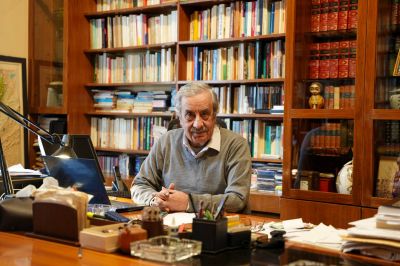

Charbel Nahas, in his house in Achrafieh, March 7, 2022. (Credit: Mohamad Yassine/OLJ)

There was no crowd that morning behind the doors of the al-Madina theater in Hamra. The sky was heavy, so were the hearts of the Lebanese.

Twenty-eight months after the beginning of the economic crisis and the outbreak of the popular uprising, 19 months after the Beirut port explosion, and 13 months after the assassination of Lokman Slim, many have given up on political work, either out of despair, resentment or survival instinct.

But in this apocalyptic atmosphere, the supporters of the Citizens in a State Party (MMFD) were still there. They still believe in it, almost religiously, as one clings to an idea that could solve everything.

Gathered for the launch of the party's campaign, less than three months from the May legislative elections, they looked busy, speaking in hushed voices, pacing up and down as if it were a matter of life or death.

Forty-five minutes later, Charbel Nahas, the party leader, climbed up on the wooden platform, receiving a standing ovation.

There was something messianic about the entrance, his look from the 70s and a Tom Selleck-like mustache.

Everyone in the room knows the experience of “Mr. Charbel Nahas,” former Telecommunications Minister (November 2009-June 2011) and then Labor Minister (June 2011-February 2012).

They have not forgotten that he was one of the first to warn about the coming economic crisis, when nobody believed it.

The gray-haired man fascinates people beyond the ranks of his party. His former students describe him as someone open to debate, a “walking encyclopedia” who “questions everything.”

“With him, any conversation is about political thinking and principles: it is never about other considerations as we can see elsewhere,” said a political analyst close to March 14 circles.

Out of fear or respect, few are those who venture to criticize him in public.

The sixty-year-old is known to be strict. He expects from others the same that he demands from himself.

“Don’t waste his time,” said one of his former students at the American University of Beirut.

Nahas does not deviate from his principles, always finds a way to guide the conversation back to an area he controls and shows a certain contempt for all forms of mediocrity.

But even in right-wing circles, where he is frequently confined to the cliche of the “old-guard communist,” he is recognized for being unusually smart.

‘Shock therapy’

Engineer, anthropologist, and economist by training, the former École Polytechnique graduate speaks in a haughty tone. He turned his intellectual background into an entire system of thought.

His book “An Economy and a State for Lebanon” (Riad al-Rayyes Books, 2020) is a collective reference.

It allowed him to export his reading grid beyond his close circles and to provide the basis for a common project.

MMFD is structured around the figure of the leader, but also around its internal bodies. They call this the “professionalization” of the party: Nahas and his followers are very proud of it.

“It is this clarity, especially the fact that he said what he would do from the first day in power, that made me join the party,” an MMFD member said.

Nahas is progressively rallying extremely heterogeneous profiles, beyond the traditional confessional or political schisms, from the ex-banker in finance to the Shiite youth from pro-Hezbollah backgrounds, who find in the personality cult and the party’s internal discipline a familiar vibe.

Some of the newcomers were drawn to the party, convinced by Nahas’ social approach, his commitment to a welfare state, universal health coverage, free education and the establishment of an egalitarian housing policy.

Others are there for the party leader's expert discourse on the transformative potential of the crisis as an “obligatory transition” toward a rebalancing of the economy through the development of national production.

There are also those who are attracted by his frontal approach, notably the “shock therapy” that he advocates in terms of secularism.

Sitting behind his desk in Achrafieh, where the scent of a bygone era hovers, that of printed atlases, bound books and antique knick-knacks, he is not reluctant to admit it.

“Secularism must be proclaimed immediately. It is not a question of getting there: to get there is already to give it up!” Nahas said confidently — another trademark of the 60-year-old, he cuts to the chase.

When the rest of the opposition groups refused to endorse the label of “party,” deemed too associated with the existing sectarian system and its parties, he was one of the first to dare engage into political confrontation at the national level.

When he resigned from his ministerial post in February 2012, he broke away from the Free Patriotic Movement with which he was allied in Najib Mikati’s government, then switched to the “anti-establishment” side, before creating MMFD in 2016.

At the time, the Beirut Madinati group, born the same year, favored a local strategy focused on urban issues.

He made the opposite bet by transforming each electoral appointment into a challenge against the system in place.

The former minister has gone from being a “personality,” best known to the general public for his stunning appearance before the cameras during the Chinese telephone network scandal in 2011, to a “party leader.”

Isolation

Despite the party’s increasing number of supporters, up to a few thousands today according to MMFD, Nahas' political journey sometimes resembles a balloon struggling to take off.

In the May 2016 municipal elections, the party fielded several candidates across the country. In Beirut, Nahas was leading his own list.

The fragmentation of the opposition groups (Beirut Madinati secured 35.5 percent of the votes and MMFD 8 percent) torpedoed the slim hopes of victory against a list sponsored by the traditional ruling class, which managed to garner 52 percent of the total votes, winning all the seats.

In the May 2018 legislative elections, MMDF joined forces with the Kulluna Watani group.

In 2022, the party appears to be deepening its electoral strategy, that of a nationwide election operation, presenting 55 candidates in each of the 15 constituencies.

The polls are seen as a referendum, “an opportunity to demonstrate our legitimacy,” in a bid to push the authorities to “transfer power for a limited period of time, on the basis of a program defined in great detail,” Nahas explained.

But by competing on separate lists — with the exception of South III, where he joined the unified opposition lists — he is flying solo.

“It is not a question of getting an MP here and another there: it is absolutely out of the question to make local arrangements that would be in direct conflict with the general orientation,” Nahas said sharply.

This uncompromising strategy has earned him criticism from some independents who see it as a selfish move that could kill the opposition by splitting it.

It appears that he has been increasingly isolated among the emerging opposition groups.

Perceived as a stiff-upper-lip, elitist or representative of an archaic left, critics say he does not stand out as a figure capable of transcending the new political schisms or of taking the leadership of an alternative project.

He is one of the representatives of the opposition groups to decline the invitation of French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, visiting Beirut in May 2021.

Some of the left-wing revolutionaries, whom he could have convinced with his socio-economic analysis, do not forgive him for his complacency on the issue of Hezbollah's weapons.

In the South as well, where anti-Zionist rhetoric and socialism are part of the local political soil, he could have imposed himself as an alternative to Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, and mobilized this electoral pool as a springboard to establish his legitimacy at the national level.

But here again, Nahas’ positions are not in line with the concerns of many, including those of the anti-Hezbollah front, dedicated to fighting the Party of God’s hegemony, as well as the religious portion of the population that is not too comfortable with the idea of secularism advocated by MMFD.

In Nabatieh, for example, “MMFD is only hindering the process, they are not welcome in the ranks of the Shiite opposition,” said Karim Safieddine, an official in the Mada group.

“At the same time, they operate outside the framework of the Party of God, and therefore they will neither have the protest movements’ votes nor pro-Hezbollah votes,” he added.

‘Hyde Park effect’

Yet here it is. The MMFD founder built the heart of his political doctrine on the heritage of an anti-Zionist Arab left, anti-Haririst approach, and a form of French-style Jacobinism.

The Nahas matrix is anchored in the past. It continues to give pride of place to the great upheavals that have shaped the region over the past century — the “Zionist project,” the world wars, the invasion of Iraq in 2003, among other major events.

In Lebanon, the Civil War was a rupture.

For the country as well as for Nahas, who lived in Paris until the early 1980s, the war years represent a traumatic event that disrupted the Lebanese social fabric and paved the way to the destruction of the state.

His reading of the bankruptcy of the system, in place since the mid-1980s, also leads him to denounce the public over-indebtedness, the structural deficit, the “economy of plunder” and the political-financial oligarchy embodied, according to him, by the Hariri family.

The establishment of a strong secular state transcending particular interests is thus thought to be an antidote to the slow decomposition of the country.

This discourse, especially its economic component, had its moment of glory with the 2019 popular uprising.

Worried by certain indicators (exponential rise of the debt and inflation, among other things), Nahas warned in the early 2000s of the risks of a monetary and financial crisis caused by “the primary characteristic of the Lebanese economy which is in a persistent and enormous deficit of the current account balance,” he wrote in Studies of Economic Risks in Lebanon, in February 2002.

The Oct. 17, 2019, uprising and its aftermath validated these theses, which a portion of the Lebanese population had previously considered far-fetched — something that lent more credibility to the party.

“The crisis became real in the eyes of all, and the discourse we were carrying became audible, which pushed several people to join MMFD,” explained Nour Kilzi, a party member since the 2016 municipal elections.

It is the “Hyde Park effect,” said Karim Mufti, a professor and researcher in political science, which allowed the party to make its voice heard in the public squares, such as during the debates under the tents that took place in downtown Beirut during the demonstrations.

But then the sequence of events played against him as “he lost monopoly over the total opposition to the system, in favor of advancing a political project of rupture with the regime,” said the political analyst close to March 14 circles.

“He will now be diluted in a myriad of movements who share the same stance,” he added.

For a portion of civil society, the MMDF’s political culture and centralization belong to yesterday’s world.

The personalization of the party by Nahas, who was re-elected a few months ago as secretary general for a new three-year term, remains too much associated in the collective imagination with the traditional figure of the zaim (political leader).

MMFD, for its part, rejects any accusations of authoritarianism. Bassem Snaije, a member since 2020, said that “Charbel Nahas is not always right.”

“But, once an approach has been chosen, everyone falls in line behind it: it's not a tea house,” he added.

But the bulk of progressive forces, who are more inclined towards horizontalgrassroots and decentralized forms of organization, take a different path.

Ambivalence

Between 2019 and 2021, the issue of Hezbollah has increasingly become pressing in the public debate.

The 2019 uprising tore down the wall of fear and freed up speech, with more and more public figures from the Shiite community s publicly opposing the Party of God.

The party is alleged by many to be behind the 2020 Beirut explosion and the assassination of Lokman Slim, a staunch opponent of Hezbollah — something that accentuated this polarization.

“Many felt under pressure to show that they had, at least, a clear position on the subject,” said Safieddine.

For its part, MMFD continues to cling to its traditional line, despite a few inflections in its discourse, particularly when it comes to denouncing Hezbollah’s responsibility in the corruption of the political and financial system.

The subject of arms, on the other hand, is considered only from the angle of legitimate defense against the Zionist threat.

“The state has real reasons to deal with the Zionist project as an aggressor and to bear the costs in terms of mobilization, armament,” insists Nahas, who denies any ambiguity on the issue.

His position supports the integration of Hezbollah’s military resources into the state institutions, once they have been reformed. In the meantime, there are other pressing urgent matters.

For some of the protest movements and a portion of the public opinion that perceives the Party of God as a danger as pressing as the Zionist threat, if not more so, this discourse is not quite on point.

“The true weight of Hezbollah on the Lebanese political scene is not recognized,” Safieddine lamented.

The same ambivalence applies when it comes to Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

On the regional scene, pragmatism and reasons of state prevail over any other consideration: for Nahas, Damascus’ dictatorship is not problematic in itself, or in essence, but insofar as its toll on Syria impacted the stability of Lebanon.

Here again, this language is hardly acceptable to the protest movements close to the March 14 camp, which has fresh memories of the Syrian presence in Lebanon, as it is to a portion of the Lebanese youth sensitive to transnational liberation movements and popular solidarity.

For the latter, Assad remains above all the “butcher of Damascus” who deployed his war machine against his people during the 2011 revolution.

Riding the wave of the Oct. 17 uprising, while refusing to acknowledge the revolution next door is a contradiction that is difficult to overcome for this youth with whom he is out of step.

Nahas is seen as a “political dinosaur” in an emerging opposition that lacks his background standing, and experience of power.

“In the face of young people, he inevitably appears harder, more patriarchal, more elitist too,” Mufti said.

There is therefore “a natural apprehension: the remaining space to exist is narrow when he is present,” he added.

“A hardliner,” “unmanageable,” “stubborn,” “too theoretical”: this is how his detractors describe him.

His interlocutors regret his lack of flexibility, sometimes at the expense of the realities on the ground, and emphasize his difficult character that burdens negotiations in the ranks of the opposition.

“He expresses himself like a school teacher, he is convinced that he has the right vision of things, whereas his approach is anything but pragmatic, there is never anything concrete,” said an official in a party who is in contact with MMFD.

While he formalized his candidacy for the legislative elections in the constituency of Beirut I, against two other independent lists, Nahas could pay the price of this solitude in the ballot box.

The article originally appeared in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghobssoub.