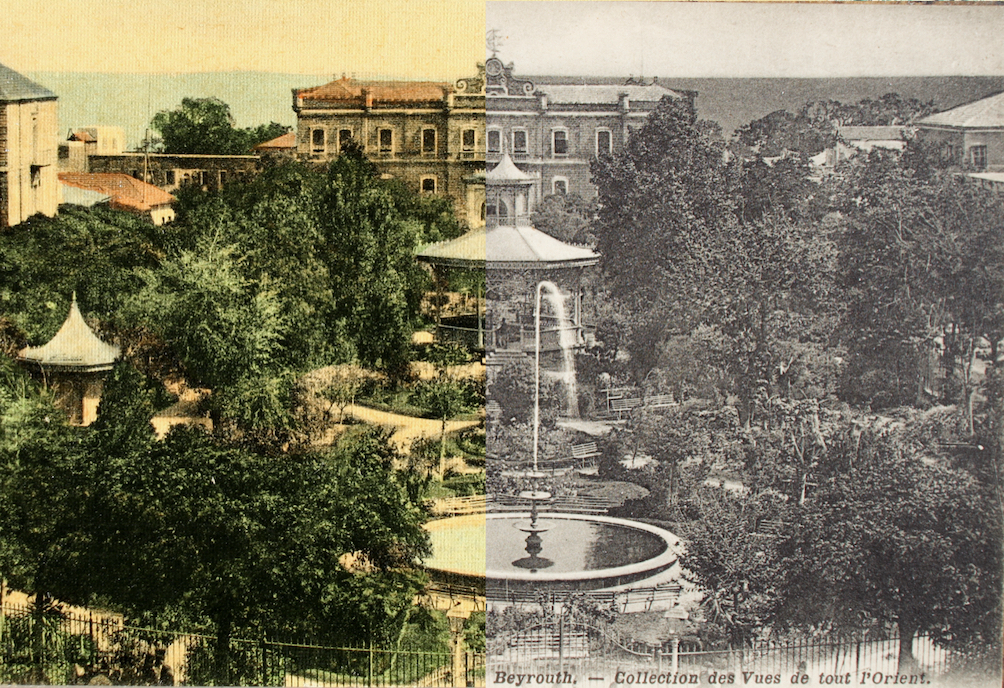

“Beirut Recollections,” curated by Helou and Pierre-Nicolas Bounakoff, is premised on the role that technology has played in the history of photography. Each generation has deployed new technologies to “improve” representation — from using watercolors to colorize black-and-white postcard images, to panoramas and stereoscopy.

In this show, works from the Debbas collection are placed in dialogue with “Reminiscence of a Moving City’s Many Stories,” a film by Iconen, a company that uses photogrammetry to create 3D images. The video on show is a three-minute excerpt of one UNESCO commissioned after the port blast, its 30,000 images stitched together to recreate a virtual tour of Beirut’s heritage buildings.

A postcard from the Fouad Debbas Collection showing an early effort to colorize a photographic image. (Credit: Courtesy Sursock Museum)

A postcard from the Fouad Debbas Collection showing an early effort to colorize a photographic image. (Credit: Courtesy Sursock Museum)

Sursock’s other two exhibitions swerve toward the contemporary. Twin Galleries will host “Earthly Praxis,” an exhibition of work by Marwa Arsanios, Ahmad Ghossein and Sabine Saba, curated by Susock’s Marie-Nour Hechaime.

The works on show include the fourth installment of Arsanios’ research-based project “Who Is Afraid of Ideology?” which uncovers layers of land transformation surrounding a now defunct quarry in the mountains of North Lebanon.

A still Marwa Arsanios’ ‘Who is Afraid of Ideology, 4,’ 2022. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier)

A still Marwa Arsanios’ ‘Who is Afraid of Ideology, 4,’ 2022. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Mor Charpentier)

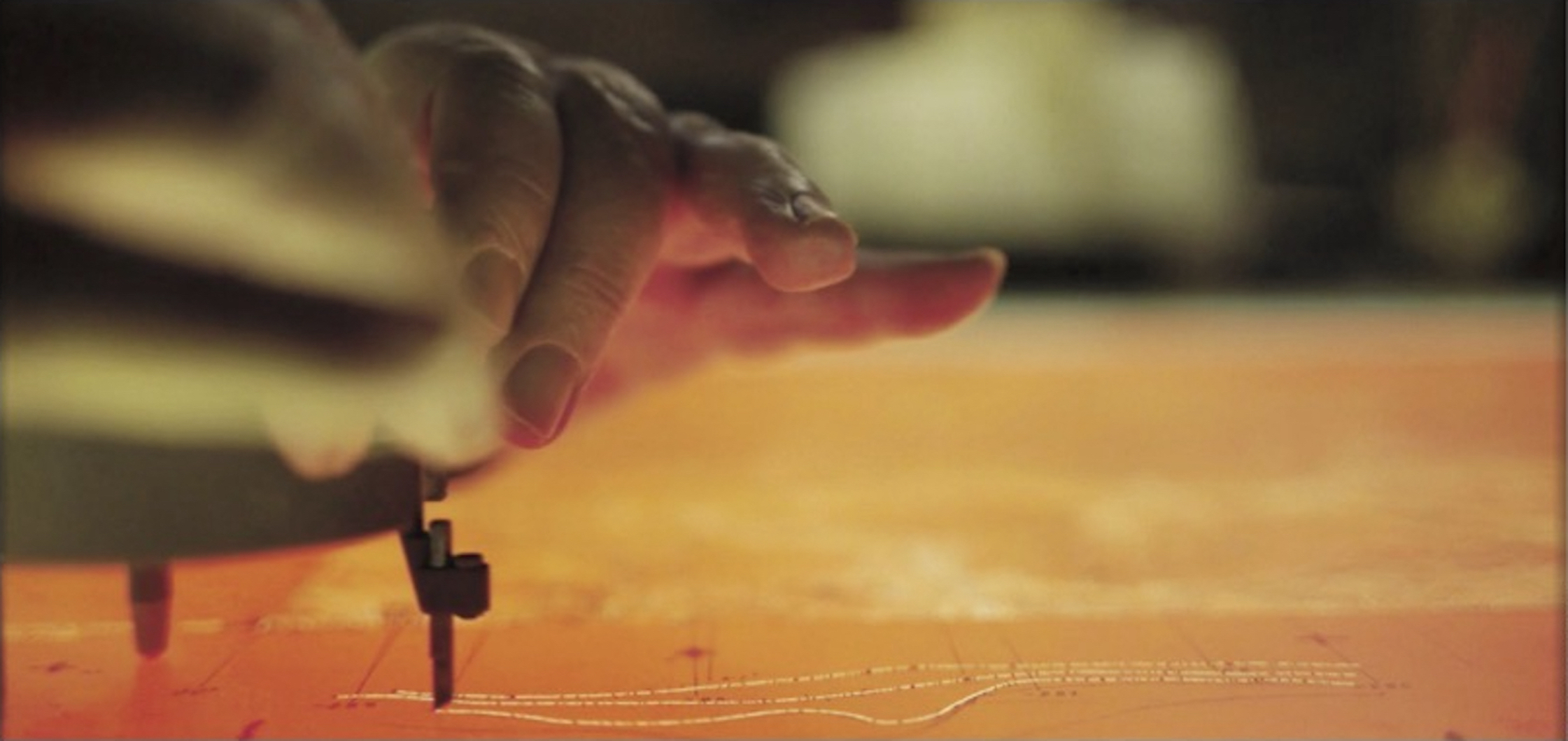

Ghossein’s works are interested in unregistered plots of land in southern Lebanon. His 16-minute video “The Last Cartographer in the Republic” is an interview with Mohammad Adeeb Khaled, the eponymous cartographer, who worked at the Directorate for Geographical Affairs from 1963 to 2006. Khaled’s voiceover describes the directorate’s workings — from aerial photos and terrestrial surveys, hand-etched maps and satellite imaging — as seasoned hands wield now-obsolete engraving tools to carve lines of elevation and shadow upon the bright orange surface of an extinct mapmaking media.

A still from Ahmad Ghossein’s ‘The Last Cartographer in the republic,’ 2017. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Marfa’ Gallery)

A still from Ahmad Ghossein’s ‘The Last Cartographer in the republic,’ 2017. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Marfa’ Gallery)

Saba’s autobiographical installation “Territorial Calendars” is an audiovisual work reflecting on land inheritance, one that underscores the struggles of inheritance when the individuals involved have drifted away from the locally conventional family structures.

Susock’s Special Exhibitions Hall will host “Ejecta,” a new work by Paris-based composer-cum-visual artist Zad Moultaka. The title is derived from the word for particles ejected from an active volcano.

The work is an immersive audio-visual installation which transforms the digital images of every artwork in the museum’s permanent collection into vibrating pixel-like fragments which move through various states to eventually cascade fluid-like through the frame.

“It is important to me that people feel that the museum is accessible,” Helou says. “There’s always this question — in which language do we speak? English, Arabic or French? If you don’t do it in French, people will complain. If you do it in Arabic, people complain.”

She chuckles.

“You must embrace the fact that we need a big translation budget.”

Sursock Museum will reopen to the public on May 26.