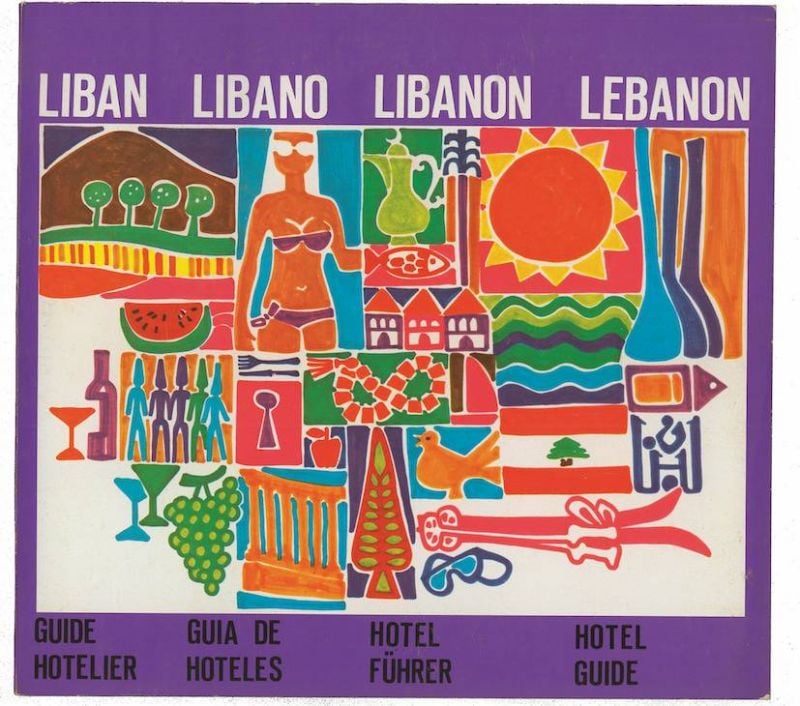

Lebanon, Hotel Guide, booklet, designed and illustrated by Mouna Bassili Sehnaoui, for the National Council for Tourism in Lebanon, 1969. (Courtesy Zeina Maasri).

BEIRUT — Zeina Maasri sits with her leg propped up on a chair. She sprained her ankle while walking around the city. Incurring such minor injuries has become a popular pastime in Beirut, thanks to underlit streets, dotted with potholes and random cement blocks.

The injury keeps Maasri from her favorite pastime — running along the seaside corniche in the morning. Wrenching aside, she’s still happy to be back.

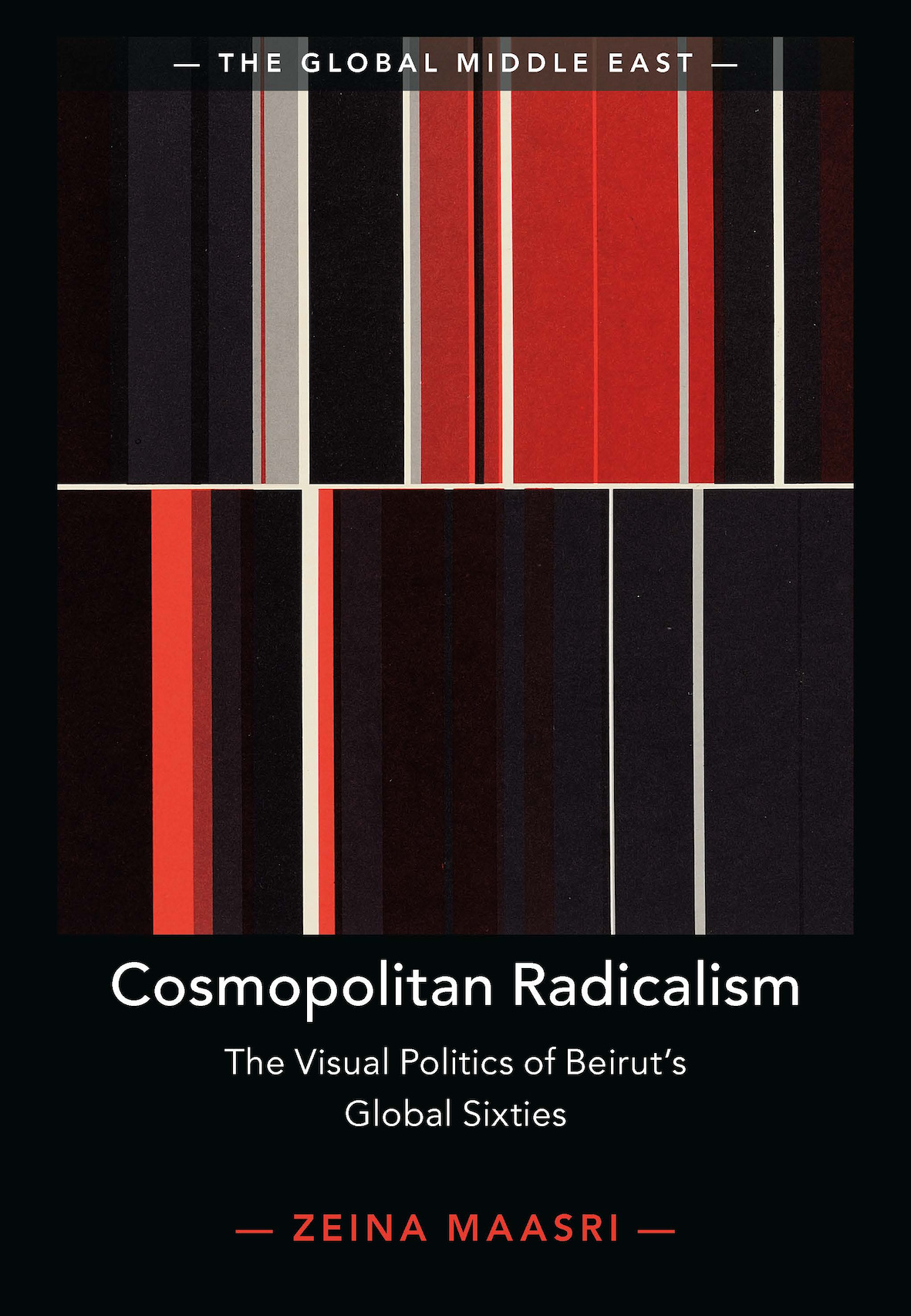

She was back in town recently to present “Decolonizing Modernism: Arab anti-colonial politics in graphic design,” a talk at the American University of Beirut, her alma mater, organized by the Department of Architecture and Design (ArD) and Beirut Urban Lab.These days a senior lecturer in art history at the University of Bristol, Maasri sat down with L’Orient Today to discuss her latest award-winning book, Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties, the curse of Lebanon’s top-down “collective amnesia” and how studying everyday life during revolutions, war, and otherwise “anxious times” is a more compelling way of looking at history — compared to being led by official state narratives, say.

In a country where tribal differences block consensus on an agreed-upon history book, what role can visual culture play in understanding local history? That’s the question that Maasri explores in her books, exhibitions and research.

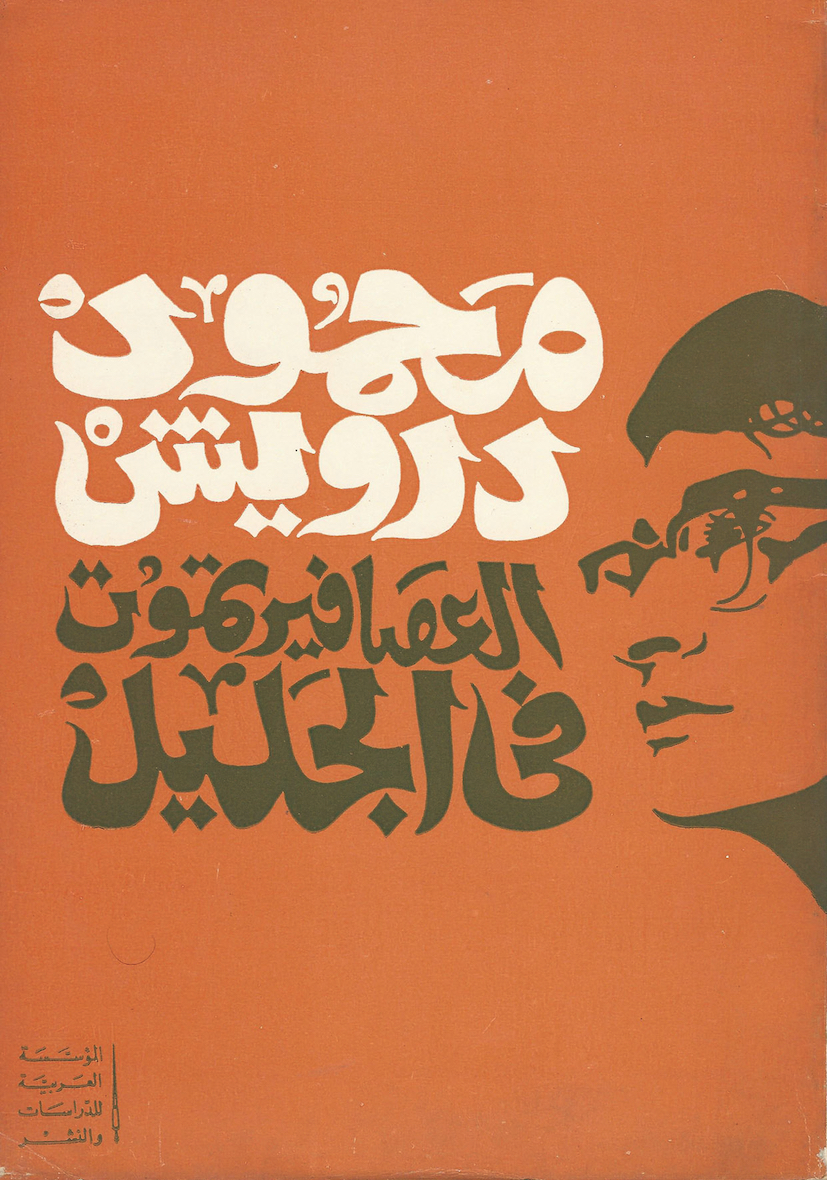

Helmi el-Touni's book cover for Mahmoud Darwish's 'Habibati Tanhad min Nawmiha' (My Lover Awakes from her Sleep) the Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, Beirut 1973. (Courtesy A. Bou Jawde)

Helmi el-Touni's book cover for Mahmoud Darwish's 'Habibati Tanhad min Nawmiha' (My Lover Awakes from her Sleep) the Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, Beirut 1973. (Courtesy A. Bou Jawde)

Collective Amnesia

Maasri’s first book Off The Wall, a discussion of political posters from Lebanon’s Civil War, was released in 2009 in conjunction with the launch of her physical exhibition and exhaustive online resource “Signs of Conflict – Political Posters of Lebanon’s Civil War (1975-1990).” Ongoing since 2003, that project collects, archives and studies the political posters produced by the Civil War’s various warring factions, parties and movements.

One of the functions of this project is to combat “a national endeavor to [erase] all traces of the war, or at least to remain indifferent to it,” says Maasri. It is among a few efforts to reclaim and interrogate Lebanon's “war-laden memories” in a country with, as it is described on Maasri’s website, “a violent past that has been officially buried by the politics of collective amnesia.”

She adds that “the political posters, the book, [and] the exhibition are about the history of the war. Through these images we see the inter-woven ideas and visual landscapes, signs and symbols that reflect the different ideologies or political differences that were part of our everyday [lives]. The point is that we have a lot of war histories that tell us about sectarian violence — which leaders took what decisions that led to war — but we don't have enough about the [everyday life] of war, what its cultural manifestations were.”

“One way to do that was to think of the poster as a historical document but also as a visual document, to think about how war was fought, visually and symbolically, and how these posters occupied walls and marked the territories and are part of the everyday [life] of a war. So it's also the cultural dimension of war, how images construct political identities and shape the imagination.”

Lebanon's Civil War was a tangle of socio-economic and sectarian struggles, ensnarled with regional politics — a knot expressed in the political discourses of the numerous warring factions. That, Maasri writes, “materialized in the production of an equally complex plethora of political posters, with diverse iconography and conflicting significations, as well as distinct aesthetic practices.”

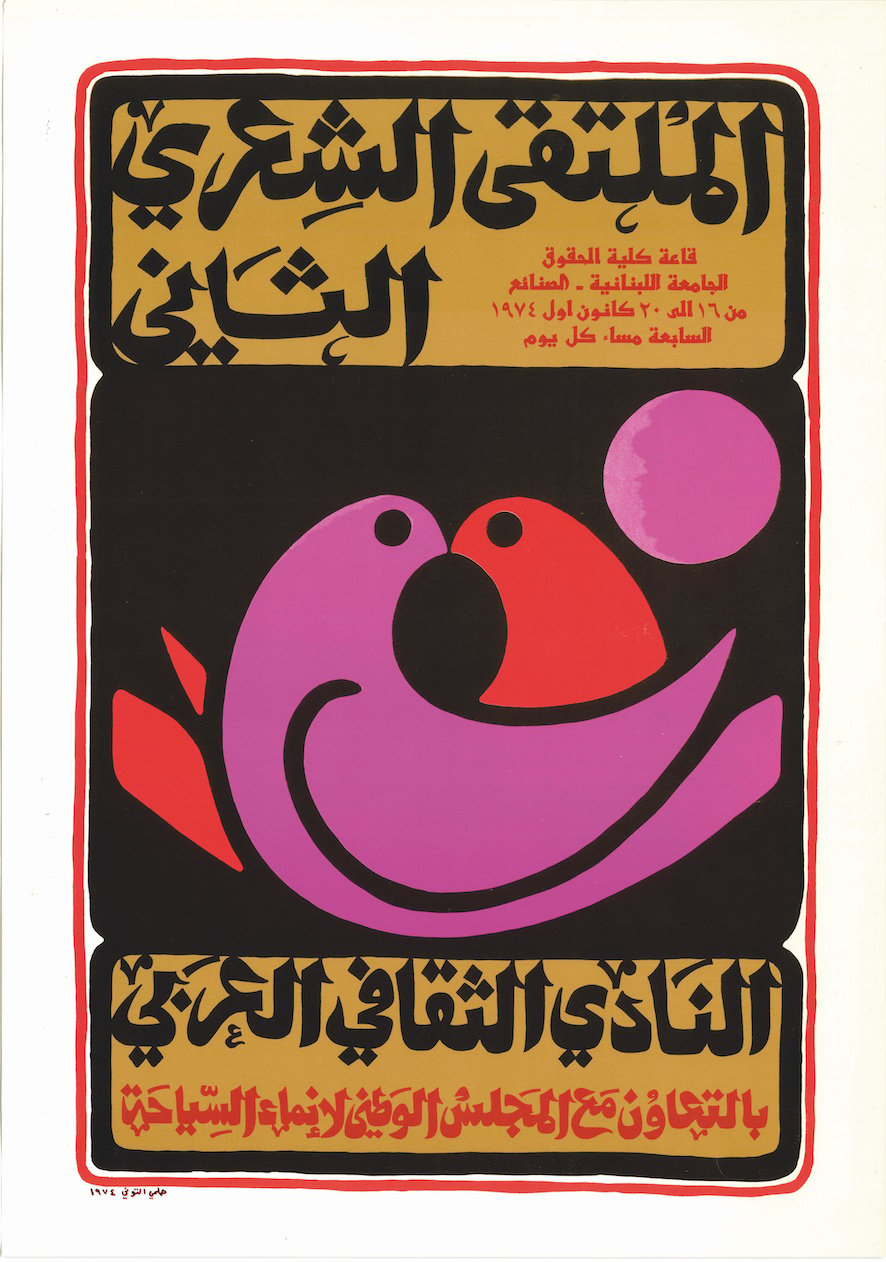

Helmi el-Touni's poster for 'The second Arabic Poetry Encounter,' The Arab Cultural Club 1974, (Courtesy A. Bou Jawde).

Helmi el-Touni's poster for 'The second Arabic Poetry Encounter,' The Arab Cultural Club 1974, (Courtesy A. Bou Jawde).

Beirut’s Neglected history of Internationalism

While working on Off the Wall, she came across a plethora of visual materials that didn’t fit the book’s framework, prompting her to start thinking about a new book that eventually became “Cosmopolitan Radicalism,” published just after the August 2020 port blast.

Derived mainly from the visual culture produced in Lebanon during what Maasri calls the “long sixties” [between 1958 and 1975], the book charts the creative collaborations among different Arab intellectuals, artists and revolutionaries who crossed paths in Beirut. It prompted Maasri to study the historical conditions that preceded the war.

During it “golden age” of haute-bourgeois indulgence, Beirut was also a transnational hub of politically engaged artistic and intellectual production, focusing on anti-imperialist movements and the Palestinian revolution. Maasri found the largely untapped archives of visual culture left by these international networks.

Cosmopolitan Radicalism focusses on a period in between two revolutionary moments, which turned into civil wars, 1958 and 1975. The latter is a culmination of revolutionary processes since 1969. That's totally forgotten by many.”

The enormous archive she amassed was a chance to shed a historical light on this ignored era. “My research into these images also revealed a history of political contestation [for] Lebanon’s political system, [some of whose players wanted] to be part of a global moment of radical change.”

Most importantly, Maasri says, her book goes beyond the reading of sectarian violence to understand Lebanon’s history of protracted political struggle and global conflicts. “The visuals allow us to investigate intimately textured accounts of local agency and resistance,” Maasri says, “rather than geopolitical interventions and imperialist machinations.”

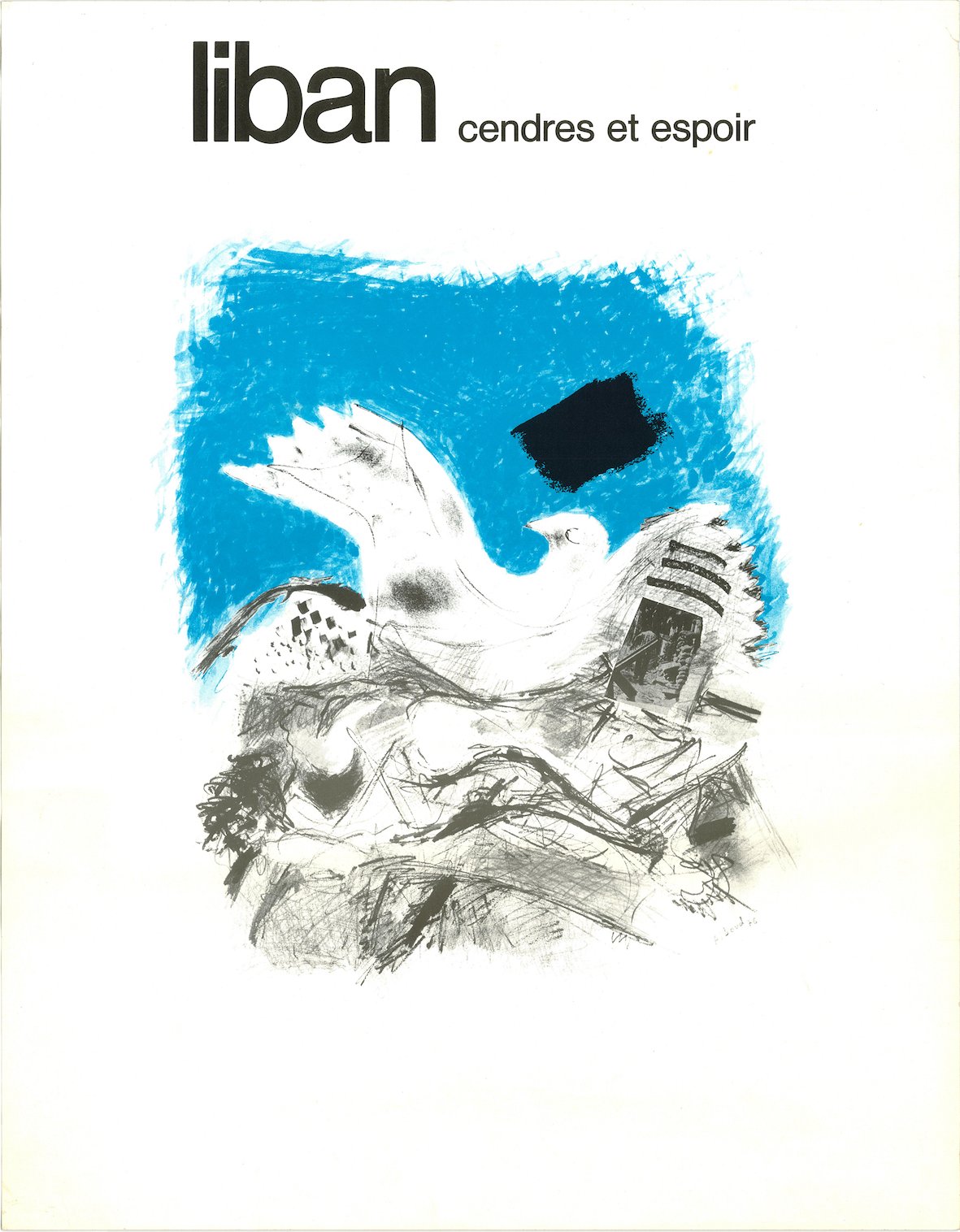

Chafic Abboud's poster: 'Lebanon: Ashes and Hope.' (Source: http://www.signsofconflict.com)

Chafic Abboud's poster: 'Lebanon: Ashes and Hope.' (Source: http://www.signsofconflict.com)

Defying ‘Winners History’

As the unattributed but oft-quoted saying goes, “the victor writes history.” Maasri believes in the power of ephemera, which includes visual culture.

“It's something that is not meant, or made, to last,” Maasri says. “It's not something to keep in the archive, like government documents and treaties, but at the same time, it's important because revolutionary moments are the voice of the people who are on the street.

“Rather than the documents of those who make the treaties, who get to become the statesmen, who get to determine facts and decisions and diplomacy — which are the documents that are usually preserved archivally — the ephemera is the voice of everyday people in revolutions. They trace the transformations that are happening day by day, your sense of politics changes while you're in the streets and and you're perpetually imagining your relationship to other people, as you participate in such momentous uprisings and street marches,” she adds. “Those fleeting moments are so crucial if we were to write a people’s history of revolutionary transformation.

“Unfortunately, archival ephemera [posters, leaflets, flyers, cards, graffiti] is usually not deemed as important as official state documents, but I believe it has its place in the archive. The ephemeral is something that is the fleeting momentary emotional transformations which are so crucial to the dreaming of an alternative future.”

Unruly documents?

Maasri believes that, if approached with nuance, visual culture can play a role in understanding the intricacies of history. While she welcomes the wealth of visual culture shared on platforms like Instagram, she cautions against the flattening of images for want of historical context.

“Visual culture does give access to the past, but it needs to be narrated. On Instagram, I think there’s a risk that the image alone is consumed as a nostalgic fetish. It needs to be part of the historical framework you have access to,” Maasri says. “It’s a material artifact, visual evidence, of a particular moment.”

During an exhibition of Civil War-era political posters, Maasri says one of her graphic design students said something that stuck with her. “‘Posters don't lie,’ she said, which is interesting, because when you think of a poster now, it is all about rhetoric. What the student meant is that the poster as a historical document does not lie. Whereas politicians, they lie about their violent past as warlords, because they've remained in power.”

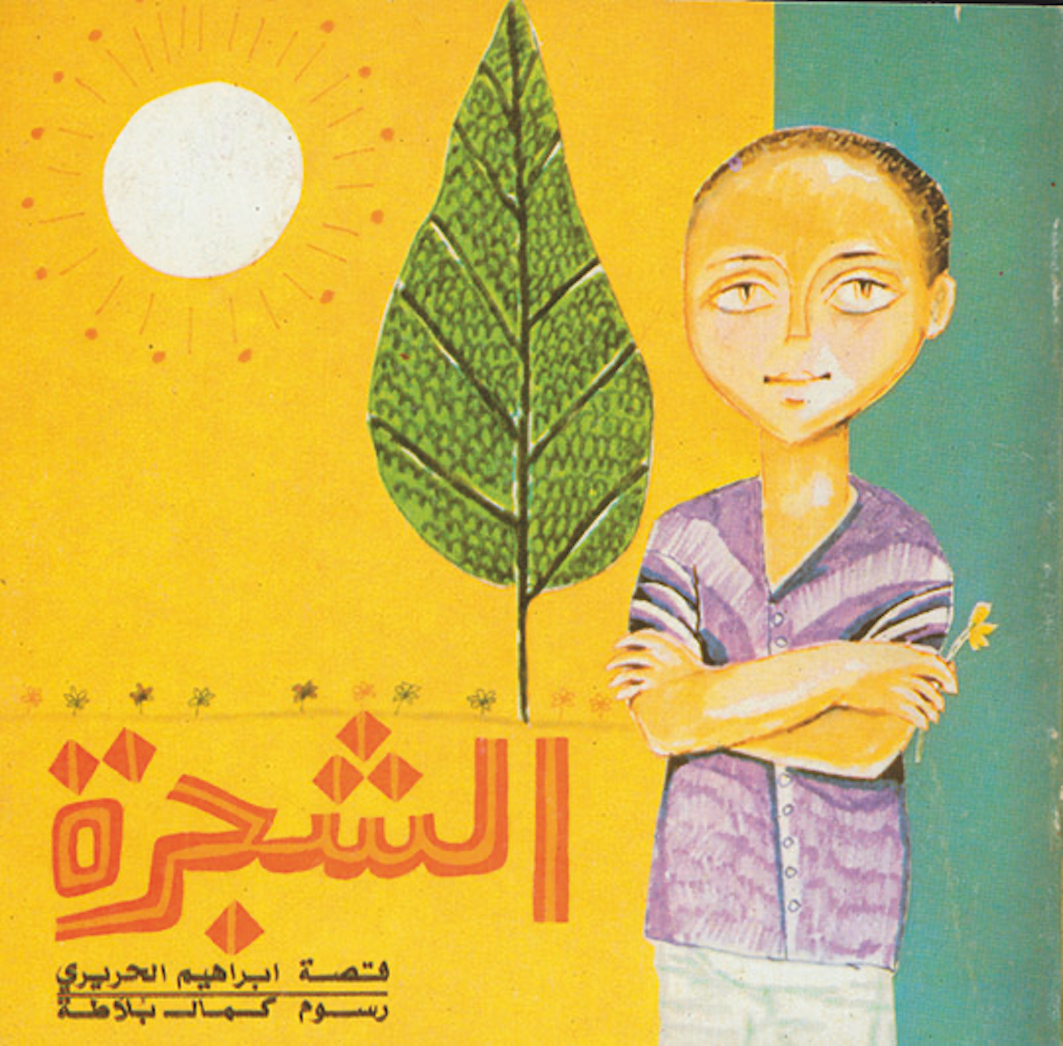

Kamal Boullata's illustrations for al-Shagara (The Tree), a children’s book published by Dar al- Fata al-Arabi, Beirut 1975. (Courtesy Zeina Maasri).

Kamal Boullata's illustrations for al-Shagara (The Tree), a children’s book published by Dar al- Fata al-Arabi, Beirut 1975. (Courtesy Zeina Maasri).

“It’s difficult to imagine a future here.”

Maasri was born and raised in Lebanon and she worked as a lecturer at the AUB for 13 years. This has been her first extended visit since leaving to do a Ph.D in Art History and Design in the UK 10 years ago.

“I know it’s because I don’t live here anymore, and I don’t have to deal with the same daily struggles," she says. “I'm not exactly a tourist. I don't necessarily get annoyed as I used to by the daily obstacles of life here, but I can see how difficult it is to imagine a future here.”

Maasri developed an interest in the history of the region’s visual culture while teaching graphic design at the AUB, which led her to pursue a Ph.D in exactly that subject.

Her various projects suggest that Lebanon is always in the back of Maasri’s mind. She says her fascination for the country’s past goes beyond the personal and the academic.

Cosmopolitan Radicalism came out in August 2020, what Maasri calls “a difficult time.” It was just after the horrific port explosion killed not only hundreds of people but also when little was left of the revolutionary spirit that had swept the nation almost a year earlier – what lessons can the book teach us about the uprisings of October 2019 and how did Maasri witness that time period from abroad?

“I wasn't physically here,” Maasri says. “That's why Twitter is so important, to just try to connect as much as possible with what’s happening on the ground and with friends. It was a very bizarre, difficult time. As if I lived in two worlds, just pretending that everything is normal, go to my classroom, in the UK while your heart is somewhere else basically,” she adds.

Archiving the thawra?

Maasri says she doesn’t feel “the urge” to archive the 2019-20 thawra. “I felt a greater urge to really understand what the new generation is like,” she says. “Some of the people involved were my former students. I was interested in how a new generation of artists and designers were exploring their own skills and using new tools, but also how they came to be very politically active at the forefront of many things. That's how I was looking at images in that way, in addition to the politics.”

She did hear about people attempting to archive the events of 2019-20 but she wasn’t going to be involved unless someone asked her, and not only because she’s living overseas.

“I'm used to writing through the lens of history,” she says. “This has been the case for me since 2010, with all the uprisings that have been taking place in the Arab World — I'm either an observer or or someone who's actually on the streets. Always involved in many different activities, but not as a researcher.

“I research the past but I’m not very comfortable just being the detached observer of the present. I think I'm more comfortable with the critical distance that one takes over events in the past. I think I live the present as someone who is emotionally involved, but I think that's also why it doesn't occur to me that I need to do something about current events academically. I think I just get engaged, even if I’m far away, geographically.”

'Beirut is ours to keep'

While she’s still in Beirut, Maasri will be presenting a paperback edition of Cosmopolitan Radicalism at Hamra’s Barzakh cafe on Dec. 13. She has a long-time collaboration with Abboudi Bou Jawde, beloved Hamra movie-poster archivist and founder of AlFurat Publishing & Distribution, which unfortunately had to close down three years ago due to the financial crisis. Maasri and Bou Jawde are currently working on an exhibition and online platform focussing on the wealth of visual culture in the Arabic book publishing industry. One of the reasons she’s in town is to dig through “thousands” of archives to prepare for yet another dive into Beirut’s forgotten past.

It seems that, no matter how much Beirut — or rather those who are hellbent on torpedoing it into the ground — disappoints, its citizens refuse to give up on her, whether they are still physically present in the city, or treasuring her from afar.

As Maasri wrote in the dedication of her Ph.D thesis, “Beirut is ours to keep despite its failing promises.”

(Courtesy Zeina Maasri)

(Courtesy Zeina Maasri)