Abinader concentrates on the task at hand. (Credit: CH)

Her life has certainly not been sewn with white threads. It follows rather a long, quiet and transparent river lulled by prayer, silence and solitude in which she immerses herself, all day long, to be able to meditate, to work and to forget the outside world.

However, it is mostly with blue, sometimes burgundy, or black threads that Gilberte Abinader’s life is written. Her main enterprise entails embroidering initials on men’s shirts, usually on the heart side or cuffs.

Infinitely small, these two or three letters, which often display social status, are traced slowly, with steady hands, and unfailing eyesight now assisted by glasses.

“It’s normal at my age,” she says.

Abinader is 55 years old, with three sons aged 33, 31 and 27. She has “two daughters-in-law” and her third son has “a fiancée.” Her husband, formerly in the military, died in 2012.

Gilberte Abinader has been embroidering initials on shirts for over 30 years. (Credit: CH)

Gilberte Abinader has been embroidering initials on shirts for over 30 years. (Credit: CH)

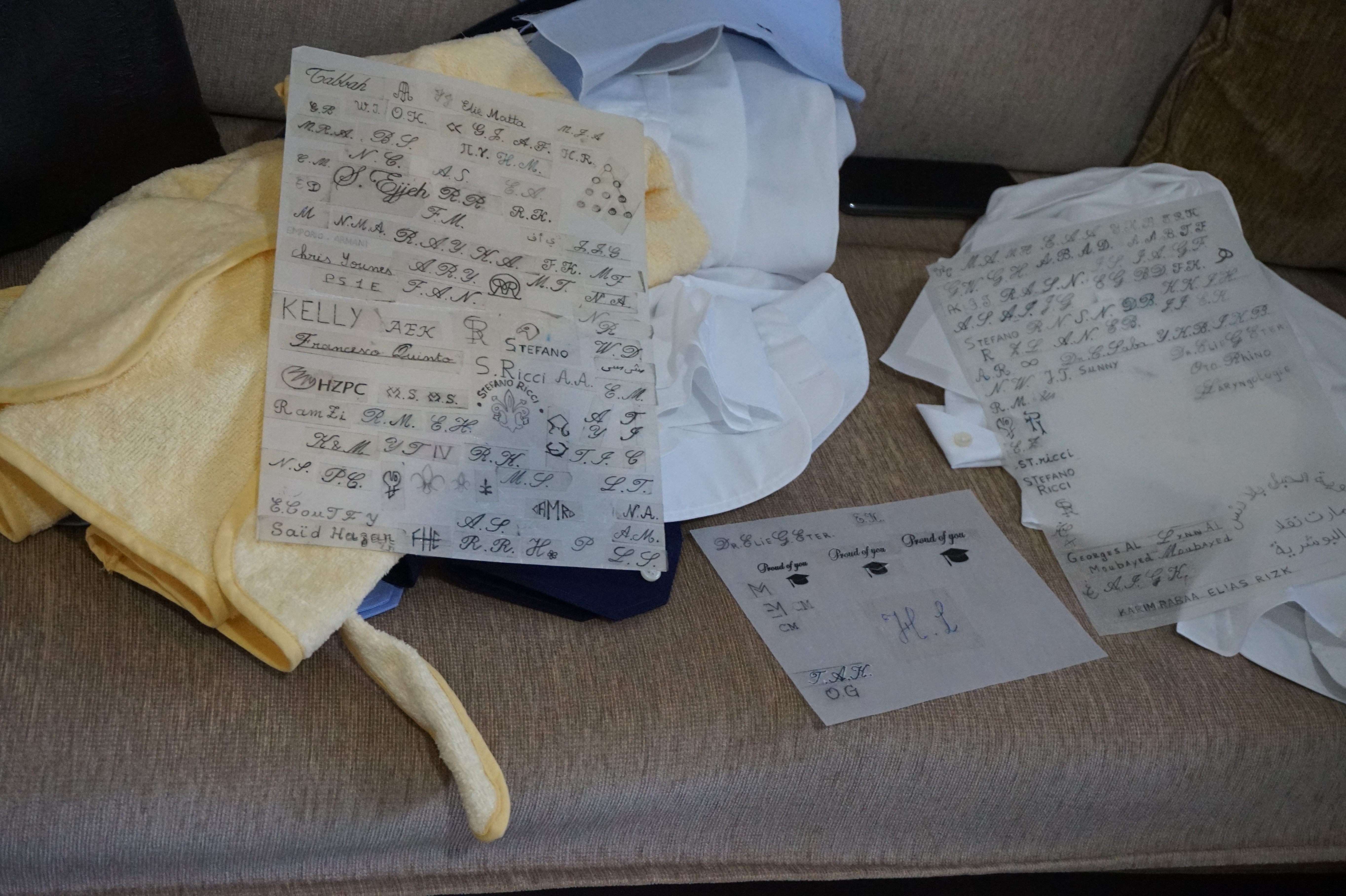

In this corner of the living room where she receives her customers, seamstresses and friends, the bulging nylon bags of shirts, sleeves, pieces of fabric, threads and butter paper sketches are laid gently, in a not-so-surprising order, on and around the sofa.

The elegant embroiderer wears a white dress with a large green flower in the center and a crucifix around her neck, as she sits in her discreet, improvised workshop that has something feminine, almost maternal, about it, even though Abinader mainly caters to male customers.

Text, drawings, themes for all occasions. (Credit: DR)

Text, drawings, themes for all occasions. (Credit: DR)

Miss Loris

It was “around 25 years ago, I do not remember precisely,” that Abinader learned this unusual calligraphy and sewed her first letters.

“My aunt on my mother’s side, Miss Loris Rustom, had a workshop in Tabaris,” Abinader recounts. She was still a student at Al Azarieh School when she first showed interest in Miss Lori’s work, shyly watching and helping her.

“She taught me everything. One day when she broke her hand, I was forced to take on the job entirely,” Abinader says.

Loris continued to work until the age of 93, “as long as her eyes were healthy, nothing could stop her,” the embroiderer adds.

Even the ties are personalized. (Credit: DR)

Even the ties are personalized. (Credit: DR)

The technique may seem simple; sewing two initials might look an easy thing to do, but “it is not something obvious,” Abinader says.

“Some letters were more complicated to trace, at the beginning. I hated the M, and the W. And then, when you have to embroider two same initials, AA, NN, for example, it is difficult to make them exactly the same. The error is immediately visible,” she explains.

Straight or italic, Abinader’s alphabet is sometimes accompanied by drawings depending on the occasion, whether a baptism, first communion, engagement or wedding. Other orders are for personalized gifts or liturgical fabrics.

Abinader is keen on responding to the needs of her direct clients, expatriates and dressmakers, who are her “main customers.”

“All custom tailors in Lebanon contact me and send me their instructions. And I execute,” she says.

Asorted typographies from which Gilberte Abinader draws inspiration in her work. (Credit: CH)

Asorted typographies from which Gilberte Abinader draws inspiration in her work. (Credit: CH)

Custom-made

To satisfy growing demand, and because at the time “the days were happy,” Abinader opened her workshop in Burj Hammoud in 2010.

“I worked on 30 to 40 shirts per day. We were young and there was plenty to do,” she says proudly and nostalgically.

Politicians, sports teams, individuals, priests, schools and of course men’s designers came to her shop.

“Everything was going well,” she says while serving a blackberry syrup, adding, “Try this, it is really good, you should have it.”

Abidnader goes on to say, “I execute any drawing to the desired size. I love this job; nothing seems difficult to me. I can spend entire days, even nights, as long as I have the energy.”

Abinader embroiders by hand, with particular attention to detail. (Credit: The Ready Hand)

Abinader embroiders by hand, with particular attention to detail. (Credit: The Ready Hand)

Seven years later, and especially “when the dollar started to climb,” she was forced to close her workshop and continue her work from home.

“The 1970s and ’80s fashion has gone into a slight decline, but it’s coming back. Even women are making orders, first for their husbands, then for themselves,” she says.

The space here is enough for her. It is as inconspicuous as it can be. The calmness soothes her.

Precisely and slowly, Abinader embroiders. (Credit: CH)

Precisely and slowly, Abinader embroiders. (Credit: CH)

“When I’m working, I’m happy, even if I’m exhausted. I forget everything. I put my phone on silent mode, I am focused, and I collect myself, I don’t see the problems anymore,” Abinader says.

In this exercise, this slow gesture that she repeats while remaining silent is somehow akin to prayer or therapy. She smiles looking down at her piece of fabric under the spotlight; she holds the thimble to her finger, the small scissors and threads are within reach.

To contact Gilberte Abinader : 70 02 13 88

Find these portraits on the Instagram page @thereadyhand

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.