A man counts banknotes at a shop in Beirut. (Credit: Reuters)

BEIRUT — After dropping to its lowest value ever earlier this month — trading at LL33,700 to the dollar on the parallel market — the lira rallied significantly this week and is now hovering at around LL23,000.

The strengthening of the lira comes alongside a series of measures by the central bank intended to prop up its Sayrafa exchange platform and edge out the parallel market exchangers. For the time being, the attempt seems to be working, but experts and banking sector insiders question whether it is sustainable.

Since 2019, the Lebanese population has suffered through a broken banking sector, runaway inflation, shortages of basic goods and a national currency caught in an endless death spiral. The two successive governments since then, like many of their predecessors, offloaded the job of extinguishing fires to the central bank.

Against that backdrop, Circular 161 is Banque du Liban's latest attempt, in a series of monetary measures, to normalize the country’s economic reality.

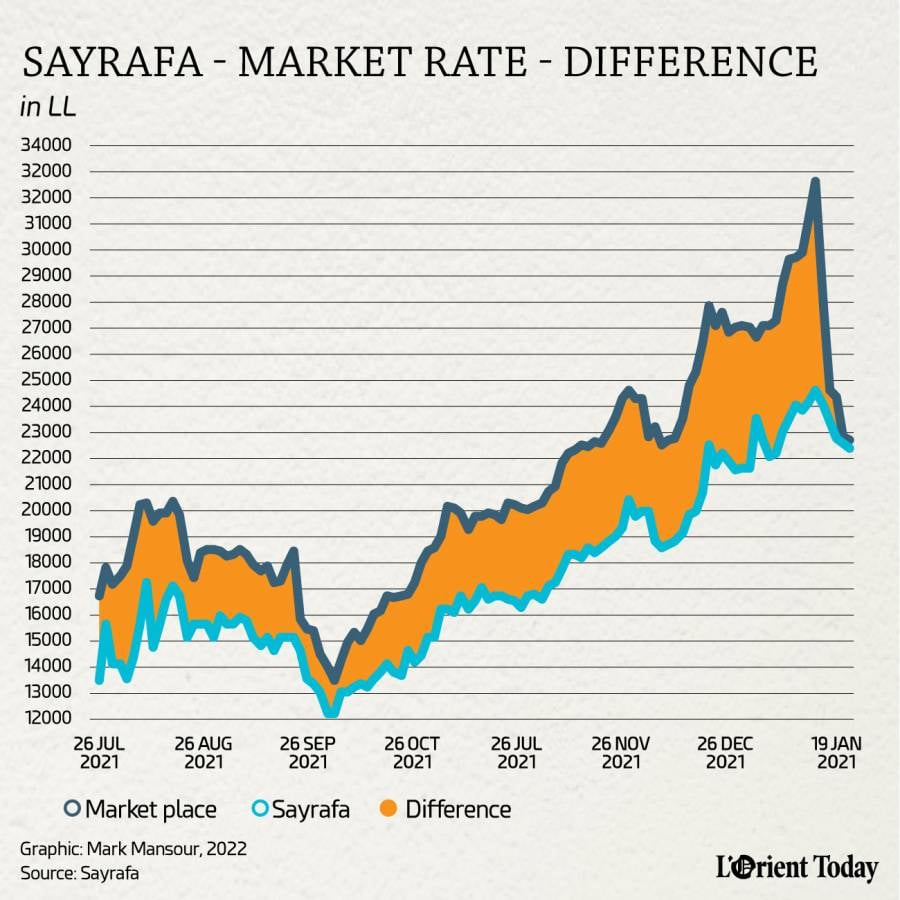

The circular in its first iteration, released on Dec. 16, promised to make available through banks US dollar banknotes at the Sayrafa rate, which was then set at LL22,300 while the parallel market rate was at around LL27,500. While the new mechanism allowed people to make an instant profit by buying from the banks at the Sayrafa rate and then selling to money exchangers at the market rate, the currency market remained unfazed and the lira continued its downward spiral.

Two weeks after the circular’s release, the lira was already at an all-time low of LL33,700 to the dollar, with forecasters predicting its continued demise. Fearful of further public outcry, with both parliamentary elections and International Monetary Fund negotiations on the horizon, Prime Minister Najib Mikati gathered Finance Minister Youssef Khalil and Banque du Liban Governor Riad Salameh and instructed them to do whatever it took to stop the lira from losing further ground.

Thus was hatched the second iteration of Circular 161, released on the back of the high-level meeting of Jan. 11, as the lira was falling through the floor.

The new version contained a major upgrade. The central bank promised, this time around, to remove all quotas on the monthly lira liquidity it provided to banks and to make available dollar banknotes in an unlimited quantity. The currency market heeded the call, and the lira rose around 47 percent in the span of a little less than two weeks.

One banker, who — like other banking sector insiders — spoke to L’Orient Today on condition of anonymity, compared Salameh’s promise to flood the market with an unlimited quantity of US dollar banknotes to the European Central Bank’s strategy in 2012, when its President Mario Draghi promised “to do whatever it takes” to defend the euro. The two situations differ in many of their details, but they share the same strategy to influence public sentiment and break the cycle of negative momentum.

Nonetheless, the size of the recent correction is not unprecedented. Between July 16, the day after Saad Hariri stepped aside as premier-designate, until the designation of Najib Mikati as prime minister on July 26, the lira rose from LL23,300 to LL16,600 to the dollar, or about 40 percent, and then from Sept. 9 to Sept. 16, it rose again, from LL19,550 to LL13,650 or about 43 percent, when Mikati formed the new government.

In any case, the new measure seems to have momentarily succeeded in breaking the vicious cycle of lira depreciation and provided much-needed stability, although the exchange rate is still more than 90 percent lower than the peg of LL1,507.5 to the US dollar, and about 40 percent lower than the high reached in mid-September.

The effectiveness of Circular 161 was not only limited to reining in the sharp selloff in the lira, but it also validated the concept behind the obscure BDL platform, previously known only to bankers and money exchangers. The Sayrafa platform, named for the Arabic word for banking or money exchange, was initially set up to fight off illegal money exchangers, and to render more transparent the day-to-day dealings in the US dollar. It required registered money exchangers to report back to the central bank all the foreign currency trades between them and their clients.

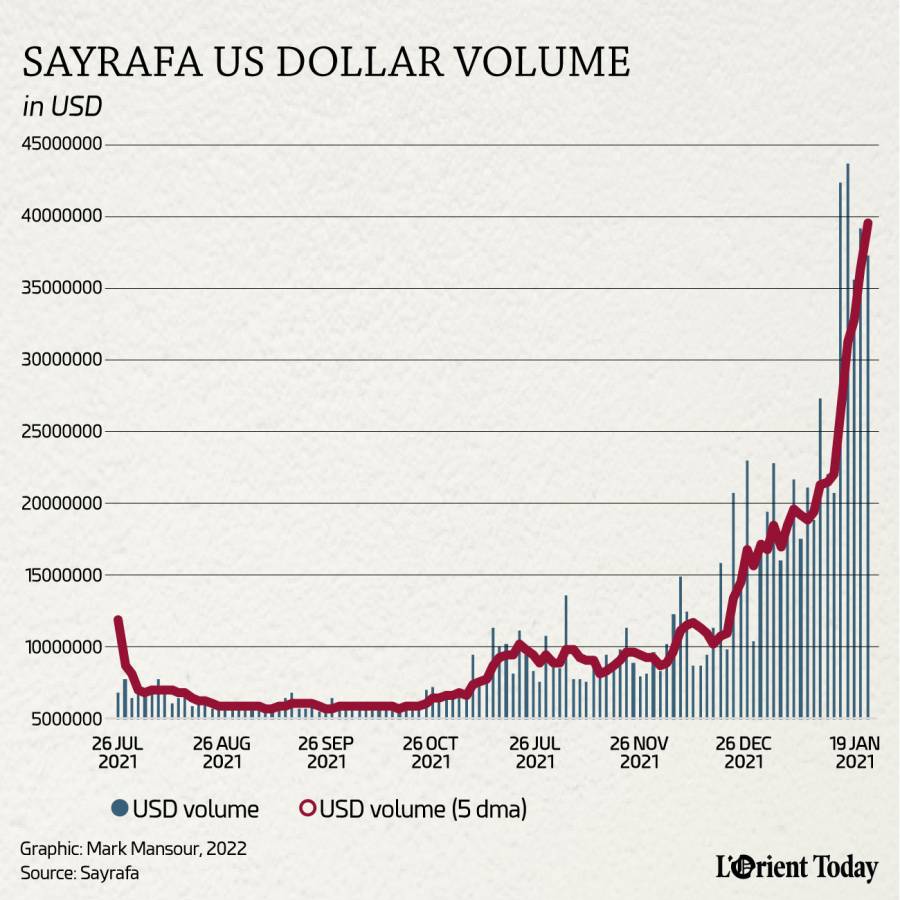

From July 26, the date when the central bank began reporting daily the Sayrafa rate, until Oct. 12, the date when the money transfer company OMT was added to the platform, Sayrafa recorded lackluster amounts of transactions. The average daily dollar amount traded during this period was less than $1.5 million.

In a bid to increase the volume traded through the platform and make the pricing truly reflective of the demand and supply dynamics, the central bank added the banks and the money transfer companies to the fold. Between Oct. 12 and Dec. 16 — the date Circular 161 was released — the average daily dollar amount reported on the platform rose to $5.4 million, a more than a threefold increase.

Between Dec. 16 and Jan. 11, the date when dollars were promised to the banks in unlimited amounts, the average daily dollar amount recorded tripled again, as measured from the previous period, to $16 million. Since Jan. 11, the platform has been recording amounts of more than $35 million. While the sample is still small to draw any long-lasting conclusions, BDL’s strategy appears to be working, at least for the time being.

Salameh has always asserted that only the transactions recorded on the Sayrafa platform are an accurate reflection of the lira’s value. He has repeatedly called for the shutdown of other illegal and suspicious applications, claiming that these platforms only enable price manipulation, sow confusion and generate profits to few traders.

On Jan. 4, the central bank issued warnings to 188 money changers for their failure to register the sale and purchase of dollars on the Sayrafa platform. In the event that they fail to comply within 40 days, they risk having their licenses revoked. More recently, Judge Ahmad Mezher issued a preliminary ruling appointing expert David Salloum to trace the illegal platforms to shut them down.

According to a senior bank official, this is a classic “winner takes all strategy,” but with a twist: the central bank has the full weight of the government behind it. This means that the Sayrafa platform “will rule them all” and will end up capturing most of the market.

He added, “All the governor’s actions to this day point towards this eventuality.”

Furthermore, by unifying the market rate and the Sayrafa rate, Salameh would have succeeded in shutting down the claims that Sayrafa is consistently overvaluing the lira, and that it is not a true reflection of the US dollar to the lira market.

Data compiled by L’Orient Today, show the Sayrafa lira rate to have been, on average, more than 15 percent stronger than the parallel market rate, but since Jan. 11, the difference has compressed down to about 2 percent.

If the strategy succeeds in the long run, Salameh would have inched one step closer to fulfilling one of the IMF’s conditions for financial assistance, which is the unification of Lebanon’s multiple exchange rates.

Sayrafa’s domination of the currency market will also provide the central bank with the opportunity to supplant the money exchangers who fall outside of BDL’s direct control and to replace them with the banks, which are under its direct supervision. As a result, the banks have become the de facto new money exchangers.

Money exchangers contacted by L’Orient Today said that clients were no longer buying dollars from them, and few are still selling, while an increasing number are taking their business to the banks.

Clients receiving dollars from their banks at the Sayrafa rate and in need of lira do not have any incentive anymore to sell their dollars to a money exchanger at the same Sayrafa rate. It is more convenient for them to sell their dollars, on the spot, back to the bank. In turn, the bank will record both transactions on the platform, and this is how Sayrafa will gradually capture most of the flow in the market.

So, with the increasing dollar amounts being recorded on Sayrafa, the recent convergence of the parallel market rate and the Sayrafa rate, and the crackdown on other platforms and illegal money exchangers, Salameh’s strategy appears to be succeeding at gradually taking over the exchange market and consolidating it under the central bank’s control.

NGOs are among those who will benefit from this turn of events. Previous reports have indicated that NGOs that receive funding in dollars from abroad were shortchanged by banks on their dollar-to-lira conversions; this fact was assumed to be an important reason behind the difference in rates between Sayrafa and the parallel market. But now, NGOs will be able to transact at the Sayrafa rate, which has become the same as the market rate.

If Sayrafa captures the currency trading market, it will also have significant impacts on the conduct of official government business. If the country moves officially from a pegged currency system to a floating one, the government will need a reference rate for its budget, for tax collections, for foreign currency contracts and for all other related businesses.

Will the strategy work in the long run?

Some experts who spoke to L’Orient Today believe the central bank and government ministries are wasting their efforts tracking down exchange rate applications and illegal money exchangers. They argue that the root cause for the lira’s depreciation is not the proliferation of online platforms nor the handful of individuals dealing in the US dollar, but rather the country’s deteriorating economic fundamentals.

They argue that the loss of confidence in the lira, on top of a long-standing breakdown in governance, is the logical result, first, of a decadeslong monetary policy that led to accumulation of losses on the central bank’s balance sheet, and second, to the mismanagement of foreign currency reserves during the most recent crisis.

The government’s subsidy policy during the crisis is a case in point. According to the former Finance Minister Ghazi Wazni, subsidized imports cost $6 billion annually, draining the foreign currency reserves, but only a small percentage of the goods went to those in need. A report by UNICEF and the International Labour Organization noted that just 20 percent of the subsidies went to the poor, while the other 80 percent either benefited the wealthy or lined traders and cross-border traffickers’ pockets.

Another senior banker who spoke to L’Orient Today questioned “why this money was not used to pay back deposits and shield people from the lira’s depreciation” or “used for the upgrade of the energy infrastructure and other investments in essential social projects.”

Some expressed concerns that the recent actions by the central bank were stalling tactics, similar to the ones used in the years before the financial crisis to attract fresh dollar deposits, in what has come to be known as financial engineering. These tactics can buy time, but they cannot offer long lasting solutions.

There was a consensus between the bankers interviewed that the risk of Salameh’s strategy ending in failure is high, particularly in the absence of a cohesive economic plan, combining both fiscal and monetary tools.

The absence of a sound fiscal strategy and the utter reliance on an unimpeded central bank governor have already led the country to its current situation, one banker said: “More of the same is not the answer.”

There is also the fact that foreign currency reserves are finite, and they have dwindled at an alarming rate. Draghi had the euro’s printing press and Europe’s might to back him up, Salameh has only whatever is left of foreign currencies in Lebanon, currently estimated at $12-14 billion.

If the central bank continues to pump dollars into the system at the current rate of $30-40 million a day, it will add up to $1 billion in one month, just shy of 10 percent of the remaining reserves. Pegging the lira to LL24,000, like pegging it to LL1,507.5, would require ongoing interventions, and the strategy could backfire if the market catches a whiff of the central bank reaching the end of its rope and that no further market interventions are possible. This could happen because the interventions’ half-life has become infinitesimally small on the back of diminished reserves of foreign currency or if the government fails to reach a deal with the IMF.

Either one of these scenarios could send the country into a tailspin in which the lira will be impossible to defend, and the country will fall into hyperinflation.

When asked by L’Orient Today how long the central bank is prepared to continue its intervention in the market, a BDL spokesman said there is “no deadline” and pointed to Salameh’s recent comments to that effect.

Meanwhile, although for now Salameh appears to have Mikati’s support, he still faces an uphill battle, amid several international investigations into his practices and some former political backers calling for his resignation.

Even the banking community has become disenchanted with the governor’s performance. A senior banker told L’Orient Today on condition of anonymity, “For someone in Salameh’s position, adhering to best practice and using some common-sense would have dictated that he immediately resign his position.”

The banker added, “Lebanon needs cool and focused heads to help it navigate the crisis and not officials embroiled in [allegations of] money laundering, embezzlement, and fraud.”