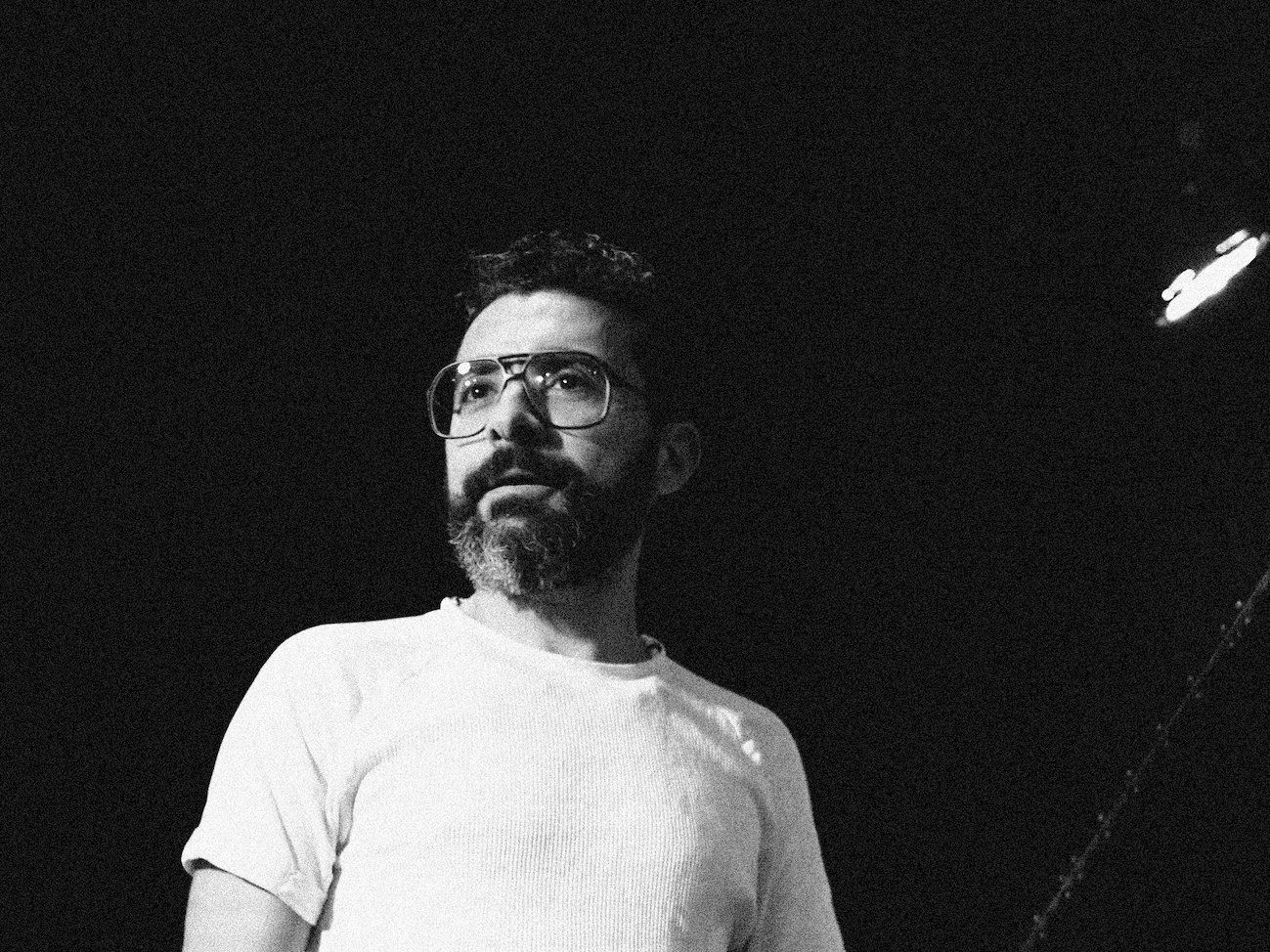

Tarek Yamani in concert. (Photo by Franzie Allen)

BEIRUT — “This is the tradition that I’ve spent my life studying religiously, daily, for a decade. This is my backbone.”

Pianist and composer Tarek Yamani is talking about jazz, in the tradition of luminaries like John Coltrane, Ahmad Jamal, Herbie Hancock, Wynton Kelly and Freddie Hubbard.

“I was determined to speak this language as they speak it, fluently,” he recalls. “Some people think you can’t because you’re not from there. I thought, ‘No, you can, just like someone can speak English fluently, though they’re not from there.’ You just have to do the work. You will still have your accent but you can speak fluently, and converse with native speakers at the highest level.”

Jazz has taken Yamani far, from his family home in central Beirut to New York and, more recently, Berlin. Since winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Composers Competition in 2010, the pianist and educator has released three albums, written and published two books and performed in a wide array of world-class venues — the Smithsonian in DC, New York’s Lincoln Center (including Dizzy's Club), Barcelona Cathedral at La Merce, Berlin’s Boulez, Dubai Expo 2020, and Gran Teatro de la Habana — the most prestigious of which may be his four International Jazz Day concerts since 2012, playing alongside such greats as Wayne Shorter, Richard Bona, Zakir Hussein and Esperanza Spalding.

Tarek Yamani during a gig at the Vertigo jazz club in Wrocław, Poland. (Photo by Lech Basel)

Tarek Yamani during a gig at the Vertigo jazz club in Wrocław, Poland. (Photo by Lech Basel)

Yamani launched his Beirut Speaks Jazz initiative in 2013 and oversaw its three editions. He still performs in Lebanon from time to time, most recently at Marsah, a new-ish cultural venue in Trablous’ Mina district, and he’ll have a pair of shows in Beirut on Thursday and Friday (March 7-8) at Hamra Street’s Barzakh café-bookshop. He’ll be playing his well-honed trio program with two frequent Beirut accompanists — double bassist Makram Aboul Hosn and percussionist Dani Shukri.

“The repertoire is mostly from my second album ‘Lisan al Tarab,’ a study on classical Arabic music, especially muwashahat [a vocal form from Andalusia with ample opportunities for improvisation], arranging them with jazz chords, jazz harmony, but not really disrespecting the melody.”

The set will also include original tunes. “This music is based on rhythms from here, so I have ‘New Dabke’ and there’s ‘Sama‘i Yamani’ [sami‘a being a vocal form particularly important in Ottoman Turkish Sufi music], for example. So I compose music based on these rhythms. I also have things that sound Arabic but they’re not — it’s just the modality or maybe the ornamentation. We’ll also play some jazz standards. We’re playing two nights, so we’ll maybe change it up a little.”

3aks al Ser to Sama‘i Yamani

Yamani got his start as a performer when he was a teenager, with pioneering hip hop group 3aks al-Ser (aka Aks’ser), founded by Rayess Bek and Eben Foulen.

Tarek Yamani during a show at Berlin’s B-flat jazz club. (Photo by Stefan Weber)

Tarek Yamani during a show at Berlin’s B-flat jazz club. (Photo by Stefan Weber)

“Nobody knows that I was in 3aks al Ser because I went by a sort of Chinese-sounding nickname, Fun Jan Shai [“glass of tea”]. I’m known to be a heavy tea drinker.” He laughs. “There was a period where they called me Sol Faj [solfège, music theory], because I studied music.”

Shortly after helping fuel Beirut’s hip hop revolution, Yamani caught the jazz bug.

“I quit everything else and just focused 100 percent on piano and understanding the language of jazz,” he says. “Then 12 years later I realized that I was ready to release an album.”

Two years after winning the Thelonious Monk prize, Yamani released “Ashur,” which he produced with renowned percussionist Khaled Yassine, his longtime friend and collaborator. The album mingles a few of the composer’s original pieces with jazz standards, including Bach’s Prelude no. II in C Minor, as rendered by an ensemble of piano, tuba and drums. Tracks like “Dabke In Eb Nakriz” and his Monk Prize-winning “Sama‘i Yamani” betray his enduring interest in interpreting MENA region melodies with jazz modalities. These interests persisted in 2014’s “Lisan al-Tarab” and 2017’s “Peninsular,” which explores Khaleeji (Arab Gulf) rhythms.

Yamani says his interest in the music of the Arabian peninsula stems, in part, from his heritage — his father’s family migrated from Jazan, a Yemeni town that has been Saudi since Riyadh annexed the province in the 1960s, but “Peninsular” grew out of more recent artistic and practical considerations.

Tarek Yamani in concert. (Photo by Sachyn Mital)

Tarek Yamani in concert. (Photo by Sachyn Mital)

“The percussion, the rhythms from the Gulf are very special in how they swing and how they groove,” he says. “They’re different from all the other rhythms that we know — either African or North African and definitely very different from Levantine rhythms ... After Khaled [Yassine] and I finished ‘Ashur’ he suggested why not do something with Khaleeji rhythms? It stuck in my mind but it took about five years to come together, when the Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation approached me with a commission.”

Tom and Jerry

Swing and groove are central to Yamani’s jazz interpretations of Arab-Muslim classical music. Though he says it was impossible to not be aware of an older generation of Lebanese musicians’ experiments with oriental jazz, his principal influences and training have been in the Western musical tradition, from pop music to jazz to classical. His first jazz encounters came early.

“I’d thought I discovered jazz when I was like 18 or 20,” he recalls, “but actually it was [the Hanna-Barbera’s cartoon] ‘Tom and Jerry,’ 100 percent. I remember being mesmerized by Jerry playing drums with this quintet in a jazz club, and the whole New York jazz club atmosphere with the red lights and bar and whatever. The music and vibe mesmerized me. I had no words to express or feelings to understand what this was, but it did something. In another episode Tom tries to seduce a lady cat, playing ‘Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby’ on the bass, while Jerry’s trying to sleep in the basement.”

Other contemporary musicians who have worked to harmonize classical Arabic music with jazz have stressed what the two forms share — the centrality of improvisation and, since the mid-20th century, modal jazz experiments of pioneers like Miles Davis, Bill Evans and John Coltrane. Yamani cautions that commonalities will take you only so far.

“There’s no one answer,” he says. “The two musics are worlds apart ... Improvisation is common, but it’s totally different. Arabic music is modal with a totally different concept of making emotional changes in the music. It doesn’t rely on harmony. It relies on melodic development. It relies on different kinds of emotions. In jazz, it’s more harmonic, it’s rhythmic.

“It’s really up to the chef who is cooking. If you know what you’re doing, you can masterfully combine these flavors in a way that, when somebody tastes it, it’s like, ‘Wow, I’m having an experience right now.’ My tongue is experiencing a palette of new flavors but it’s not bothering me. It’s not making me feel confused. It’s a third experience.

“When you create an experience, it doesn’t make you feel that you’re combining two things at the same time. It becomes one. I think that’s the secret.”

Tarek Yamani and his trio will perform at Barzakh café-bookshop Thursday-Friday. Doors open around 8 p.m.