Kees Van Dongen. “Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock,” 1961, oil on canvas, left; catalogue reproductions of Sursock’s portraits, right. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

BEIRUT — From the far side of the gallery a strident, static-laden voice coughs up a word or two.

“I think the [tropes] of rebirth and renaissance that surround the Sursock museum have been on repeat since it was founded,” says Natasha Gasparian. “What was really striking to us in the archives is how artists seemed ill at ease with it, this space that became a museum, that was and still is the villa of Nicolas Sursock.”

Opening his bottle of water, co-curator Ziad Kiblawi nods, sips and screws the stopper back on.

“Traces of Sursock are frequently reproduced,” Gasparian adds, nodding to Kees Van Dongen’s 1961 portrait of Sursock, recently restored by Centre Pompidou. “His spectral presence sort of haunts the place.”

She gestures to the six miniature reproductions of Van Dongen and Philippe Mourani’s earlier portrait of Sursock, which routinely adorned the catalogs of the Salon d’Automne, the museum’s signature seasonal exhibition.

Mohammad Sakr. “Le monde de l’artiste,” 1966, oil on canvas. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

Mohammad Sakr. “Le monde de l’artiste,” 1966, oil on canvas. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

“This was the starting point for us,” she says. “The technological reproducibility of Sursock’s image did not result in the decay of his spectral presence. It helped preserve it.”

A uniformed security guard, one of two monitoring the museum’s collections galleries, stomps up and peers at L’Orient Today’s reporter, currently thrusting his phone at the two curators’ faces. He steps closer, pauses tentatively, turns on his heel and returns to his colleague, whose walkie-talkie barks up another emphysema-ish blart.

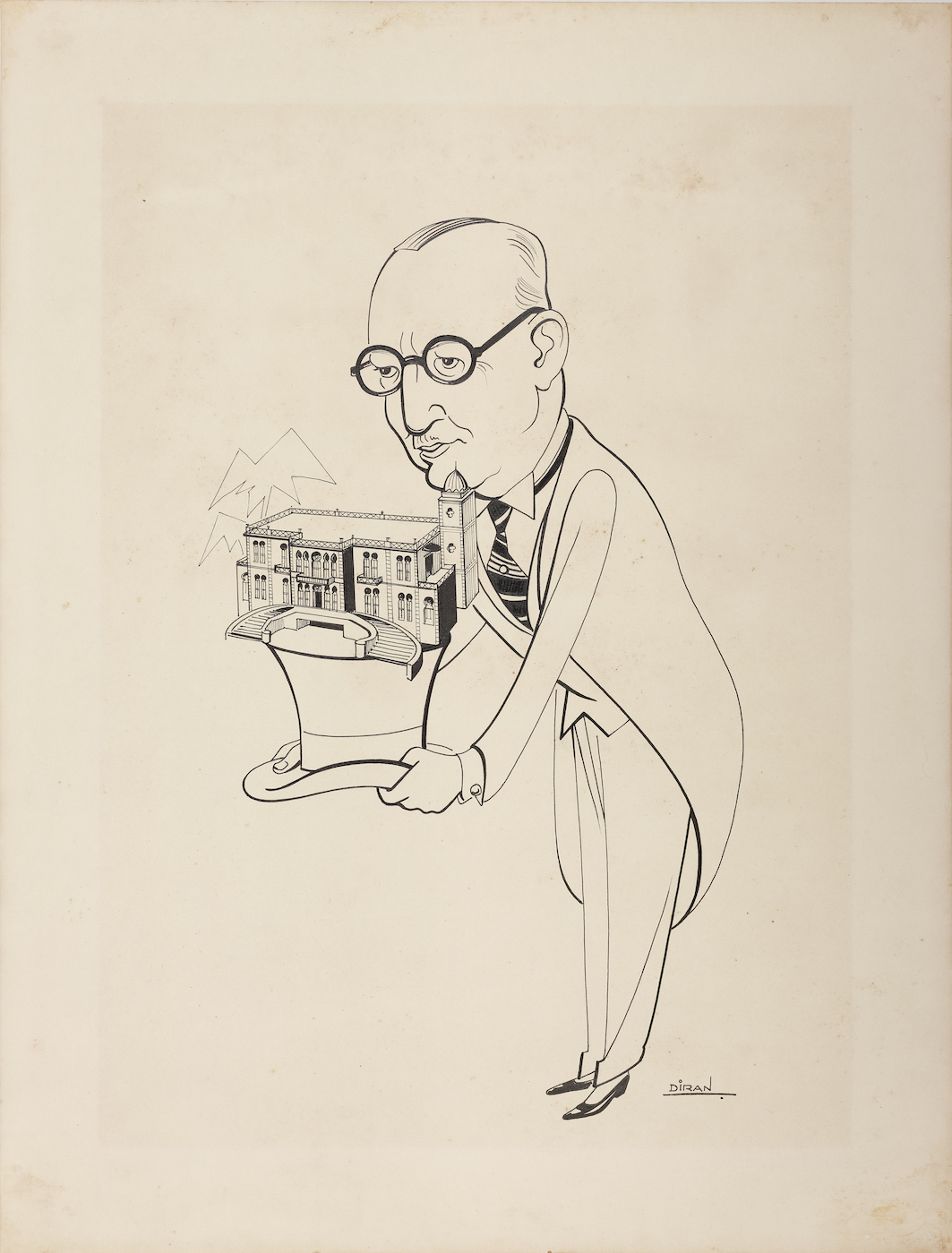

Gasparian pauses beside one of the collection’s donations, a pen-and-ink cartoon by Diran Agemian from 1961, titled “Nicolas Sursock offering his private mansion on his top hat.”

“This caricature is poking fun at Sursock,” she observes, smiling briefly. “As you can see, there’s no one to receive the offering, so it’s unclear who the museum is for.”

The security guard returns with his colleague, who mutters a discreet word at the curators. They blink at him and hand over the water bottles they’d been clutching.

“Malesh,” the security man smiles, placing the bottles on the floor nearby. “Don’t worry about it.”

His colleague scoops them up and carries them back to the far corner of the gallery.

It’s clever of Sursock to stage a contemporary art performance in the midst of an exhibition showing work from his modern art collection.

There was anticipation in the air on this last Friday of May 2023, as two cultural institutions roused themselves for the Beirut public. It isn’t common to hear “Metro al-Madina” and “Sursock Museum” uttered in the same breath, but they cohabit the city’s diverse and segmented arts sector. After three years of financial crisis, economic collapse and administrative indolence — seasoned with deadly global pandemic and unnatural disaster — that sector is depleted and emaciated. It’s also stubborn, as the events of May 26 suggest.

The calm before the music

It is Friday afternoon. A hush clutches the Sursock Museum’s interior rooms. In the ground-floor vestibule, a harried staffer channels a trickle of journalists toward various appointments.

Black-clad young vocalists and musicians linger on the museum’s front steps while technicians fiddle with the PA system. Before them, the museum esplanade is crowded with rows of plastic chairs, awaiting the bums of guests assembling to witness the official reopening. This will include speeches from some of the many international donors and partners who pitched in to help restore the damaged villa and its collection. Intermittent events aside, the Italian-inflected Ottoman structure has been shut to the public since the Beirut port blast of Aug. 4, 2020.

Diran Agemian. “Nicolas Sursock offering his private mansion on his top hat,” 1961. India ink on paper. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

Diran Agemian. “Nicolas Sursock offering his private mansion on his top hat,” 1961. India ink on paper. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

In the collections galleries, Gasparian and Kiblawi stand amid their exhibition “Je suis inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the National Canon,” one of five separate shows scheduled to open at Sursock this day.

To mark the museum’s 60th anniversary in 2021, Sursock’s then-director Zeina Arida commissioned a show from the permanent collection. Now installed, “Inculte!” uses Lebanese artists’ work (most of it from Sursock’s permanent collection) to illustrate the seminal debates that have shaped the museum’s history.

Taking its name from Jalal Khoury’s 1964 article “Je suis inculte!” (I am uncultivated!) — which excoriated Sursock’s elitist bias toward abstract art — the show interrogates the five roles that local narrative conventionally ascribes to the museum and its Salon d’Automne: forging Lebanon’s artistic canon; offering an exhibition model for the newly independent state; providing an academy for training young artists; refining the tastes of the domestic public and, as a de facto public institution, reflecting the state’s several crises — most conspicuously Lebanon’s Civil War.

“There’s a strong sense that the museum is an elitist institution,” Gasparian explains. “We were interested in probing that sentiment by taking seriously the Salon d’Automne’s role in forging a national canon. [We also wanted to see] why that created so much tension — particularly after 1964, when the museum started bringing in juries and awarding prizes.”

As they lead this journalist through the show’s several chronologically ordered components, the curators touch upon the museum's relationship to the Sursock family (particularly Lady Yvonne Sursock-Cochrane) and the cosmopolitan merchant-landowning class to which they belonged, its francophile leanings and selective patronage of local artists.

“Jury members were often quite well situated in the Parisian art scene,” Gasparian notes. Figures like critic, art historian and Paris Biennale juror Jean-Jacques Lévêque facilitated several Lebanese artists’ participation in the Paris Biennale.

“In this part of the show, we’re trying to focus on the strong link between the Salon d’Automne and Alba [Balamand University’s Académie Libanaise Des Beaux-Arts. Most of the regulars were Alba students or instructors.”

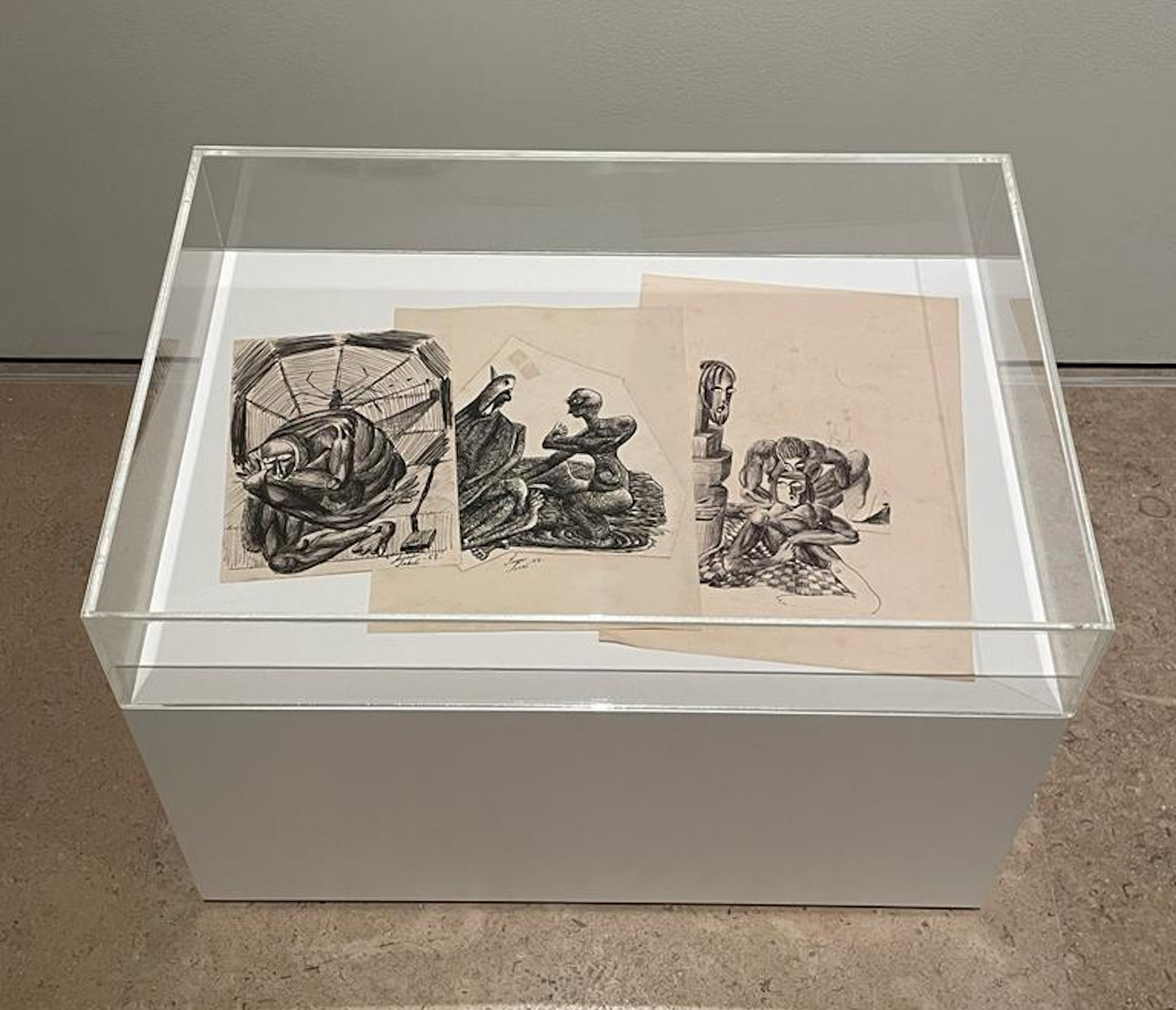

Issam Sabaa. “Prisonnier,” “Conversation,” “Quatre,” 1968, graphite on paper. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

Issam Sabaa. “Prisonnier,” “Conversation,” “Quatre,” 1968, graphite on paper. (Courtesy of The Sursock Museum)

“While the salon has this strong symbiotic tie to Alba,” Kiblawi adds, “Lebanese University’s institute of fine arts is largely absent.”

Sursock’s role in forging a national canon was accentuated because the country did not, and does not, have a national museum of modern art.

“A national museum project had been planned,” Gasparian notes. “Several prominent artists, like Aref El Rayess, were involved in it, as was the minister of finance and education at that time, but the project never panned out. In the absence [of a national gallery] Sursock is, for better or worse, Lebanon’s only public institution devoted to modern art.”

The curators suggest that, while the museum’s Salon d’Automne played a serious role in patronizing Lebanese artists, it didn’t dictate the national canon.

Gasparian nods at a painting by Mohammad Sakr. Rendered in hues of yellow and brown, it might be an impressionistic depiction of a rickety latticework of footbridges.

“Sakr was once a quite prominent artist,” she says. “There’s an anecdote that [cinema writer] Joseph Tarrab shifted his focus to painting after seeing Sakr’s work. In the archive, we found Sakr had many important solo shows. Lady Cochrane supported him and worked to find him a scholarship to study abroad. His works were displayed at the Salon d’Automne and several of them were purchased by [New York banker] David Rockefeller, who had interests in Lebanon’s banking boom in the 1960s. Sakr has since been cast into oblivion, and never quite makes it into discussions of the national canon.”

“Then,” Kiblawi says, “we have this lovely find.”

He pauses alongside a vitrine housing three works on paper by Issam Sabaa, all dated 1968, titled “Quatre,” “Conversation” and “Prisoner.”

“No one had ever heard of Issam Sabaa,” Gasparian says, recalling how, several months into her research for this show, she stumbled upon Sabaa’s works among rejected Salon d’Automne submissions.

“As an artist, you would have to submit your works for the jury’s scrutiny,” she adds. “If you didn’t pick them up afterward, the museum kept them. These pieces are in the museum’s collection because he never came to collect them.

“We don’t really know anything about the artist except that he put down his address as Burj al-Barajneh,” a municipality south of Beirut that hosts the Palestinian refugee camp that takes its name. “While we cannot say he was rejected because he was Palestinian, the rejection is curious to us [because] there is some congruence between the style of Sabaa’s works and the museum’s support for and encouragement of surrealism.”

“Je suis inculte!” deploys Sursock’s diverse collection in a serious critical discussion of the museum’s place on Lebanon’s art history landscape. Among the charms of the show is the contemporary sensibility driving the curators’ selection and — when encountering gaps in the narrative — the energy with which they leaven the archive with educated guesswork, nudging the show toward speculative history.

As L’Orient Today’s reporter departs Sursock Museum, the plastic chairs have been filled, leaving many to stand while listening to the speeches. A few moments later, the strings are struck and the strains of Vivaldi’s choral work Gloria in D major leap from the esplanade.

“Gloria in excelsis Deo!”

The Mehania ensemble opens Metro’s fundraising party with a set of crowd-pleasers, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

The Mehania ensemble opens Metro’s fundraising party with a set of crowd-pleasers, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

Music rises from Aresco’s underground

Clearly, Metro al-Madina has moved up in the world. It’s only fitting for an entertainment venue named after a form of underground locomotion to have a subterranean space but, while the first Metro station at Masrah al-Madina’s sub-basement in Hamra was at -2, Aresco’s Clemenceau/Qantari stop is at -1.

Renovations to Aresco Palace’s theatre are not quite finished. Curtains have been hung, the stage and sound system are in working order and the bar is adequately stocked and manned but the metal rails that discipline the terraced seating area may require some shoring up. The ceiling too seems to disclose more than necessary, but any habitué of Saroulla’s little theatre, Metro al-Madina’s original home, would be less struck by the venue’s warsheh than by its height and depth.

Half an hour before showtime some of those Saroulla habitués mingle among less familiar faces in soaking up the ambiance. Aside from a few pairs of footrest-style things (aka “poofs”) and the edges of the terraces themselves, it’s standing room only this evening. Over its 11 years of performances, the cabaret’s public is usually seated at tables but these are routinely cleared away for events with high audience demand.

When the music begins, sometime after 9:30, some on the terraces look around, trying to find the performers, as the stage is still vacant. Those queuing for drinks are better positioned.

Aimed left of the bar, the stage lights illuminate a sextet performing a set of tarab-ish tunes from the 20th-century — “Tango El Amal,” for instance, and “Helif El Amar” — famously performed by vocalists like Nour El Mallah (b. 1924) and George Wassouf (b.1961). None of Metro’s players are of Mallah’s vintage and these musicians, particularly the reserved vocalist Asmaa Arayshi, have a 20-something sheen about them.

Sandy Chamoun performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

Sandy Chamoun performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

She, along with percussionist Abed Arayshi, Chadi El Ahmadieh, keyboards, violinist Raphael Haddad, saxophonist Taym Safsafi and Raas Shhuf, oud and cello, are all part of Mehania. Metro’s training program for young performers, Mehania is dedicated to sharpening the skills of young actors, vocalists, musicians and the like and diversifying their skill set to make them more rounded performers. It’s a unique initiative that mentors aspiring performers while broadening the cabaret’s talent pool.

The final shows at the Saroulla space were staged at the end of 2022. The troupe has broken its hiatus to stage a benefit show that, it is hoped, will help lure financing to complete the venue’s renovations and help finance operations.

Repertory theatres like Metro, which stages shows most nights of the week, are expensive to operate. They combine a bar-restaurant’s overhead with that of a working theatre — salaried performers, songwriters, technicians and the expenses entailed in producing original work.

For most of its existence, Metro’s budget has come from box office and bar sales. It’s an entirely different business model from a legacy institution like the Sursock Museum, whose financing is premised on a currency stream from Beirut municipality (rendered hypothetical since Lebanon’s financial collapse), which could rely on international assistance in the wake of the port blast — though AFAC and Culture Resource have offered financial support to both Metro and Sursock since the financial crisis.

As the Mehania players complete their set, the spotlight moves to the main stage, where it finds the figure of Roberto Kobrousli, Metro’s indefatigable MC, the onstage persona of cabaret cofounder Hisham Jaber. Bursting through the curtains, Kobrousli sports a new look, having shed his array of colorful tuxedos for what might be a silver lamé shirt whose plunging neckline rivals that of any ’70s-era glam rocker.

Kobrousli’s stand-up is brief and, in the tradition of Metro’s standing-room-only year-end parties, he devotes part of his act to some joke-inflected reflections on the state of the Metro. Partnerships, he smiles, are welcome.

Yasmina Fayed, right, performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

Yasmina Fayed, right, performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

The balance of the show features two ensembles mingling the cabaret’s veteran performers with its younger talent.

Metro’s most admired female vocalists (Yasmina Fayed, Sandy Chamoun and Cosette Chedid) join a band whose personnel are familiar from shows like Hishik Bishik, Bar Farouk and Metrophone, here performing a program of tunes by Sayyed Darwish — whose lyrical evocations of the disenfranchised has made him a favorite among Metro’s public. Oud player and vocalist Ziad El Ahmadieh is joined by Firas Andary, Deiaa Hamza, Farah Kaddour, Mazen Malaeb and Ahmad Khateeb (on vocals and fiddle, accordion/harmonica, buzuq and percussion, respectively).

For the third set, Andary removes his tarboush and takes center stage in “Hezz Ya Wezz,” drawing on a crowd-pleasing repertoire of historic Egyptian pop tunes and fronting a second ensemble — accordionist Samah Boul Mona, Khaled Houhou on keyboards, violinist Raphael Haddad, bassist Chadi El Ahmadie and percussionists Majdi Zeineddine, Bahaa Daou and Ahmad Khateeb.

For unknown reasons, there tends to be all kinds of audience embracing during these shows, but it’s oddly joyous this evening. En route to the toilet, you twice have to divert course to avoid the hugging laughter of people who haven’t seen each other in an age — maybe since popular demonstrations morphed into teargas, lockdowns and penury.

Other perils await. Standing at the bar, patiently waiting for one such clutch to disperse, some fellow, a Beiruti who left town years ago for points west, may stage-whisper into your ear from behind, “Thought I might find you here.”

He or she may wheedle you to retreat outside for a smoke. On the stairs leading up to street level, not far from the sign that reads “Arab Image Foundation” — another institution that’s in the midst of relocating to Aresco, partnered with the resuscitated Dawawine bookshop — a couple of once-young visual artists may laugh, then protest that they’re actually happy to see you’re still around.

Further up, you encounter dozens of patrons who’ve ascended to have a seat and take some air. Arrayed in clusters, laughing, the cool kids — unsoiled filters hanging from the bottom lip — tailor their darts from pungent tobacco wrapped in Waraq al-Sham.

Such a team photo it would make, you might say, fumbling for your phone. But no. The performers are on stage.

Cosette Chedid performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)

Cosette Chedid performs a tune from the Sayyed Darwish songbook at Metro’s fundraising party, May 26 at Aresco. (Credit: Lara Nohra, courtesy of Metro al-Madina)