nurse and a patient talk at Rizk Hospital in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Eyeliner applied with surgical precision, rosy cheeks, flawless complexion.

Despite her efforts, Nana’s dark circles are barely covered by her makeup. This mother of two teenagers, 15 and 18 years old, waits for the hours to pass in a room at LAU Medical Center-Rizk Hospital in Beirut. After the five-hour-long chemotherapy session is over, Nana has to go to work at the hair salon.

The 50-year-old mother leaves her house daily at 7:30 a.m. and is rarely back before 8 p.m.

Despite the fatigue, nausea and vomiting, she cannot rest.

“I have to provide for my family,” said Nana, who was diagnosed with breast cancer six months ago, without batting an eye.

A few days ago, she failed to pay part of her daughter’s school fees. “All the medications and vitamins I have to take to overcome the side effects [of the treatment] leave me without enough money. Because of that, she couldn’t get her school report book … It broke my heart,” she said.

Her salary and that of her husband are barely sufficient to cover the bills that are piling up.

“But my husband’s company covers my health insurance, neshkor Allah [thank God],” she said with a smile.

At home, Nana does her best to protect her children from the uncertainties related to her illness and the situation in the country.

“Haram, it’s not their fault, you have to encourage them, even when they see your hair falling,” she said.

At both Rizk Hospital and the government-run Rafik Hariri Hospital in Beirut, cancer patients recount another side of the crisis, one where subsidized cancer and chronic disease medications are even harder to obtain than money trapped in Lebanon’s commercial banks.

As they fight cancer, patients go into debt, chase NGOs for help, appeal to their relatives abroad for support and sometimes even turn to political parties.

‘This disease is such a pain’

In the same hospital room, Siham receives a call from her son.

“Don’t worry, sweetheart, I’m in excellent company,” she reassured him, in reference to Nana and another woman, Rita, her mates for the day. Every two weeks, Siham has to go to the hospital to get her treatment “which lasts for hours,” she said.

“This disease is a pain for you and your loved ones. What did I do to deserve this?” she said with tears in her eyes.

A nurse checking Siham's infusion at Rizk Hospital, Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A nurse checking Siham's infusion at Rizk Hospital, Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A lymphoma patient, Siham was close to ending her treatment due to shortages of subsidized medication. The latter are financed by Banque du Liban (BDL), whose foreign currency reserves have hit a critical threshold.

“I didn’t want my children to help me,” said the mother, who had initially thought she would hide her illness from them because she did not want to be a “burden.” Her children, based in Canada and Dubai, insisted on paying for her treatment.

Officially subsidized but unavailable, they had to pay market price for the medication.

“They paid thousands of dollars … It hurt me, they have a life and a family abroad,” Siham said, bursting into tears.

In spite of everything, Siham is one of the “lucky ones” who still has the means to get by. Others have no choice but to wait, at the risk of jeopardizing their treatment. The situation reflects the inequalities of a two-tier health system.

“To diagnose cancer is one thing, and to tell the patients that we don’t have the medication to treat them is a totally different thing,” said Dina Moutran, a clinical coordinator at Rizk Hospital.

Rita paid the price for this shortage. For a year, the 50-year-old woman tackled an obstacle course. The breast cancer patient managed to obtain medication through Turkey and Egypt at respective costs of $2,000 and $1,000.

“I borrowed money,” she said. Her husband earns a modest salary as a driver, and she had to give up her job because she also suffers from Parkinson’s disease. Every night, she wakes with fear. “I think about my next session and the possible shortages, my children’s school fees. You sleep and wake up anxious…” said Rita, whose physical health, she says, is improving.

The Lebanese medical sector, known until a few years ago as “the hospital of the Middle East,” is now a shadow of its former self. In the examination room of Dr. Hady Ghanem, head of the hematology and oncology division at Rizk Hospital, the word “hope” is written on the wall behind his desk.

“We are in a terrible situation,” he told L’Orient-Le Jour. “Sometimes we have had to change or delay treatment, [or] divide the dose between two patients … We see the health of some patients deteriorate when they initially had good results,” he explained.

A two-month delay

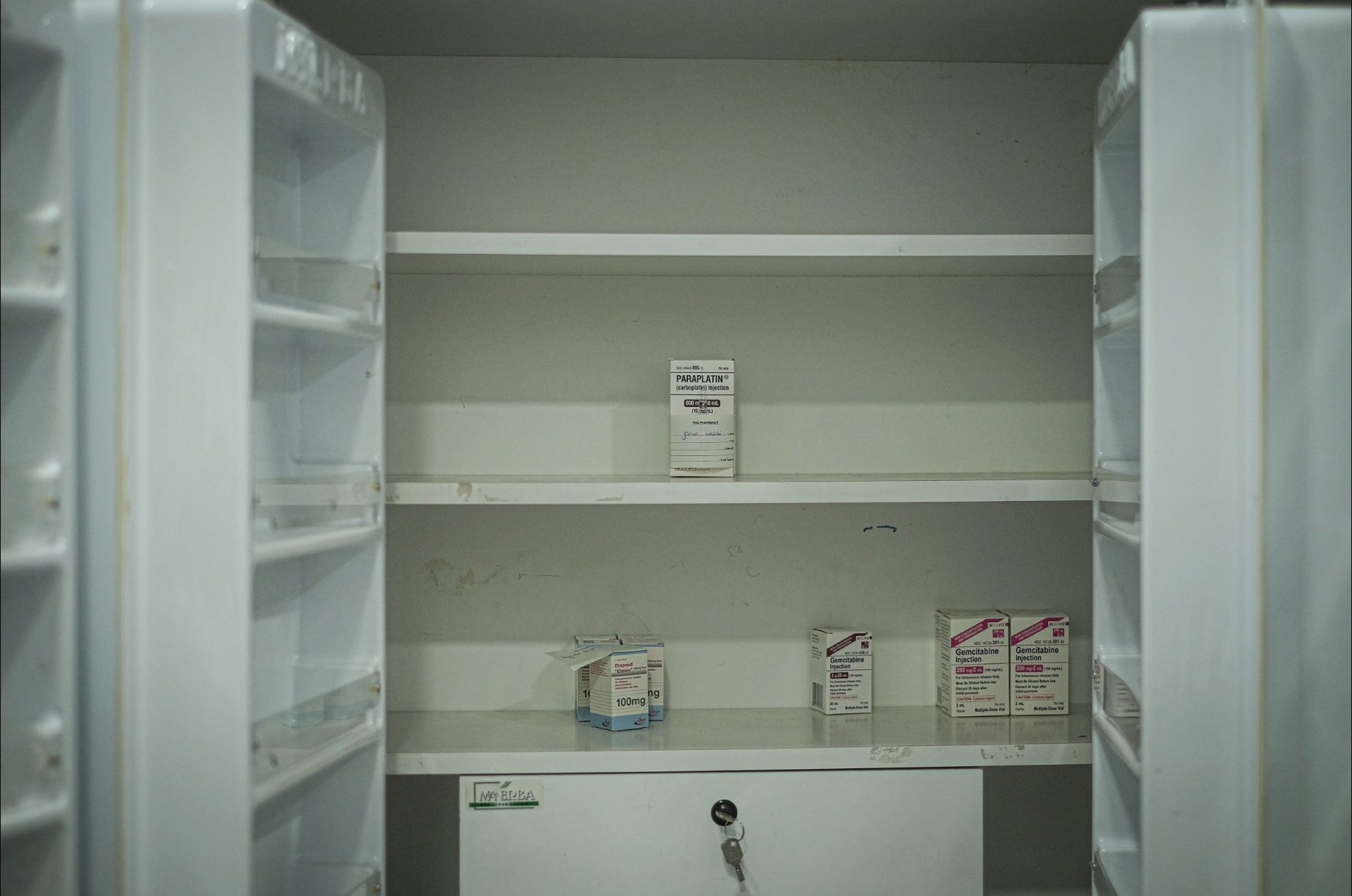

At Rafik Hariri Hospital, one of the cupboards in the pharmacy where chemotherapy drugs are prepared is almost empty. Although the Health Ministry recently launched Meditrack, a platform designed to ensure the traceability of subsidized cancer and chronic disease medication, and prevent them from being stockpiled and smuggled, the nursing staff at Rafik Hariri Hospital told L’Orient-Le Jour that delays in receiving the placed orders continue to be a problem.

A nearly empty cupboard in the pharmacy department of the Rafik Hariri government hospital, where patients' chemotherapy drugs are prepared. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

A nearly empty cupboard in the pharmacy department of the Rafik Hariri government hospital, where patients' chemotherapy drugs are prepared. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“This morning, a man burst into tears when we told him that we did not receive his medication. He had a surgery two months ago and is still waiting to start his treatment,” said Raida Bitar, head of pharmacology at Rafik Hariri Hospital, her voice breaking.

On the next floor, in the dark corridors of this public hospital, Wissam’s father says the rosary. His son, with a sunken face, is huddled in his winter blanket on his hospital bed. Wissam, 29, who worked at the Motor Vehicle Inspection Center in Hadath, was the sole provider for his family. He struggled to cover the cost of his leukemia medication even before the crisis.

“Then, with the shortage, he went a year without treatment,” said his sister, Rana. During that time, Wissam’s health deteriorated.

After more than seven months of hospitalization, he has just finished a course of chemotherapy. He is currently under observation and will soon undergo a transplant that will cost between $50,000 and $100,000. The family was able to secure some of the funds needed through a fundraiser.

“Why do we have to go through this?” Rana asked.

Like many Lebanese, Rana directed her anger at Lebanon’s politicians — all except one. The family receives help from a political party.

“The Progressive Socialist Party [PSP] has been supporting us for a year, they even paid for the delivery of Wissam’s wife [the birth of Wissam’s child] a few days ago,” Rana said.

Two children in the pediatric cancer ward. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Two children in the pediatric cancer ward. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

‘We still end up in debt’

In the pediatric department at Rafik Hariri Hospital, Taim and Maisa, two 4-year-olds who have leukemia, sit on their hospital beds.

“Why are you shy?” Raghida, Maisa’s mother, asked her daughter as she played a video of her singing and playing with her hair before she got sick.

To the girls families’, the cost of transportation to the hospital is the most worrisome. Raghida pays more than LL1 million each time she makes the trip. Taim’s mother, Iman, pays LL700,000 to travel from Tripoli to Beirut every week.

“We used to live in Akkar, but we moved to a smaller apartment in Tripoli so the transportation would be cheaper,” explained Iman. “I don’t know how I’m going to keep coming here.”

Imam explained that her husband works multiple jobs to cover the expenses, but that the family still “ends up in debt.”

Just next door, Rola, the nurse, hugs her 17-year-old “darling” Ali.

“Look at this beautiful boy,” she said. The teenager has a tumor in his knee. While his medical expenses are covered by the army, in which his father serves, he too has sometimes had to source medicine from abroad at high prices.

“I am afraid that all this fatigue [as a result of the treatment] will lead to nothing. The day I stop getting my medicine, I’ll have to stop the treatment,” Ali said.

Meanwhile, he contemplates which will take a heavier toll on him: his illness or the country’s economic state.

“I can’t even buy a bag of chips because the transportation is costing me a fortune … The crisis is leaving me more tired than the cancer itself,” Ali said.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.