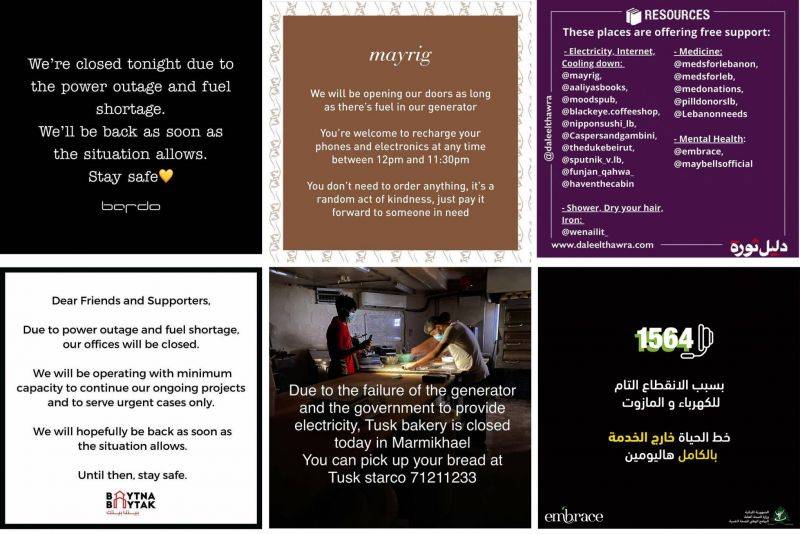

A collage of announcements from businesses closing, reducing hours or inviting people to use their electricity. (Credit: DR)

Dozens of messages were sent. Some announced the shutdown of air conditioners, reduction of working hours or even temporary closure. Other messages communicated neighborhood generators’ power supply schedules, inviting the public to drop by local shops if they need to recharge their phones or computers for free.

Banks, shops, restaurants, malls, bakeries, educational centers, bars.

Merchants and entrepreneurs, which have already been in a critical situation for months amid an acute economic crisis, are out of breath after Banque du Liban Gov. Riad Salameh announced an immediate halt to subsidies on Aug. 11. What the decision’s implementation will look like is unclear as politicians have launched into a fatal political game that led the country into another hellish vortex that climaxed with the fuel tank explosion in Akkar this past weekend. The explosion killed at least 35 people and wounded scores more.

“Due to a power outage and fuel shortages,” began messages sent by shops and businesses, particularly on social media. Most of them ended with an announcement that they will close their doors, which took students, employees and other customers — who had to resort to these establishments due to power cuts at home — by surprise.

The blackouts began weeks ago, as many private generator owners ran out of diesel, forcing them to switch their machines off and causing many Lebanese to slip into total darkness.

Still, private generators are the only shield against a 24/7 blackout as the state power utility, Électricité du Liban, is unable to provide services.

EDL’s current capacity is 750 megawatts, caretaker Energy Minister Raymond Ghajjar said recently, while electricity demand this summer has exceeded 3,000 MW, leading EDL services to be absent most of the time. On Sunday evening, EDL announced a total blackout after it lost control of some transformers.

Meanwhile, recently negotiated fuel imports from Iraq continue to be hamstrung by administrative paperwork that will persist for “a month,” according to the minister. This fuel oil will also not be immediately usable as it does not meet the specifications of Lebanon’s power plants.

As a result, the country’s lights go out, the streets are deserted and businesses struggle to survive, projecting the image of an entire nation gasping for air.

The battle is on

Illuminated by candlelight, the hotel, restaurant and bar Lost, located in Beirut’s Gemmayzeh area, chose to remain open, serving a few clients. “The situation can be characterized as tragic,” says its owner, Michel Abchee. “We have reduced our menu, offering only dishes whose ingredients can withstand a power outage of up to two hours or require less cooling,” he adds.

The cold chain is the obsession of Abchee, whose group also owns the City Mall shopping center, which closed on Saturday.

“It is imperative to maintain the cold chain at all costs. We have saved enough diesel for the refrigerators of the restaurants in the shopping center, in addition to those at the Carrefour supermarket and the Red Cross vaccination center,” he says. While refrigerators keep humming, all of the restaurants have closed, leaving Carrefour and the inoculation center the only operating enterprises.

To keep their doors open and maintain the cold chain, entrepreneurs and merchants are now forced to buy diesel on the black market at an exorbitant cost.

“I consume 360 liters of fuel per day, which I am now forced to search for on the black market, where 1 ton is sold for a sum ranging from LL20 million to LL25 million,” says Aline Kamakian, the owner of Mayrig, an Armenian restaurant in Gemmayzeh.

It is an astounding sum at a time when 1 ton should cost LL1.17 million, based on the official prices, last set on Aug. 11 by the Energy Ministry. Added to the cost is the energy and time consumed in the search for the diesel.

Heavily affected by the 2020 Beirut port explosion, the restaurant and its employees have recovered and are working relentlessly to face this new crisis.

“We are at the mercy of our leaders, who want to bring us to our knees in submission,” she says. “But I refuse it. Together, we can start a movement.”

Faced with the crisis, and with the recurrent assaults on the dignity of the Lebanese, Kamakian on Saturday provided the opportunity for anyone to use the electricity supplied by the generator at her restaurant without having to purchase anything.

Her message circulated on social media and had a bandwagon effect, prompting other merchants and restaurateurs to follow suit.

Graphic designers working internationally even called to ask whether they could come with their desktops, she said, and explained that she had to “add extension cords.”

At the same time, the bar adjacent to her restaurant decided to close, because it ran out of diesel. Kamakian did not hesitate to offer them to use Mayrig’s generator. “If we have to close, we will close together,” she told them.

A matter of survival

Businesses across the country are now waging a collective fight for survival. In the southern city of Saida, Ringlet, a personalized learning center, closed indefinitely last Friday.

“We have been battling for a month to find solutions to power rationing,” explains Rawan Affara, who owns and manages the center. “Our building is also home to medical centers, so we were kind of reassured. But the situation worsened, and power cuts became more frequent and for longer hours, to the point that it was impossible to connect a fan.”

In late July, she received an electricity bill for LL1 million “for a power supply that we haven’t seen!” Under such circumstances, work has become a full-fledged ordeal for the teachers and students at the center. “Parents phoned me to cancel the sessions because their children could no longer stand the heat and, above all, some houses no longer had access to water, and the families could not take care of their children’s hygiene,” she says.

The center, which was founded in 2019, thrived in the disadvantaged city, although Lebanon’s crises had already kick-started back then. It is a victory for the young woman, who launched the center’s online educational platform just before the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020.

Digital technologies have become key for online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic, but they are now at stake because of power cuts and ensuing internet outages.

“We are recharging internet data on our teachers’ mobile phones twice a week to enable them to continue to give online classes and use the platform without electricity. But what about the students?” she asked. “Every time we find a solution, it becomes meaningless the next day as a new problem sweeps it away,” she says.

As Lebanon’s crises accumulate, “we will continue to seek solutions, because everything lies on our shoulders in a country where the state is absent,” she says.

Café Blend, a stone’s throw from the city center, is more fortunate. “For now, the generator owner has not reduced supply hours. I think he is the only one in Saida who has not so far,” Feras Naffaa, the owner, says.

It did not happen by chance. “I made him an advance payment of LL15 million for the month of August, but I don’t know how much he will charge me for next month.”

While the situation condemns all Lebanese entrepreneurs to the unknown, the severity of the cuts depends on the region. Naffaa also owns three branches of Coffee Feras Naffaa, all located in the south. While the branches in Nabatieh and Sur open only two to three hours a day, depending on power supply, the Saida branch has its own private generator that Naffaa pays for. Presently, he is paying LL300,000 to buy 20 liters of diesel on the black market, which is nearly five times the official price.

A morbid landscape

Not only are power outages happening randomly, depending on factors both controllable and uncontrollable, prices are also fluctuating and subject to negotiation, whether for diesel or other fuel prices, and whether on the black market or at gas stations.

In the Bekaa Valley, every gas station acts according to its own liking.

While the vast majority of stations are closed, having run out of stock or due to fears of clashes with customers, others are selling fuel at a rate higher than that set by the ministry but lower than the black market price, where last Friday 20 liters of gasoline were being sold for LL340,000.

The service provider in the Bekaa city of Zahle, Électricité de Zahlé, is also imposing shortages as it struggles to bridge EDL’s deficits. Several restaurants temporarily closed their doors and reopened after increasing their prices.

A butcher in the city recounts that he is opening the meat stall only when there is power, and that he communicates the supply schedule to his customers every day. A resident of Hermel, also in the Bekaa, explains that all shops switched off their refrigerators, which are now used only as a “decoration.”

“People’s lives have totally changed,” she says.

In Lebanon’s poorest city, Tripoli, blackouts are not new. “The circumstances in Tripoli are even more complicated, given the years of neglect the city has suffered by investors despite its capabilities,” says Toufic Dabboussi, who chairs the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture in Tripoli and North Lebanon.

Prior to this latest turn for the worse, “many businesses in the city and surrounding areas had either gone bankrupt or temporarily closed, waiting to see how the situation would unfold,” he adds.

“The latest developments related to the fuel prices and availability have forced many bakeries, snack bars and restaurants to close or reduce business activity to a minimum, opening only when there is power supply. Others have limited their business to orders made by their regular customers — including hospitals — which they have to serve,” he adds.

In addition to shops, the state offices have been also affected by the diesel shortage and the lack of — if not total absence of — electricity, “thus impeding all procedures that need to go through them,” Dabbousi says. If BDL and the Energy Ministry agreed on a price that importers will capitulate to and sell their stock at, gas stations would resume sales. This solution, however, is only temporary.

A total or partial end to fuel subsidies would lead to price hikes of more than 300 percent, taking into account Wednesday’s average exchange rate of LL16,500 to the US dollar on the central bank’s currency exchange platform, Sayrafa, which is expected to be used as the basis for sales of dollars to fuel importers.

“In any case, given the steep depreciation of the Lebanese currency and the decline in business due to the crisis, a lot of businesses would rather shut down than open and lose money,” Dabboussi says. That is, if they were still able to open.

From now on, merchants and entrepreneurs will have no choice other than to deal with this daunting situation day by day, desperately waiting for some ray of hope to pierce the darkness.

This article was originally published in French in L’Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.