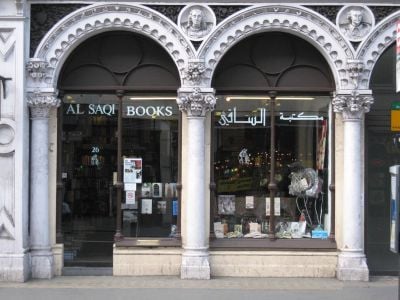

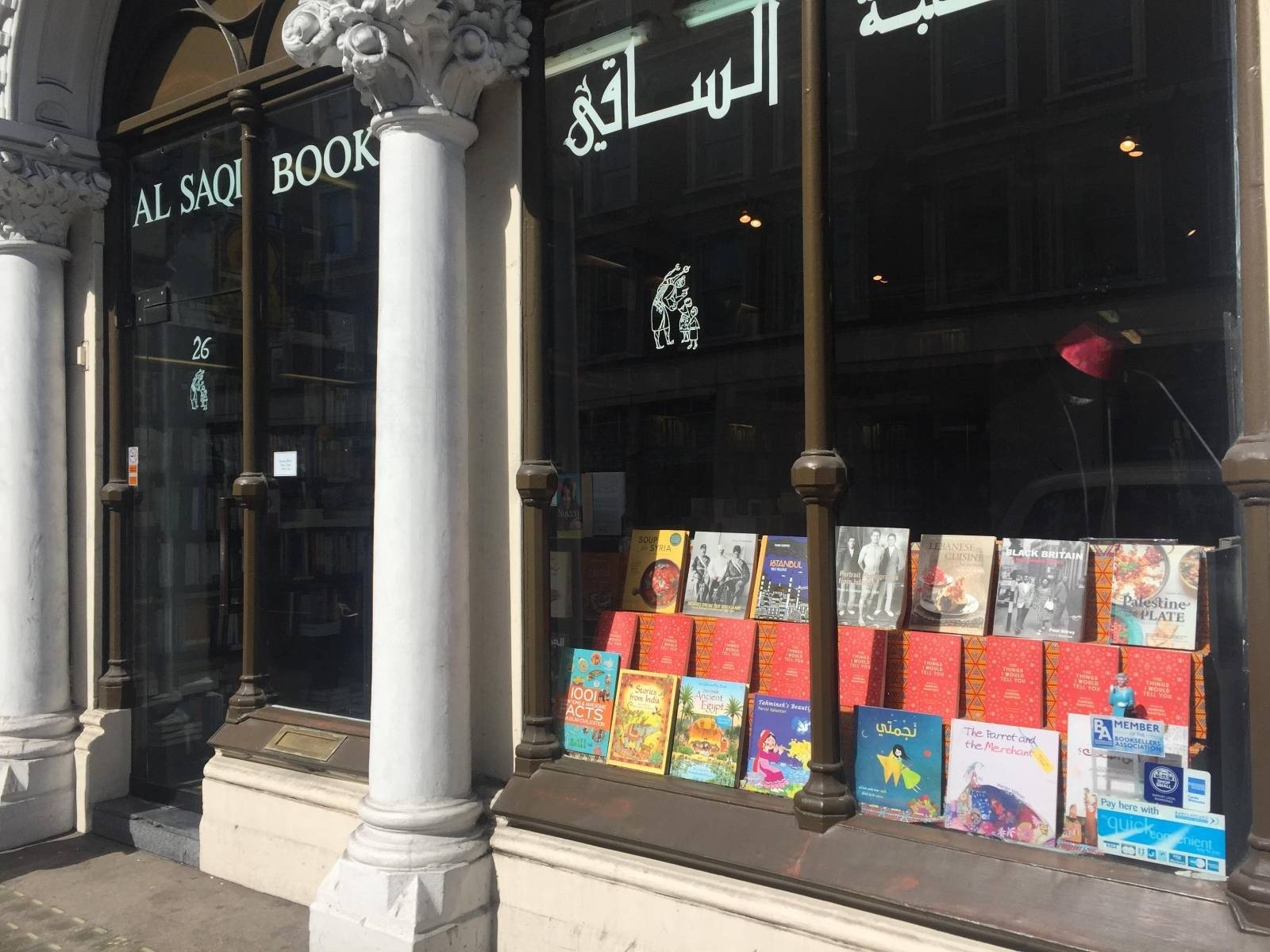

The storefront of Saqi Books in London, on the day of its closure, Dec. 31, 2022. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/L'Orient Today)

LONDON — “No, please! Can I just come in for one last look?” an exasperated customer exclaims in Arabic while knocking on the door of London’s Saqi bookshop. A young bookseller, Mohamad Massoud, gently tells the man that the shop is really closing. For good. It’s befittingly gray and gloomy on this last day of 2022.

Salwa Gaspard, a woman with big curls and an even bigger smile, is animatedly chatting with her last customer, a young woman who leaves with a big stack of books. When she spots me (I managed to sneak in), she starts telling me that the shop is closed, but then she suddenly stops and says, with glittering eyes: “Are you Lebanese? You’re wearing a cedar,” referring to the golden pendant peeking out from under my jacket. As if scripted, the bittersweet voice of Lebanese icon Fairouz softly serenades us while we chat a bit about Lebanon and loss.

Gaspard seems rather subdued. The shop is closing, there’s a lot to do and it’s New Year’s Eve. We agree to chat at a later, less hectic and heartbreaking, time.

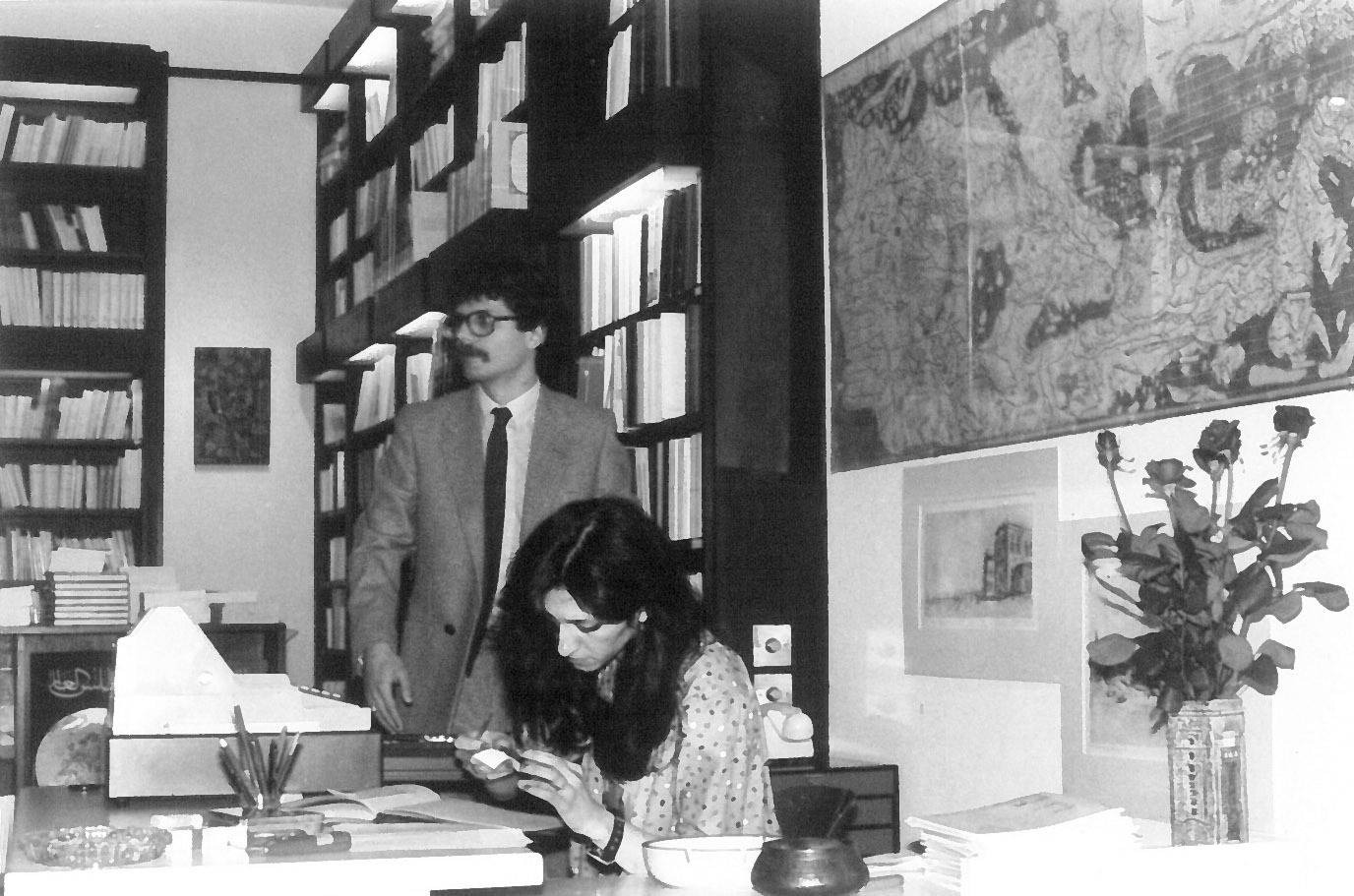

A few days afterward, Gaspard tells me about Saqi’s humble but serendipitous beginnings. The idea to start a bookshop was conceived by the late writer and artist Mai Ghoussoub, Gaspard’s husband André’s childhood friend, while growing up in Beirut. When she moved to London in the 1970s, Ghoussoub noticed that there was a large community of Arabs yet no Arabic language bookshop or any kind of cultural center. She excitedly called both Salwa, who was studying in Paris at the time, and André, who was living in the United States, and in 1978 they decided to take a leap into the unknown and open Saqi in Notting Hill.

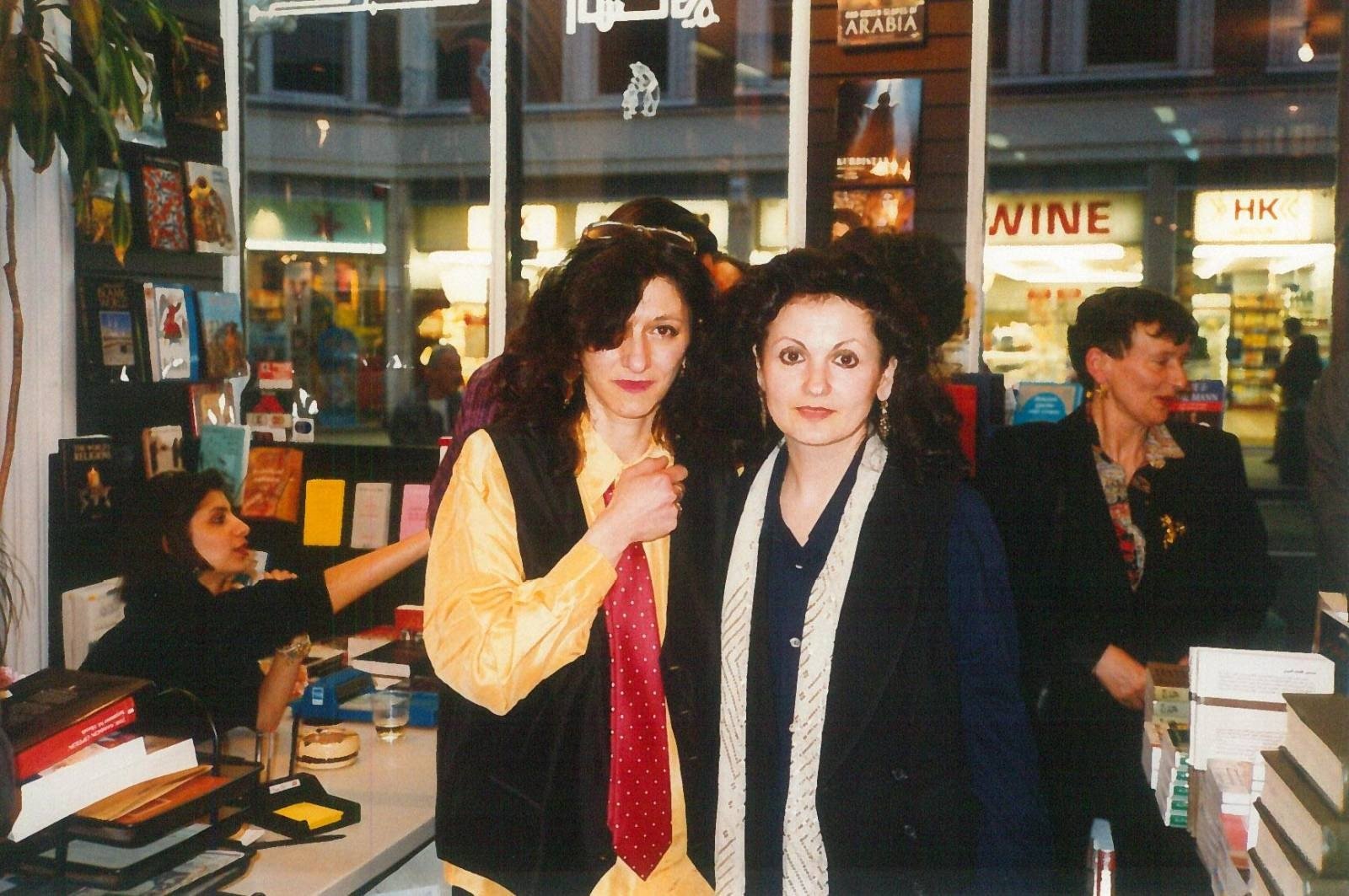

Al Saqi founders André Gaspard and Mai Ghoussoub in the late 1970s. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Al Saqi founders André Gaspard and Mai Ghoussoub in the late 1970s. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

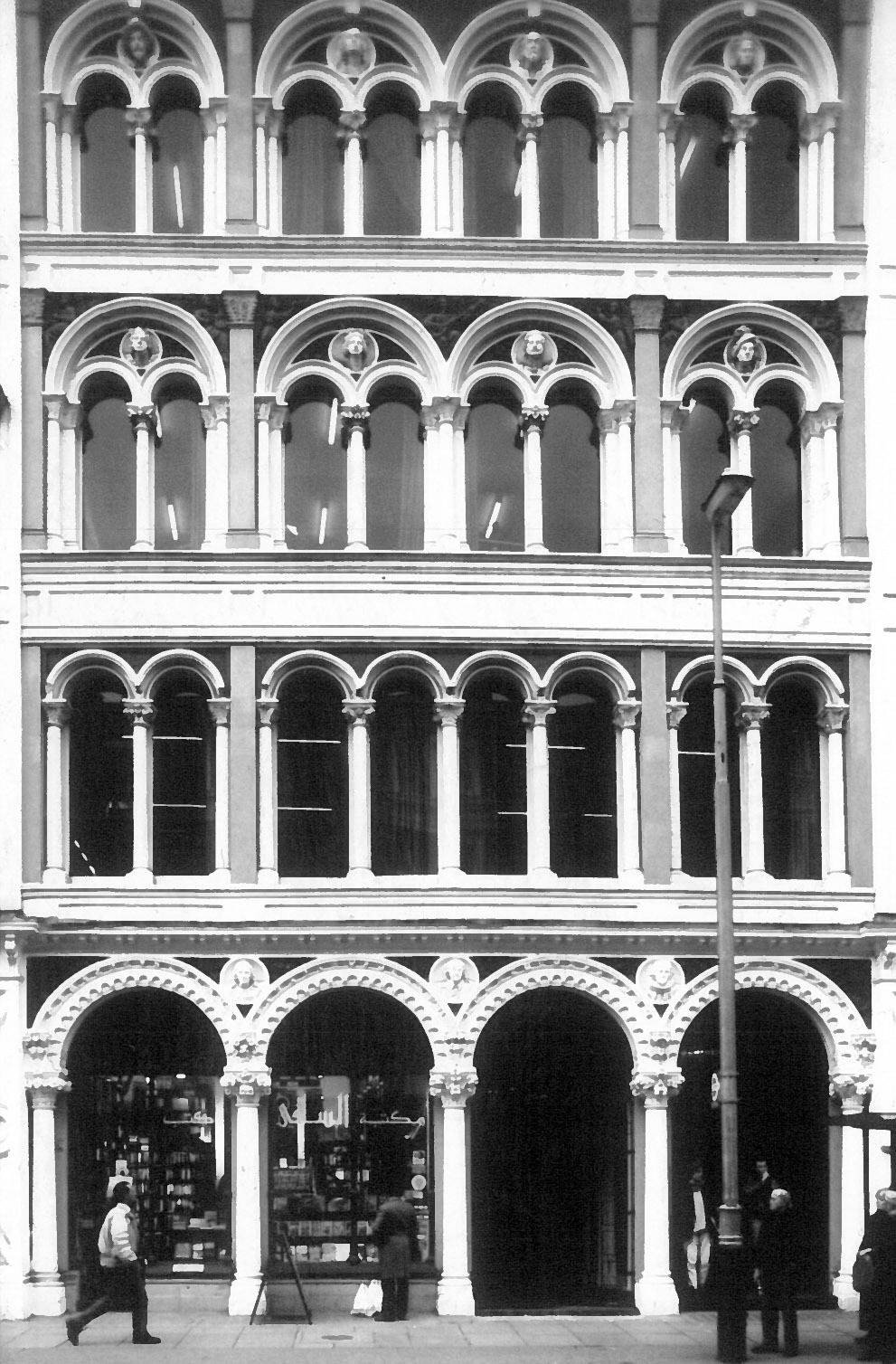

The trio, armed only with a profound love of books and a bittersweet nostalgia for the Arab world — particularly Lebanon — which they had been forced to leave behind, chose the name Saqi, which means water seller. The name (and logo) refers to a famous eponymous painting by Iraqi artist Jawad Selim and signified that the shop, rather than just books, would sell culture — that other fundamental human nourishment. In 1983, Saqi launched a publishing arm, Saqi Books, followed in 1990 by its sister Dar Al-Saqi publishing house in Beirut, the warehouse of which was bombed by Israel in the 2006 war. The publishing houses remain open.

Salwa says she was the first of the trio to leave Lebanon in 1974, the year before the Civil War broke out, to study in France. It wasn’t because she had a premonition of how bad things were about to get. But things were already bubbling under the surface, she says.

Arab migration to London greatly increased in the 1970s, mainly due to accumulated wealth in the oil states after the oil boom, and the Lebanese Civil War. The influx of Arabs included many writers, journalists and publishers, who could not only turn to Saqi for books in their native language but also a sense of community and, as Salwa puts it, “a place of freedom with a complete lack of censorship.”

Sudanese author Leila Aboulela in front of a display of her short story collection, "Elsewhere, Home," 2018. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Sudanese author Leila Aboulela in front of a display of her short story collection, "Elsewhere, Home," 2018. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Saqi was known to harbor a collection of books censored in some Arab countries, and some customers would specifically visit Saqi to have a look at these banned titles. Unfortunately, being a beacon of free speech did not come without consequences: after the shop displayed a copy of Salman Rushdie’s controversial The Satanic Verses, the window was smashed in. After that, they made sure to never display any books of a sensitive nature in the window, to protect employees and customers. But the banned books never disappeared from the shelves inside.

While Salwa, who took over management in 2007 after Ghoussoub passed away at age 54, humbly insists that Saqi did not necessarily “make a difference,” as I suggest, others beg to differ.

In a 1990 piece published by The Nation, on the state of translated Arabic literature, the late Edward Said writes that, when a New York publisher asked him for recommendations on “Third World” literature deserving of translation, yet ultimately decided not to translate future Nobel-Prize winning Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, that the reason given had haunted him ever since.

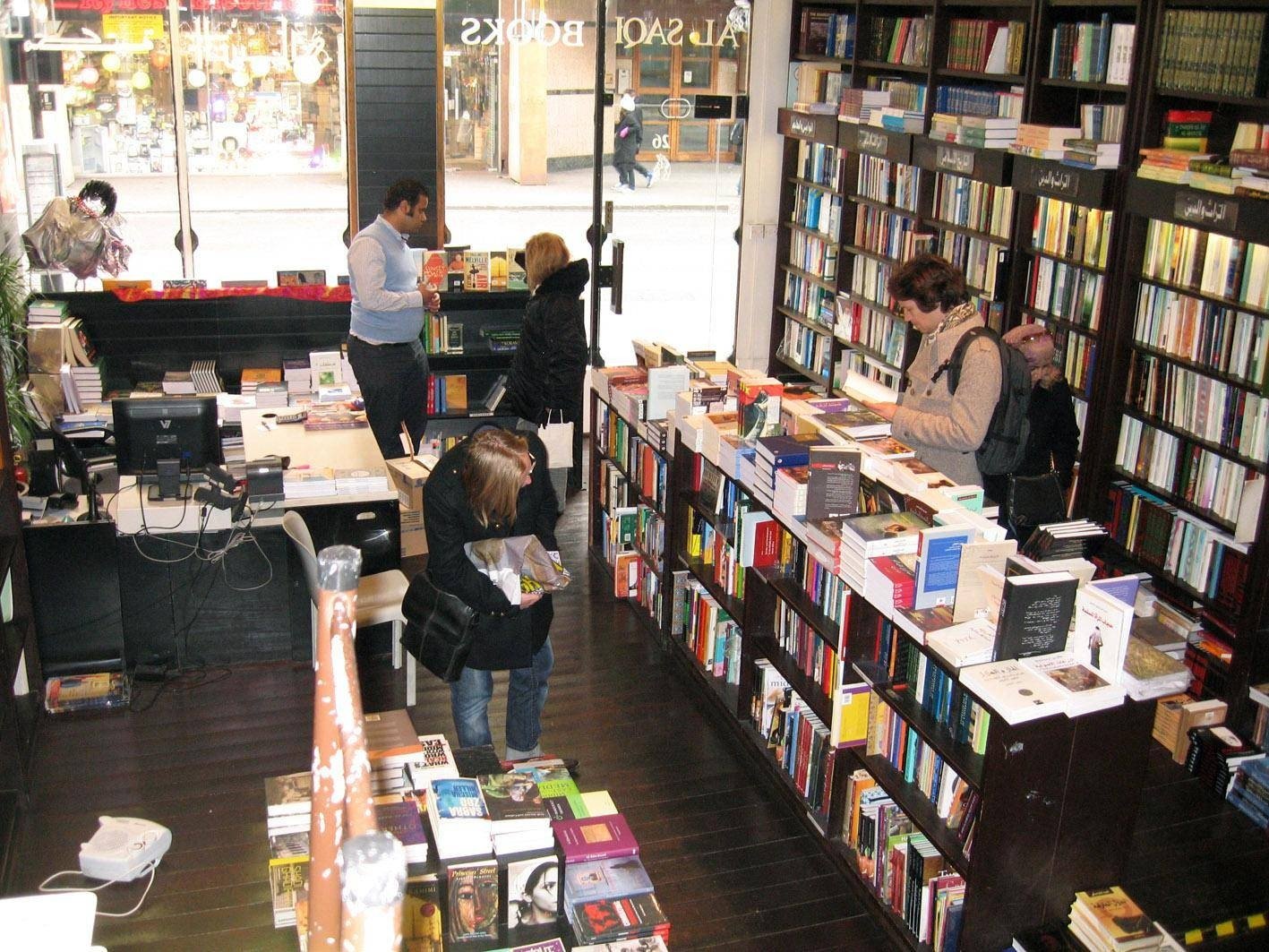

Customers browsing. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Customers browsing. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

“‘The problem,’ I was told, ‘is that Arabic is a controversial language.’ What, exactly, the publisher meant is still a little vague to me — but that Arabs and their language were somehow not respectable, and consequently dangerous, louche, unapproachable, was perfectly evident to me then and, alas, now.”

Further on, Said writes that the unavailability of Arabic literature in translation is no longer an excuse to hold such orientalist views as “small but conscientious publishing houses like Al-Saqi” (among a handful of others) have assembled a “diverse cross-section of contemporary work from the Arab world that is still overlooked or deliberately ignored by editors and book reviewers.”

He specifically mentions Al-Saqi’s publication in English of the Syrian poet Adonis’ “intellectually stimulating” An Introduction to Arab Poetics, translated by Catherine Cobham. Said describes the book as “an uncompromising challenge to the status quo that is held in place by official Arab culture” and “as important a cultural manifesto as any written today, which is what makes the silence that has greeted the work so stupefying.” Adonis himself would often frequent Saqi, Salwa says.

Intergenerational memories

When Saqi announced on Dec. 5 that it would forever close its doors on the last day of the year, it was met with shock and sadness. On social media, people from an array of nationalities in all corners of the world expressed their disappointment at the bookstore closing. Some of them shared anecdotes about what the shop had meant to them. To them, the bookstore was more than just a shop.

Saqi Books. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Saqi Books. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

“Saqi has meant a lot to my family over the years and I’m so sad to see it go,” British-Iraqi Dina, who currently lives in Germany, tells me. She was particularly sad to find out about Saqi closing as she had recently visited London and hadn’t found time to visit the shop, once part of her routine.

“Back when my Iraqi mother first moved to Germany to live with my dad, with limited German and English useless in her surroundings, my dad used to order her books from Al Saqi to be shipped to Leipzig,” Dina recalls fondly. “It’s always had a place in my family’s memory as a way for my parents to stay connected with their home and language when they lived in a very isolated, post-but-not-really GDR city.”

“When I was accepted to study Arabic literature at university, my dad excitedly asked me to send him my reading list and immediately forwarded it to the team at Saqi,” Dina adds. “They were the books that accompanied me throughout my time at uni! And when I was writing my bachelor's thesis on Iraqi literature and was struggling to get in contact with the author I was writing on, it was through Al Saqi that I was put in touch with him.”

In the building right next to Saqi, the famed Iraqi architect Mohamed Makiya established the Kufa Gallery, which became a center for Arab culture in London, hosting art exhibitions and book launches. Makiya sold the gallery to Saqi in 2006 but it later closed down. Makiya’s son, Iraqi-American academic Kanan Makiya, was a good friend and what Salwa describes as a “sleeping partner” of the bookshop.

Salwa and daughter Lynn Gaspard, reopening after the 2021 lockdown. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Salwa and daughter Lynn Gaspard, reopening after the 2021 lockdown. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

In many ways, the gallery came to be an extension of Saqi, as it provided a place to hold book launches and cultural gatherings, Nadim Shehadi, executive director of the Lebanese American University's New York Headquarters and Academic Center, tells me. He used to frequent Saqi regularly when was director of Lebanese Studies at St Antony's College at Oxford University from 1986 to 2005 and has “plenty of anecdotes” to share.

He specifically recalls a close group of what he describes as “comrades,” many of whom were Trotskyist-leftists from Lebanon and other Arab countries, who would come together and have heated discussions about politics. “It’s the stuff of epic, almost Greek-style, tragedies related to everything that happened in the Middle East over a period of 25 to 30 years.”

Salwa says that she wouldn’t call herself a Trotskyist per se, unlike André and Mai, but says she was definitely a leftist “like so many young people in Lebanon at the time. We were influenced by all that was happening in the world. In California, everyone was protesting against the Vietnam War. And in France, the students were against the establishment.” She added that, back then, before the war broke out, and even in the few years after, there was still hope in Lebanon.

The Saqi Books storefront. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

The Saqi Books storefront. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

“As young people, things were a bit easier at the time. We were very hopeful. It’s not like now everything is dark and closed. It’s so difficult to think of or do anything positive now,” she says. “Back then, we didn't think that the war would last for so long.” She even went back to live in Beirut with André in 1983. “We stayed for two years because we thought that the war was over. Imagine! It was just before the mountain war. So then we came back to London, for our children’s sake.”

It’s hard for her to pick one or even a few highlights from a period of 44 years, Salwa says. “It’s very difficult to choose because it’s an ensemble of nice things. The nice people we met, nice authors, nice customers.” She does recall when one particular moment made her realize the important role the bookshop played, not only to the Arab community but also to the “Western” one.

“When Bush and Blair invaded Iraq, we had a very important magazine called Time Out, which came to the shop and took a picture of all the books we were displaying, because they thought that it was an Arab point of view of the world, which was completely against the war and for peace in the Middle East, Salwa says. “And they were not only books by Arab writers; [there were] Western writers too. I mean, many people were against the war. So our display in that magazine attracted a lot of people who didn’t know where to find these books. They were very happy to find a place where they could find different ideas.”

Mai Ghoussoub with Hanan al-Shaykh. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

Mai Ghoussoub with Hanan al-Shaykh. (Courtesy of: Saqi Books)

If the bookshop was so important to so many, and even, as the Financial Times wrote in 2008, “an unequivocal force for good,” what was it that ultimately drove Salwa and André to forever close its doors?

“After Brexit, we had it very difficult in the UK. And then came the economic crash in Lebanon. Everything became very expensive in Lebanon, buying the Arabic books and shipping them to London has become almost impossible,” Salwa says. “And because we couldn’t increase the price, we couldn’t make any profit. It was so expensive that we knew that someone in London would not be able to afford this book. Also, everything in London became more expensive, energy, everything.”

But, with so many loyal customers from all over the world, accomplished writers such as those who would browse through the books and come to cultural events and other famous people dropping by (Salwa says Brian Eno walked in more than once, and Coldplay frontman Chris Martin once bought his children a copy of A Thousand and One Nights) — wasn’t there anyone who tried to save Saqi?

Salwa sighs.

“We would have loved for somebody to help us. But we didn’t want any restrictions linked to this. We didn’t want someone to tell us ‘you can’t sell this book.’ It’s impossible for us … the bookshop was so successful because it was free and independent” — the words of a true revolutionary.