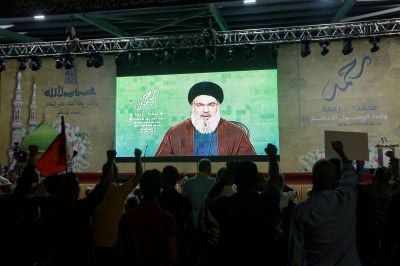

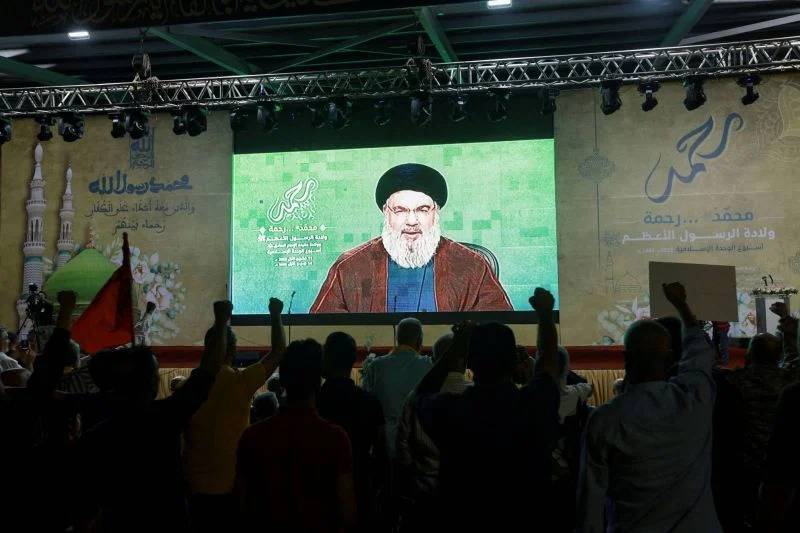

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah addresses his supporters on Tuesday, Oct. 11, 2022. (Credit: Aziz Taher/Reuters)

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah could have asked Lebanon to claim Line 29 as its maritime border with Israel. He did not.

He could have torpedoed the negotiations by making demands that are impossible for Israel to accept. He did not.

He could have targeted Israeli infrastructure militarily to prove the seriousness of his threats and to push Israel to make more concessions. Again, he did not.

With the maritime border demarcation issue between Lebanon and Israel, Nasrallah was playing with fire.

But this strategy was not meant to prevent the deal from going through — something that would not have been possible without his green light anyway.

Nasrallah’s strategy, however, was intended to prepare his audience for the unthinkable and the forbidden: an agreement with the “enemy” endorsed by the pro-Iranian party.

After more than 10 years of dispute, Lebanon and Israel seem to have finally reached an agreement on the delimitation of their maritime border.

But on Tuesday night, Nasrallah appeared to want to mitigate the significance of the event.

“We are waiting for the moment when the delegations (of both countries) will enter Naqoura to sign so that we can say that an agreement has been reached,” he said in a televised speech.

From his position, the Hezbollah leader cannot openly congratulate himself on the conclusion of a deal with the “Zionist enemy.”

It is more convenient for him to “hide” behind the state — whose sovereignty he nominally recognizes for once — by assuring that it is the state that ultimately makes the final decision on the deal.

On the one hand, Hezbollah does not want to give the impression that it is at the forefront of this matter, which would have caused it a series of troubles and ideological incoherence.

On the other hand, the party has started to disseminate the idea, through its communication channels, that the agreement, and more precisely the Israeli concessions, were the result of the fact that it was involved in the issue, going as far as to present the deal as a “victory” it managed to pull off.

The party has repeatedly threatened to target the offshore Karish gas field if Lebanon does not get its “economic rights.”

Did it succeed in making Israel bend? Have Hezbollah’s threats played in favor of Lebanon? It is difficult to know the answer.

Hezbollah’s ultimatum of targeting Karish may have encouraged Israel to give in more and faster than it would have liked in order to begin extracting gas from the field.

It was more difficult for Israel to try to gain time under these conditions.

But Israel already seemed inclined, even before Hezbollah’s threats, to accept that Line 23 delimits its border with Lebanon, provided that Beirut recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the Karish field.

Hezbollah’s outbidding, which could have cost Lebanon a devastating war, was mainly aimed at preparing the public opinion, and in particular its popular base, for an agreement based on Line 23, knowing that Lebanon could have claimed Line 29 under international law.

An economic calculation

Why did Hezbollah give the green light to such a deal?

The economic and financial situation gripping Lebanon is certainly a decisive factor.

Even with Iranian support and despite the services it offers to its partisans and followers, Hezbollah alone cannot respond to a crisis of this scale.

The party’s popular base is suffering, as is the rest of the population.

Hezbollah may have calculated that potential gas and oil money from the offshore sites — valued by Israel at $3 billion in total — will allow it to stabilize the country and replace the rentier economy with an oil-based economy.

The fact that the conclusion of the framework agreement, which re-launched the negotiations, was announced by Hezbollah’s main ally Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri a year after the crisis broke out, is far from insignificant.

Lebanon, however, still does not know how much the Qana field could contain in terms of hydrocarbons.

It is possible that the agreement will not bring it any economic benefit and in the best-case scenario, it will take several years to reap the first rewards.

Then why did Hezbollah take this risk?

Was it a desire on the part of Iran to make a gesture to the United States?

There is no evidence to confirm this hypothesis or simply to understand the exact role of Iran in this matter.

It seems very unlikely that Hezbollah could have taken such a strategic decision without the green light from its Iranian patron.

It also seems clear that the deal on the maritime border could not have been concluded at a time of great tension between Iran and the American-Israeli tandem.

In other words, there was a window of opportunity to make the agreement a reality before the last chances of reviving the nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1 countries faded.

Did the Islamic Republic make a regional or simple calculation at the level of Lebanon, taking into account the delicate context in which Hezbollah finds itself, increasingly contested on the internal scene? This is not clear, for the moment.

What is clear, however, is that the agreement confirms the transformation of Hezbollah that began with the withdrawal of Syrian troops in 2005 and the war against Israel a year later, in the summer of 2006.

It confirms that the party’s priority is to consolidate its position in Lebanon and to consolidate the Iranian axis in the Middle East.

The anti-Israeli rhetoric, which allows it to attract supporters beyond its confessional base, will remain central in the party’s communication.

Hezbollah will also continue to claim the Shebaa farms (on the borders of Syria and Israel) in order to justify its military arsenal.

Officially, the Hezbollah-led “resistance” will always aim to “liberate Palestine” and will not tolerate any compromise with the “enemy.”

In reality, however, the two sides have not clashed for 16 years, except for a few scuffles.

Hezbollah could have created a “Shebaa on the sea” by claiming Line 29.

Instead, it has chosen the path of an agreement that makes the possibility of another war more unlikely, especially if Lebanon becomes an oil- and gas-exporting country.

In a way, the deal changes the rules of the game, since it implies a minimum of cooperation, even indirect, between Israel and Lebanon.

It is not a question of normalization.

Officially, this is not even the beginning of a process in that sense. But the agreement does lay the groundwork for peace between the two countries, even if it may never materialize.

In this sense, Hezbollah appears to emulate the attitude of the Syrian government toward Israel after the 1973 armistice negotiated by Kissinger.

The Syrian-Israeli border has been stable for decades, and only the outbreak of the Syrian civil war has challenged this fact.

However, the late Syrian President Hafez al-Assad, and later his son Bashar, have always used and abused very hostile rhetoric towards Israel, using the Palestinian cause to make people forget their policies in Syria and Lebanon, including toward the Palestinians.

Hafez al-Assad theorized about this suspended conflict by claiming that he would take action once the strategic balance between the two states had been restored — in other words never.

Hezbollah seems to be following a similar logic.

It needs the Israeli enemy to “cover” its other actions but is no longer interested, in the short and medium term, in waging a new war against it.

The Lebanese-Israeli border could be stabilized in the long term. This is what could give the maritime border agreement its historical significance.

Gas and oil, the Karish and Qana fields, or Lines 1, 23 and 29, are secondary here.

The main thing is the geopolitical dimension of the deal, which consolidates an equation dear to the Assad regime: Neither war nor peace.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.