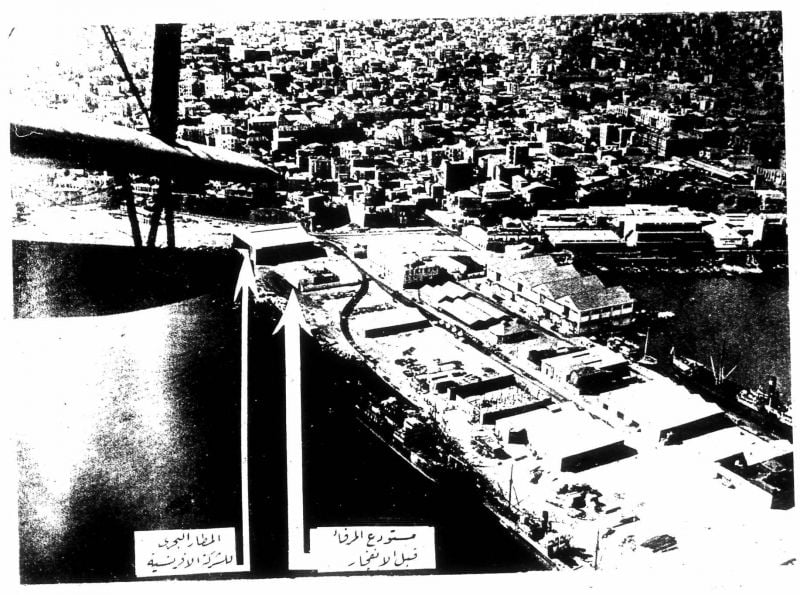

Aerial photo of Warehouse S (right) at the Beirut port before the 1934 blast, next to the seaplane hangar (left). (Source: Al-Maarad, 1934. American University of Beirut Libraries)

A port warehouse filled with improperly stored explosive materials. Rescuers searching for victims trapped underneath wreckage. Grief inflicted on innocent families. News of a catastrophe making headlines around the world. A city and a nation left in shock, looking for answers, and an investigation going nowhere.

The situation sounds eerily similar to the events that have unfolded since Aug. 4, 2020, but this tragic event took place almost 88 years ago.

I initially learned of the 1934 Beirut port explosion while researching post-disaster recovery in the wake of last year’s blast. The similarities between the two were uncanny. Oddly enough, although it was widely covered in the news at the time, I found no mention of the 1934 blast in books about the port. Instead, I pieced through the story using archival newspapers, maps and aerial footage.

On Dec. 1, 1934, at 8 a.m., as reported by local media at the time, 30 workers started their shift inside Warehouse S in the Port of Beirut. At 8:01 a.m., a powerful explosion ripped through the facility, causing a massive fire. It took one minute for the warehouse to collapse; its metal roof caved in, trapping all 30 people underneath it. Had the roof been securely fastened, its sprinkler system could have extinguished the blaze. Instead, smoke and flame billowed through the whole area. The Palestine Post reported that families of the victims rushed to the scene to see if their loved ones were safe but were unable to reach the site, which was cordoned off as firefighters worked for hours to extinguish the blaze; while reporters covering the incident were harassed by the police.

Rescue workers were faced with an impossible situation as they could not safely dig out those buried beneath the wreckage without harming them. Finally, they managed to cut a hole through the metal roof to gain access. Rescuers told the newspaper An-Nahar that the corpses they recovered had been burnt alive: skin melted onto bare bones. Others had been decapitated or had limbs and skulls smashed. One victim had food in his mouth because he was having breakfast at the time of the explosion. The youngest victim was an 8-year-old boy playing near the port when disaster struck. In total, the blast killed 20 people and injured 14 others.

Medics transported the wounded to Hotel Dieu de France hospital; there, families waited for news of their loved ones. Many of the bodies were identified through personal belongings; in one case, through a love letter found in a person’s pocket. One survivor told an An-Nahar reporter that he had heard a sound like thunder before he was set ablaze and jumped into the sea. The next day, funerals were held to mourn the dead as search parties continued to look for the missing, while military and police officials salvaged what they could from the ruins.

The port was evacuated immediately and closed for the day. The rest of the explosive material was removed to prevent another disaster, while traders tried to save as much merchandise as possible. Over 90 percent of the destroyed goods were uninsured. Moreover, 11 crates of film reels were damaged, leaving Beirut’s cinemas without new movies for a week.

A dispute arose over who was responsible for this travesty: the Compagnie du Port, which was the company that ran the port at the time, or the port authority. The public was outraged that more precautions had not been taken and questioned why hazardous material had not been handled better. Two days later, on Dec. 3, authorities launched an inquiry into the cause of the blast. Two investigators were appointed to lead it, Mr. Gary and Mr. George. At the time, An-Nahar predicted that this would lead nowhere, as two previous port explosions with one casualty each (in 1919 and 1928) had gone unexplained and without consequence. Indeed, the investigation into Dec. 1 was shrouded with secrecy, and ultimately, nothing came of it.

An independent investigation by An-Nahar found that Warehouse S was designated for explosive and combustible materials only and housed TNT, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, gunpowder and liquid silver. Access to it was supposed to be restricted to employees and only when necessary. However, space was becoming scarce at the port as new tariffs introduced months earlier had created a backlog of imported items. With nowhere to put the extra stock, customs officials began to use Warehouse S to store flammable goods, such as silk, cotton and wool as well as cheese, meat and fish.

As for the cause of the blast, news outlets and authorities posited multiple different theories.

Both An-Nahar and Al-Maarad speculated that while making room for more of these additional items, workers had moved hydrochloric acid tanks in an unsafe manner, causing them to blow up and ignite other chemicals and setting off a chain that culminated in the giant explosion. The improperly stored flammable material fueled the raging blaze for hours. An-Nahar also suggested that dynamite thrown into the sea to clear ship wreckage for construction on the new terminal might have ridden the current to Warehouse S and triggered the blast. Meanwhile, The Palestine Post cited experts who pinned the cause down to the mixture of nitric acid with improperly stored chemicals. For their part, port authorities blamed the catastrophe on the ignition of gunpowder being transported by a small ship, which then set off the rest of the material. Rumors also circulated that a cigarette butt had been thrown into the tanks.

In the end, the official or officials who made the tragic decision to allow an explosives depot to house flammable merchandise were not identified; no one was prosecuted or arrested for the warehouse’s structural deficiencies that caused the roof to collapse and the sprinklers to fail. The compensation promised to the victims’ families was not paid, despite a motion being passed in Parliament two days later. The government did not follow through with it, and no budget was allocated for the payments. Justice was not served. Moreover, the memory of the disaster was spatially erased: a row of new warehouses was built over the scene of the crime, the road network around it was reordered, and the border it shared with the sea was gone once land reclamation commenced on the new port terminal in the following months.

It became hard to locate the site of the disaster. You could no longer just point and say, “That’s where it happened.” This was how the past was silenced.

Aug. 4 should not have the same ending as Dec. 1: relegated to the dustbins of history. The way to prevent this is to hold those responsible accountable for their grave mistakes; we simply cannot allow this cycle of immunity to continue. Moreover, compensation to the victims and their families should account for the currency devaluation and should go beyond financial reparations to include psychological welfare and long-term care for all, including those left with lifelong disabilities.

Finally, decisions about what to do with the blast site should encompass the memory of the disaster and its victims. Recent proposals either erase the consequences of the tragedy completely, as in the case of the German companies’ vision, or impose memorials from above, as in the case of Nadim Karam’s statue. Any memorialization needs to be participatory to include those affected, so as to create a site of public memory that allows for reflection on what occurred and reminds those responsible of their shame.

Mohamad El Chamaa is a researcher at the Beirut Urban Lab (AUB) and a volunteer with Offre Joie. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in history and is finishing his Master's in urban planning and policy. His thesis focuses on long-term housing solutions in Karantina in the aftermath of the Aug. 4 port explosion.