A picture taken on Jan. 17, 2021 showing Beirut's deserted downtown district, known to many as Solidere, because the company rebuilt the area. (AFP file photo)

BEIRUT — Some $121,900: that’s how much $10,000 invested in Class A shares of the reconstruction and development company Solidere on Nov. 1, 2019, is worth today.

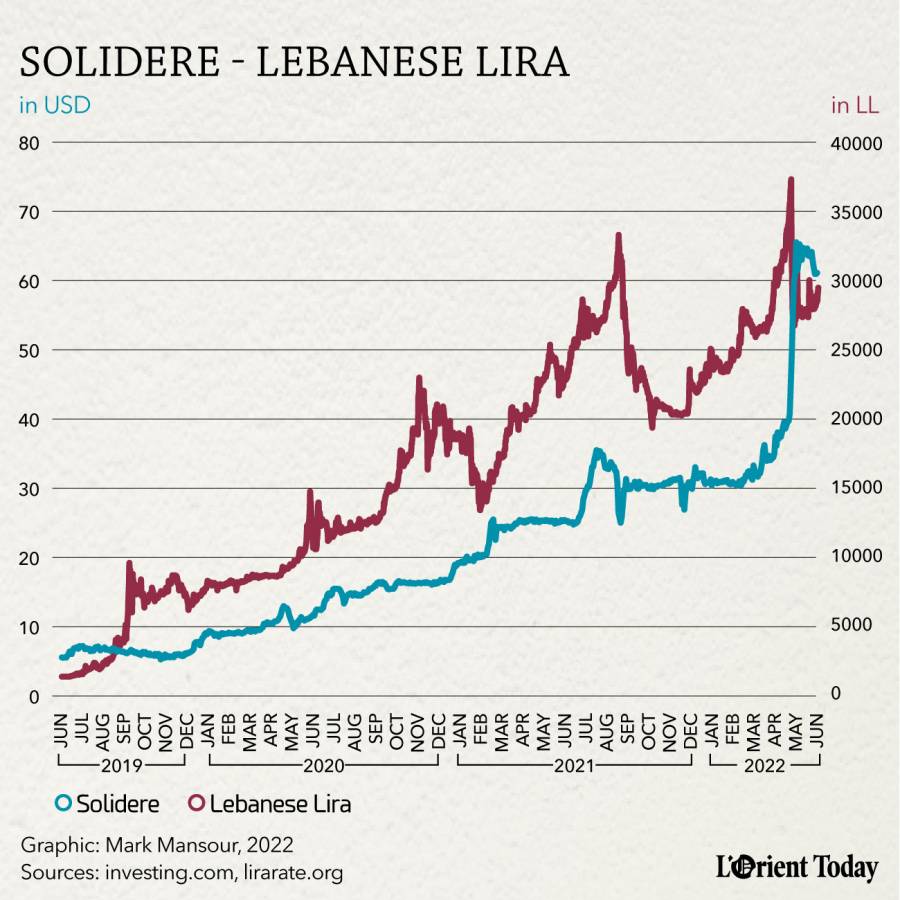

The performance of Solidere’s shares, a staggering increase of 1,119 percent, stands in stark contrast to the 60 percent contraction in the economy and the $72 billion hole in the financial sector.

Even though the $121,900 is in “lollars” — the term coined for dollars trapped in the banking system that cannot be withdrawn at their full pre-crisis value — it still amounts to $15,847 when converted to “fresh dollars” at 13 percent (the market rate set by money exchangers to convert lollar deposits into fresh US dollar banknotes), a hefty profit considering the crisis.

Amid the ongoing crash of the Lebanese lira, the public’s distrust of banks and uncertainty around the government's economic plan, an increasing number of investors have taken refuge in shares of the controversial real estate company.

Initially, Solidere’s name was associated with late Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s neoliberal economic plans for the reconstruction of postwar Lebanon. Hariri’s plan drew heavy criticisms for its use of forced evictions and property expropriation. More recently Solidere became the center stage for October 2019 protests and a lynchpin of all criticisms of the politico-economic policies that led to the economic ruin of the country.

The company’s present-day board of directors is also composed of some controversial figures, including Raja Salameh, the brother of central bank chief Riad Salameh, who is currently charged with illicit embezzlement. Bankers connected to SGBL bank, and its chairman Antoun Sehnaoui, also have seats on the board. SGBL is currently under investigation for breach of trust and fraud against depositors as well as misuse of public funds.

However, history aside, with the economy in shambles and the banking sector in trouble, investors have turned to Solidere’s shares as a means to salvage whatever was left of their shrinking wealth.

Real assets are typically considered a safe haven during periods of high inflation, currency depreciation and when trust in government is running low.

Faysal Barbir, director at FFA Private Bank, said “the [Solidere] shares acted as a store of value for investors who had lost confidence in the banking sector and wanted to protect what was left of their money” after they had “rushed to buy all kind of movable goods which disappeared first, then moved to apartments, land and listed equities.”

The existence of multiple currency rates further damaged trust and derailed the proper functioning of the economy.

The central bank’s strategy since the onset of the crisis was to reduce the size of foreign currency deposits in the banking sector and limit its exposure. So, it linked all the dollars in the system to the Lebanese lira.

In April 2020 the central bank set the conversion rate of LL3,900 per lollar but later in December of that same year, increased it to LL8,000, when the lira dropped below LL25,000 to the US dollar in the parallel market

Linking the lollar to the lira is one of the main drivers behind the success of Solidere shares. Solidere, a proxy for real assets — valued in fresh US dollars — is priced in lollars, a proxy for the lira, so this pricing mismatch meant that when the lira dropped, the share price increased to reflect the new exchange rate.

Barbir added that Solidere was the only viable option. What this means is that it was not Solidere’s fundamentals or its business model that attracted investors, but the fact that it is the only game in town that can offer daily liquidity with minimum ticket size.

If Lebanon had a deep and diversified equity market, then other companies in different economic sectors would also have benefited from the inflow of trapped deposits fleeing banks. But given the current market composition, the decision was split between investing in Solidere or one of the banks, and most Lebanese knew the banks were already bankrupt.

The trade was also a bargain for investors. They were paying in lollars – what has become lira, thanks to the central bank – for a claim on the company’s real estate portfolio in the heart of Beirut, as well as its 39 percent stake in Solidere International PLC with operations in the UAE and KSA.

Solidere representatives could not be reached for comment for this article.

As the lira lost ground, hitting an all-time low of LL37,700 against the US dollar in late May 2022, Solidere shares rose steadily from $5 to $60.95.

“It is pretty straightforward — just compare the return on Solidere shares to the 87 percent loss on deposits – money exchangers are buying lollar checks for 13 cents per lollar,” said an investment advisor who asked to remain anonymous due to his bank’s policy against talking to the media. “Even real estate prices are down across the country by 30, 40 percent or more, there is basically no demand.”

For depositors seeking to safeguard their funds, holding Solidere shares over the last 30 months would have not only preserved the value of the original deposit but would have generated a double-digit profit.

What could change: The government’s economic recovery plan

On May 20, Prime Minister Najib Mikati’s government met one final time before it got relegated to a caretaker status. Among the many last-minute decisions it took on that day was the approval of the long-awaited and controversial economic recovery plan, which aimed to write down $60 billion in deposits while at the same time protecting small depositors.

The revelation that the government is looking to write off $60 billion of foreign currency deposits has sparked a new round of speculation among investors. They question whether Solidere’s performance could continue and whether the shares could still hedge against the haircut, the lirafication (converting foreign currency deposits into lira) and the bail-in (exchanging deposits into bank shares) if the government plan is actually implemented.

The shares closed yesterday at $60.95, against $33.99 on Apr.19 when the government’s economic recovery plan was first leaked, an increase of 79.32 percent.

The document, as signed on that day, did not state an exact figure up to which deposits would be guaranteed, but it set March 31 as the cutoff date for the guarantee to apply, and any change in the balance beyond that date would not be covered.

Mikati and Deputy Prime Minister Saade Chami, in later speeches, confirmed that the guarantee will stand at $100,000 per account.

Balances above the $100,000 limit will either be converted into shares in banks, partially written off and partially converted to Lebanese lira at a different rate than that of the parallel market.

Consequently, depositors, in addition to having to reckon with the loss of their deposits, have also to worry about the printing of large amounts of lira. More lira in circulation means a lower value against the US dollar, higher inflation, and weaker purchasing power.

Another risk they have to contend with is the possibility of their bank going under. The government plan makes a distinction between an insolvent bank that should be liquidated or merged and a solvent one. No details have been given as to the fate of the deposits or the bail in if the bank is deemed insolvent, except that the $100,000 guarantee will cease to apply.

What is certain is that when the banking sector is restructured and the distribution of losses is finalized, lollars will cease to exist. The residual deposits will be repriced in actual dollars. The series of circulars issued by BDL related to deposits, such as 151 the 158 and the 161, will be replaced with a central capital control law, which in its latest draft iteration would allow for $1,000 in monthly withdrawals, either in US dollar banknotes, in lira or in a mix of both.

The restructuring will also lead to the repricing of Solidere shares from lollars to fresh dollars. However, there is disagreement among experts as to the value of the shares once the restructuring is complete.

A source at the Beirut Stock Exchange told L’Orient Today that, operationally speaking, the exchange can manage the smooth transition to fresh dollar pricing from lollar pricing. The source explained that once the government begins implementing its plan, the exchange will then notify its members of the new trading policies. The source added that prices will be determined through supply and demand and there is no knowing where the shares could end up trading.

“The shares lost 90% between 2008 and 2019, the company is a black hole and mismanaged,” the anonymous investment advisor said.

“The crisis was a blessing in disguise for the company,” he said. After the financial sector restructuring, he predicted, “The shares will go back to $5 or $6 a share, where they were trading before the crisis, and when the system reboots, there will be no need any more to keep the shares, as they will stop being a hedge for the lira’s depreciation.”

On the other hand, Solidere has used the windfall of the last three years to pay down its debt. The quarterly report for the quarter ending June 2021 showed the company to be debt free, compared to 2018 when it owed $483 million.

On what the shares could fetch post the financial sector restructuring Barbir concluded, “The end game depends on the context in which these shares are being offloaded post restructuring. The technical aspect and the market depth will be important at that stage” — referring to shareholders who would be looking to sell after the restructuring because the shares would have lost their initial raison d'être as a hedge.

On the other hand, if the situation drags on, as it often does in Lebanon, and the lira drops further — another high-probability event — then the hedge will continue to work.

Disclosure: The author of this article owns Solidere shares.

Even though the $121,900 is in...