Syrian children attend lessons organized by community activist Khaled al-Youssef in the Bekaa village of Dalhamieh. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

DALHAMIEH, Zahle — Amid the prolonged closure of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic, enrollment rates in Lebanon have fallen and dropouts have increased, while child labor is on the rise among Syrian refugee children.

Some 1.2 million children in Lebanon — Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian and others — have had their education disrupted due to COVID-19-related school closures that began in March 2020, according to UNICEF.

For Syrian children, who already faced many barriers in access to schooling before the pandemic, the combination of school closures and increasingly harsh economic conditions has had particularly stark consequences.

“The economic situation was very, very sluggish even before corona. … Many students left school even before corona, and after corona this increased,” Rabea Alkadri, a Syrian community activist in the Bekaa, told L’Orient Today. Dropouts increased due to school closures, she said, because “for the Syrian students in most of the schools, there was no continuation online.”

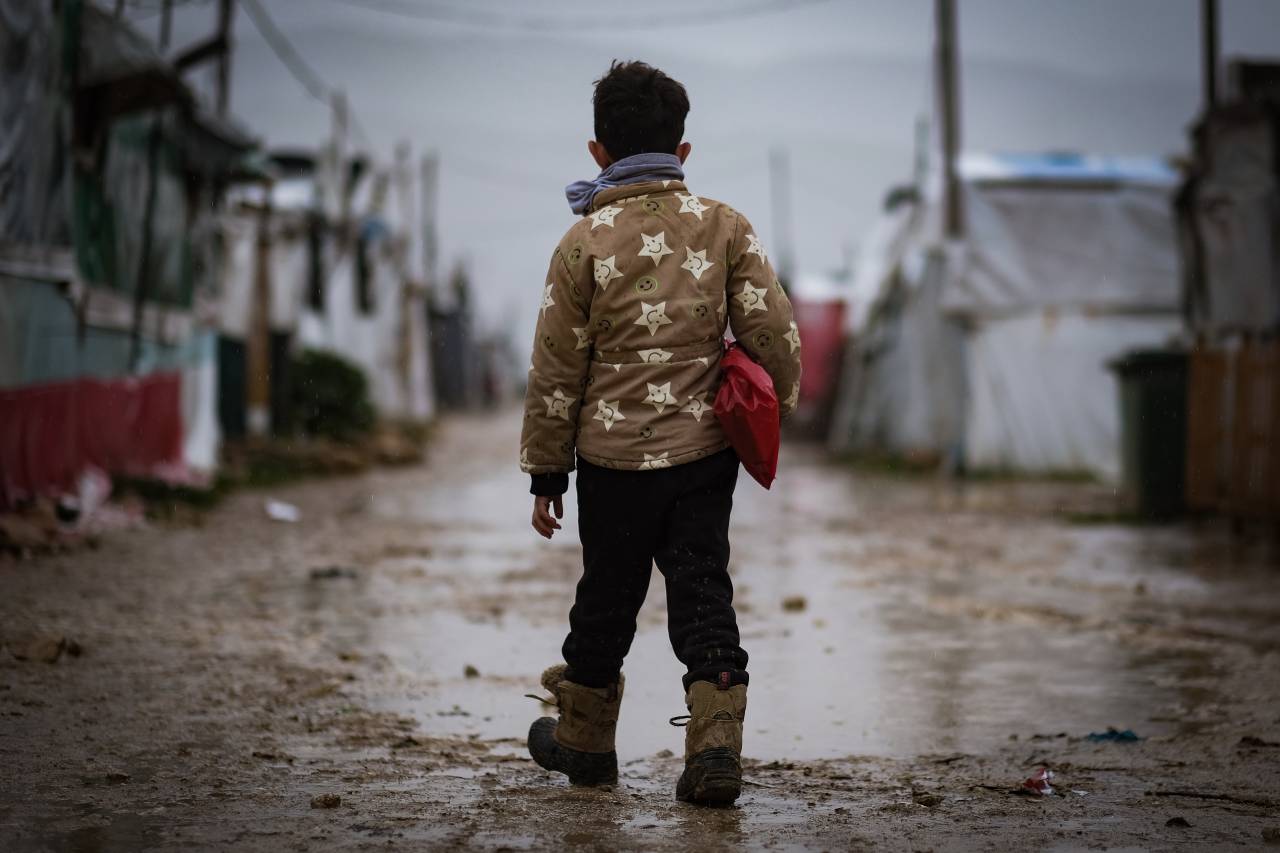

A boy walks through the refugee camp in Dalhamieh where an informal school teaches children. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A boy walks through the refugee camp in Dalhamieh where an informal school teaches children. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Ziad al-Kharsan, a Syrian refugee living in Choueifat, told L’Orient Today, “My son stopped going to school because of corona. After the school closed, at first he was getting lessons on the telephone, but then those lessons stopped, and now he’s selling tissues on the street.”

Enrollment figures show a dropoff in the number of Syrian children registered in schools, while the number of Lebanese children attending public schools has increased dramatically as families who used to send their children to private schools have found themselves no longer able to afford tuition and other fees.

For the 2020–21 school year, 273,500 Lebanese children enrolled in public primary schools, up from 230,584 last year and 219,445 in 2018–19, the last full school year before the economic crisis and COVID-19 pandemic, according to statistics from the Education Ministry.

Meanwhile, the total number of Syrian children enrolled in public primary schools this year is about 190,600, down from 196,238 last year and 206,061 the year before. These figures include the Syrian students enrolled in specially designated “second shift” afternoon classes for non-Lebanese students, as well as a smaller number of Syrian children who attend regular morning classes with the Lebanese students.

While the number of non-Lebanese children enrolled in second shift classes has remained about the same — 150,000 this year compared with 153,286 in 2018–19 — the number of those enrolled in the “morning shift” alongside Lebanese students has decreased from 52,775 in 2018–19 to 40,600 this year.

Furthermore, Sonia Khoury, the head of the unit overseeing education for Syrian students at the Education Ministry, told L’Orient Today that more than 30,000 Syrian students who were previously enrolled did not return this year.

A student raises her hands in community activist Khaled al-Youssef’s class in Dalhamieh. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A student raises her hands in community activist Khaled al-Youssef’s class in Dalhamieh. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Even for those who are enrolled in school, relatively few have been able to attend classes. Last year’s vulnerability assessment of Syrian refugees in Lebanon by the United Nations found that only 17 percent of Syrian children aged 6–14 in 4,563 households surveyed had been able to take part in remote classes during the COVID-19 closures, largely due to lack of internet access.

A statement released Friday by Human Rights Watch characterized education for refugee children in Lebanon as being in “free fall” and noted that over the past two school years, they “have received almost no education whatsoever due to a failure by schools to provide them with distance learning.”

Even if they had internet access, as well as mobile devices necessary for distance learning, many Syrian students would not have the opportunity to attend, because the union representing second shift teachers has been on strike since early January over unpaid wages from last year. The union said in a statement that apart from payment of the delayed salaries, its teachers are demanding to be paid in dollars because the Education Ministry gets money from donor countries, who fund refugee education programs in foreign currency.

Khoury said the teachers’ payments had been delayed because the funds meant to pay them have still not been received.

“In the current financial context, the operating environment is highly complex. UNICEF is in negotiations with relevant stakeholders trying to ensure outstanding payments are made to teachers as soon as possible,” Yukie Mokuo, UNICEF’s representative in Lebanon, told L’Orient Today in a statement.

Child labor on the rise

As the number of dropouts increases, more children are going to work, driven by the lack of schooling and economic desperation.

“Because children are not in school, because access to learning is limited, the impacts on children are not limited to questions about learning,” Mokuo said.

She noted that increases in rates of domestic violence and child marriage as well as child labor have been reported over the past year. A lack of school “immediately increases those other protection risks as well,” she said.

While estimates vary regarding the percentage of Syrian children in Lebanon who are working, surveys have found that the numbers have increased. The UN vulnerability assessment found that the portion of Syrian children engaged in child labor among the 4,563 households surveyed rose from 2.6 percent in 2019 to 4.4 percent in 2020. A separate survey conducted by UNHCR in May 2020 found that 11 percent of 598 refugee households interviewed reported having sent children to work since October 2019, up from 5 percent the year before.

Many families have turned to informal education to provide what the public school system could not. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Many families have turned to informal education to provide what the public school system could not. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Nisreen Hamadi, a Syrian refugee from Idlib living for the past five years in the town of Bar Elias, has five children aged 6–16. All but the youngest have worked over the past year.

Hamadi told L’Orient Today she had never been able to register any of the children in public school, despite trying repeatedly.

“Every time I would go to register, they would tell me, ‘We’ve reached the maximum number’ or ‘There are no more spots,’” she said.

Instead, she enrolled them in a charity-run informal primary school.

Hamadi’s three eldest children have aged out of that school, while the younger two are taking lessons online. But because the family does not have Wi-Fi in the house and relies on phone data to access the internet, Hamadi said their ability to follow the classes has been limited.

Hamadi’s 13-year-old son, Abdallah, works in a bakery; his 15-year-old brother, Abdel-Karim, works overnight shifts in a potato chip factory. Their 12-year-old brother, Abdel-Majid, who is still attending classes with the informal school, also worked for a while in a car mechanic shop.

Their 16-year-old sister, Abir, who used to dream of becoming an attorney, used to work for a company exporting fruits and vegetables but quit because of bullying and harassment by supervisors.

“Of course I prefer for them to be in school,” Hamadi said. “It’s better for them because that will give them a future. If they don’t learn and get an education, they won’t have a future.”

But because they have no option to go to school now, she said, “the whole family has to work now to secure the necessities.”

Six-year-old Bisan, a daughter of Nisreen Hamadi, completes lessons for a charity-run informal school on a smartphone. Hamadi has five children, only two of whom are currently able to attend classes. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Six-year-old Bisan, a daughter of Nisreen Hamadi, completes lessons for a charity-run informal school on a smartphone. Hamadi has five children, only two of whom are currently able to attend classes. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Khaled al-Youssef, a Syrian community activist who has been carrying out informal education programs in some of the camps in the Bekaa, said that while the economic situation is a major driver of child labor in Syrian communities, the lack of school is exacerbating the problem.

“When there is no education, there will be child labor, and when there is child labor, you will usually find that this community is deprived of education,” Youssef said.

On a recent rainy afternoon, dozens of children poured into a large room that serves as both mosque and classroom for their camp in the Bekaa town of Dalhamieh. They sat in rows with a perfunctory attempt at social distancing as Youssef led them through the alphabet and numbers in Arabic and English, a series of arithmetic exercises, and recitation of verses from the Quran.

Some of the children had never been enrolled in formal schooling; others who were enrolled said they were not receiving online classes. Only one of the boys said he had been receiving lessons, over WhatsApp one or two days a week.

Return to learning

With a gradual reopening of schools likely on the horizon in the coming weeks, it remains an open question how many Syrian children will come back and how they will fare once they return.

For children who have been out of formal schooling for several years, the only way to enroll in public schools is to take a special accelerated course to help them catch up with their peers. But the ministry has not offered the program for the past two years, leaving those children without a path to return to school. Meanwhile, the ministry has also closed down a number of informal schools that were teaching without a license.

The children who were registered last year but did not re-enroll this year should technically be allowed to register without going through the accelerated learning program.

“We asked the partners to address the current needs of those children by keeping them engaged in learning until they are ready to be supported to enroll in the next scholastic year, and we have assured that this coordination should be done in early September ahead of the school year 2021–22 kick-off to guarantee their registration in the schools,” Khoury from the Education Ministry said.

But it remains to be seen how many will come back.

“Even before the crisis … we know that [Syrian] children were somehow struggling in catching up in schools, for the language support they needed or vulnerable children, children with disabilities,” said Alaa Hmaid, Save the Children’s education capacity building and development coordinator in Lebanon.

“Now after two years of not getting this service, and with all these crises happening in Lebanon, for sure children will face difficulties in returning to education.”