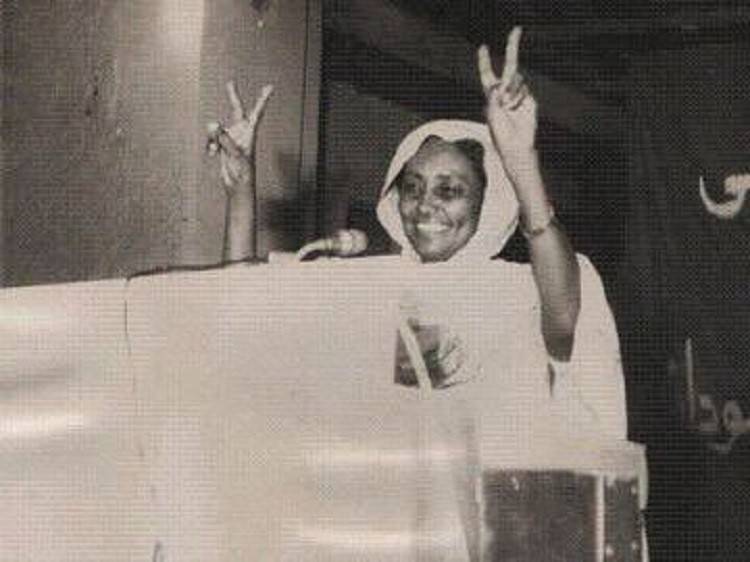

Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim, a Sudanese feminist who advocated for social justice and political rights. Photo: Wikicommons

On May 25, 1969, the Sudanese capital was boiling. A group of officers, led by Colonel Gaafar Muhammad Nimeiry, orchestrated a coup in Khartoum and overthrew the coalition government of Prime Minister Muhammad Ahmad Mahgoub. The country fell back into authoritarianism after five years of civilian rule.

In order to consolidate his power, Nimeiry sought to put on the costume of a progressive leader, one who supports women’s and workers’ rights. To do so, he had to attract prominent figures. Was this in order to control them better or to consolidate his prestige? A little of both.

One of his main targets was a seasoned women’s right campaigner: Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim, the first woman in Sudan’s history to be elected to Parliament under the previous regime. Since she was young, she boldly engaged in the tumultuous tides of the century.

One day, she received a call unlike any other. The First Lady was on the line, and the presidential couple wanted to invite her to lunch. Although wary, Ibrahim graciously accepted. In a deceptively warm atmosphere, the dictator revealed his plans: he intended to appoint her minister of women and social affairs. She did not agree with his flattery. Ibrahim refused to accept — the minister of women, she said, must be chosen by women themselves.

She recounted this incident in 200 to Rawan Damen, an al-Jazeera television journalist. In front of the camera, dressed in a traditional toub in yellow, purple and white floral print, Ibrahim, in her 70s, described Nimeiry’s fury.

“He struck the table with such a blow that the plates flew into the air!” she recalled. He apparently felt insulted. Shortly before, he had spoken with Ibrahim’s husband, the trade unionist Alshafie Ahmed Alshiekh. The president also had a big plan for him: to be appointed minister of labor. Alshiekh’s response was scathing. For him too, it was up to the workers and employees to choose their representative.

The couple paid dearly for their political stances at the time. In 1971, Nimeiry’ s former communist allies tried to overthrow him. A counter-coup quickly brought him back to power.

Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim in the late 1960s. Wikicommons.

Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim in the late 1960s. Wikicommons.

Although Alshiekh did not take part in the plan, he was tortured and executed as part of a large-scale purge. As for Ibrahim, she lived her life under strict surveillance and was regularly thrown behind bars.

Some 36 years later, she shared her great pain with the journalist who interviewed her. After she lost her husband, she swore before God that she would never get married again and that she will raise her son — who was two years old at the time — in a way that would make his father proud.

Not a copy

Fatima Ibrahim cultivated this fighting spirit since she was a child. It all began in the late 1940s at Omdurman School. In this first secondary school for girls, the British director reportedly swapped science for English and housekeeping. Sudanese teenage girls — she believed — need no other education. This decision was quite symptomatic of the era. Since 1899, the country has been under the yoke of an Anglo-Egyptian condominium. In practice, however, London had the final say.

The school walls obviously did not resist the anti-colonial fury. As a teenager, Ibrahim already espoused the cause and refused the fate that was being imposed on her. After having launched a student newspaper — Elra'edda (Arabic for the pioneers), critical of the British occupation — she organized a strike in order for the canceled courses to be taught again.

In the same vein, she set up the Intellectual Women's Association to oppose London’s policy of restricting the role of women in society. It was a bold step that she owed in part to her heritage. While her date of birth is not confirmed — ranging between 1929 and 1934, according to sources — biographical information matches on one point: the role of her family in her career.

Her mother oftentimes lectured her to stop looking at herself in the mirror. “Your beauty does not come from your hair, nor your beautiful face, but from what is in your mind,” she often said. “Fill it with knowledge.”

Her father, however, prevented her from pursuing university studies. It is a difficult attitude to understand from a man who considered his daughters’ education sacred. But it did not matter. The loss motivated Ibrahim to found the Sudanese Women's Union (SWU) in 1952, which echoed loudly. Influenced by her brother, she also joined the Communist Party in 1954.

“Our first demand was focused on women’s political rights, because we thought — rightly — that everything arises from there,” Ibrahim told L’Humanité, the French daily, in 1994.

“Our demand was rejected in the name of the Quran. So, we decided to learn about Islam to show the fundamentalists that this religion does not involve exploiting women," she added.

Throughout her life, Ibrahim was keen to firmly establish her struggle in the local context of her country, defending the concept that women’s emancipation does not mean “becoming another copy of the Western woman.”

Ibrahim stood at the forefront during the October 1964 revolution against the military regime of Ibrahim Abboud. Through the SWU, she mobilized her fellow women citizens in the street to put pressure on the tyrant. He surrendered to their demand. Elected a member of Parliament, Ibrahim worked hard to make significant headway.

The result of her efforts: on the eve of Nimeiry’s 1969 coup d'état, Sudanese women closed the gender pay gap, gained better access to higher education and the right to enter all professional fields.

Holy war

However, the SWU was banned by Nimeiry in 1971 and continued its work secretly. In 1983, Nimeiry imposed the Sharia law throughout the country, which became the starting point of a 22-year war between Sudan’s Muslim north and the predominantly Christian south.

This sinister torch was carried on by Omar al-Bashir in 1989, once the civilian rule (86-89) ended and the military-Islamist regime was established.

Faced with this fanaticism, Ibrahim was outraged. “It is a holy war for this Islamist regime,” she denounced in 1996 in the New Internationalist. “The southern people, since they are Christians, are called pagans. Women are raped routinely because this is seen as a way of putting more Islamic babies into the world. They are flogged for cultural practices like brewing beer; afterwards, the money they make from selling it is confiscated.”

In exile in London since 1990, she tirelessly continued her struggle and founded a branch of the SWU in the British capital. She had to wait until 2005 and the conclusion of an agreement between the National Democratic Alliance — an opposition coalition to Bashir’s regime — and the government to finally return.

Two years later, in 2007, she retired from politics. “Now is the time to hand over the banner to the youth,” she said in the 1996 interview. There were, however, some misunderstandings about the new generations.

Ibrahim did not always grasp the importance placed on individual freedoms by a more recent feminist rhetoric in Sudan, which had been devastated by war and poverty. “What priority can sexual choice have in the eyes of a woman whose child is starving in her own arms?” she reportedly asked.

Ibrahim, who died in London in August 2017, did not live to see the mass uprising of December 2018 and the overthrow of Bashir. Neither did she have the time to see women’s involvement in the movement — according to some estimates, women were more than 70 percent of the protesters.

But her legacy is alive more than ever. While the country is now sinking into a political and economic crisis, while the military is on the lookout, the young guard is watching.

To learn more about Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim:

El-Gizouli, Magdi, Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim (1933-2017): Emancipation as a craft, StillSudan blogspot, 23 August 2017.

This article was originally published in French at L'Orient-Le Jour. Translated by Joelle El Khouri.