Traffic island along Pasteur Street in Gemmayzeh leading to Mar Mikhael. Bride of Beirut sculpture with Memorial of Gratitude sculpture behind it on Sept 29, 2022. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — In the capital’s busy Gemmayzeh neighborhood, two sculptures stand amid shards of glass and garbage on a narrow traffic island on Pasteur Street that divides two parallel roads leading away from Mar Mikhael.

Frustrated drivers try to park their cars alongside the island’s curbs. On the sidewalk nearby, hospital staff stand outside taking cigarette breaks but can’t find any place to sit.

The site sits just 675 meters away from the epicenter of the Aug. 4, 2020 Beirut port blast, and currently holds two statues: One erected in 2015 to mark the centennial of the start of the Armenian genocide and the other being a recent installation in the wake of the blast.

The latter, a statue of a woman, titled the Bride of Beirut and intentionally surrounded by shards of glass from Aug. 4, has stirred debate in the area over the best way to memorialize the blast.

Since the devastating explosions many people have accused the Lebanese government of trying to spatially erase any traces of the blast, citing inaction over a weeks long fire at the port that eventually fully felled half of its explosion-damaged grain silos.

Meanwhile, others have criticized memorials imposed from above as state-sanctioned objects like architect Nadim Karam’s “The Gesture” sculpture built inside the port out of scrap metal from destroyed warehouses.

Aside from that, critics say statues, on their own, fail to engage the public as deeply as other memorials do. Many cite as a successthe Samir Kassir Square, dedicated in honor of the Lebanese journalist who was assassinated in 2005, which includes both a statue of the Kassir and a shaded water feature with benches around it

‘It’s not that we want to forget’

More than a year ago, environmental activist Samer El Khoury was cycling through Gemmayzeh and passed by what he described as “an eyesore.”

The sight of glass on the traffic island, placed there as part of the memorial statue, evoked terrible memories of Aug. 4.

The shards of glass are part of the Bride of Beirut installation. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

The shards of glass are part of the Bride of Beirut installation. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

El Khoury remembers the day vividly: “I was actually there when the blast occurred, and was near Pasteur Street. I still remember how it was filled with blood and screams and rubbles of pain.”

The sight of glass shards was not pleasing.

“I was just cycling and I saw this whole thing then I paused and I'm like, it’s quite gory, and it’s reminding me of the whole blast. It's not that we want to forget what happened but there are different ways of remembering or commemorating, and that's not it,” El Khoury recounted.

Having worked on reforestation and public space projects before, he and two friends decided to take matters into their own hands. They removed what glass shards they could in order to clear space on the traffic island and plant the ground. To enlist the help of others, they made a video of volunteers working on the traffic island.

“So, then I started contacting a network of people because I also volunteer in reforestation, making public spaces,” he explained.

After posting a video on social media to solicit help, he found that many other people echoed his frustration and approached him to help clean the site.

Samer El Khoury and friend removing glass and planting the traffic island. (Photo courtesy of Samer El Khoury)

Samer El Khoury and friend removing glass and planting the traffic island. (Photo courtesy of Samer El Khoury)

The social media campaign even reached the sculptor artist himself, who contacted El Khoury.

Architect Hani Tabsharany, who made the sculpture and arranged the surrounding pile of glass shards in the wake of the blast, told L’Orient Today he was inspired to make the artwork after he mistakenly thought a loved one had died in the blast.

“For 10 minutes we didn't know what was happening because there was no cellular connection,” Tabsharany says. He says he aimed to personify the city as a “bride,” adding the glass to remind viewers “of how bad that day was.” His brother, Habib, later added a series of vertical concrete slabs engraved with the blast victims’ names.

Tabsharany adds that he didn’t intend any harm in placing the glass around his statue, his intention was for the monument to serve as a daily memorial for visitors to remember the tragedy, and commends El Khoury’s efforts to clean up the shards from the traffic island.

El Khoury pointed out that the glass shards could be dangerous to people in the neighborhood. “Small pieces of glass can be blown away with the wind and eventually end up in some houses. The whole thing is not okay.”

Jakob Frasch, a long-time Gemmayzeh resident, told L’Orient Today he hadn’t even realized the shards were part of the art: “It's hard to tell the glass has been put there deliberately.”

Potential public plaza?

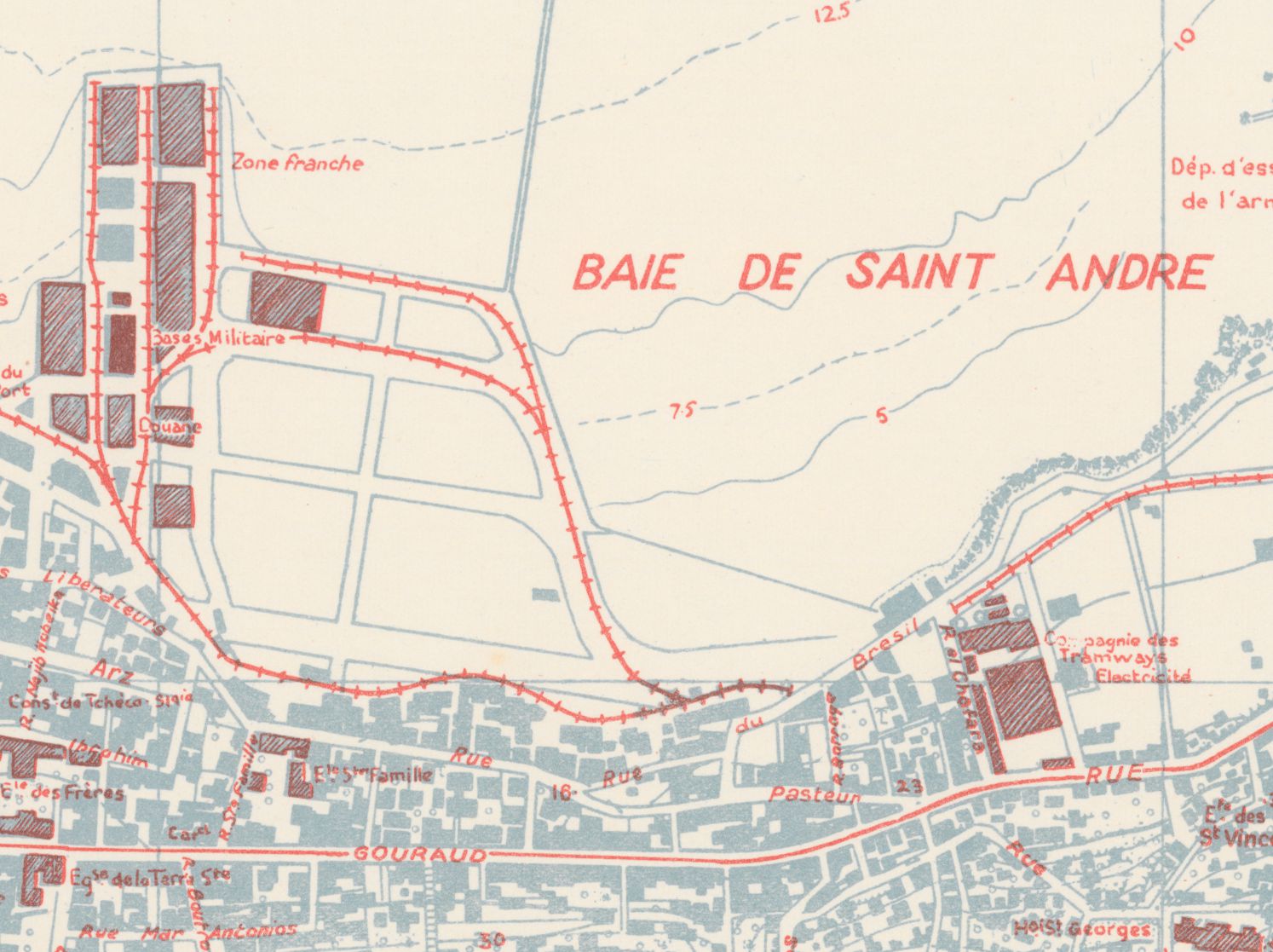

The 220-square-meter traffic island sits along an intersection of a historical route. Pasteur Street is one of the oldest in Beirut, built in the 1830s to connect the old city of Beirut to the seaside quarantine for incoming travelers, today’s Karantina neighborhood.

Originally Nahr Ibrahim Street, it was renamed after Louis Pasteur during the French mandate in the 1930s. The road was widened in the 1950s, with a traffic island carved out of a triangular lot deemed too small for constructing any buildings. Aerial photos from the 1940s show the lot was once part of a lush garden.

Originally Nahr Ibrahim Street, it was renamed after Louis Pasteur during the French mandate in the 1930s. From the 1941 Town Plan of Beyrouth by British Army (Creative Commons)

Originally Nahr Ibrahim Street, it was renamed after Louis Pasteur during the French mandate in the 1930s. From the 1941 Town Plan of Beyrouth by British Army (Creative Commons)

The street once bordered the sea before one of the terminals in the Beirut port was closed in 1935 and later expanded in the 1960s.

The expanded terminal was the one that held the fateful Warehouse 12, which contained the ammonium nitrate that ignited on Aug. 4, 2020. This made the area around the traffic circle vulnerable once the chemicals exploded.

The spot can be easily missed, but has potential. One plan, which El Khoury and other activists proposed and municipal authorities have approved, includes cleaning the traffic island, planting it and otherwise keeping the site as is.

Another, more ambitious plan involves expanding the island to join the adjacent sidewalk by removing the southern part of the road.

The additional space recovered from removing the road and marrying the existing sidewalk with the island would effectively create a public plaza with enough space to add benches, trees and a bike rack.

Though a small step, the idea could help fill the gap in public space in Beirut. The city notoriously has three times more parking lots than parks.

Benches in the proposed public plaza could also address the area's urban furniture gap.

Anis Germany, a doctor and former medical resident at the nearby Rosary Sisters Hospital, said that aside from the concrete road blocks, he use to struggle to find places to sit while on his cigarette breaks.

“There weren't many options, either sit on the curb of the sidewalk or go all the way to St. Nicolas Stairs and sit there.” Germany says that though he wasn’t in the neighborhood at the time of the blast, he helped treat victims at another Beirut hospital.

Frasch also lamented the lack of free public space in the area beyond restaurant seating or parking for vehicles. “In its current state, this area is not inviting at all. It would need to be transformed, primarily by blocking off a considerable space for cars, [making it into] a pedestrian only area.”

“I think benches help upgrade public space if they are found in a location where residents would like to spend time,” Frasch said.

El Khoury said he and others “reached out to key stakeholders who work in reforestation,” in order to clean the site and plan a potential mini-park.

“After 13 months of back and forth meetings, we finally got the approval from the municipality of Beirut for the plans,” El Khoury says. Even better, authorities agreed on the activists’ second plan: to extend the traffic island into the adjacent street, creating a public plaza.

“We still haven’t agreed on the final plan, but it’s in the works,” he adds.

For Germany, the doctor who helped treat blast victims, memorials such as those commemorating the Aug. 4 blast should “serve a public function.”

“They’re a vital part of a city and allow people access and to interact in the city,” he says. “Commemoration should be with art. But I don’t see why we should choose one or the other.”