Unveiling of the proposed new administrative and residential towns in the suburbs of Beirut. Map of Beirut rotated 90 degrees to the right showing the administrative city of Bir Hassan “Nouvelle Ville De Bir Hassan.” (© OLJ Archives)

BEIRUT — Though president of Lebanon for just six years, Fouad Chehab continues to be revered to this day. His lasting legacy will always be tied to the creation of state institutions such as the National Social Security Fund and the Central Inspection Bureau. He is also less fondly remembered for more draconian policies, such as the extensive use of a special police force known as the deuxième bureau. But his efforts on the urban front are often overlooked, yet they are essential in understanding how Beirut is shaped today.

An urban plan for Beirut and its suburbs

When Chehab entered office in 1958, he inherited a country that was deeply divided both politically and socially. It was still reeling from the civil strife that tore Lebanon apart between July and October of that year.

Beirut witnessed much of that fighting, which aggravated many of the urban issues from which the city was already suffering. Since World War II, Beirut had grown dramatically. According to the IRFED, a French Institute for research, education and development, survey of 1959, Lebanon’s population more than doubled to 1.626 million people between 1932 and 1959, with 27.7 percent concentrated in Beirut alone.

The city was faced with heavy migration flows from rural areas, which, coupled with housing shortages, led to overcrowded neighborhoods as well as informal settlements (e.g. Karantina and Ouzai) with a population of 50,000 inside and outside of Beirut.

Traffic was becoming a problem, and the urban strife effectively created sectarian flashpoints, such as Basta and Monot.

To fix this, Chehab enlisted the help of French architect Michel Ecochard, who had worked in Lebanon on and off for 20 years on projects in Beirut, Saida and Jounieh, as well as in Arab countries such as Morocco, Syria and Kuwait.

Ecochard wrote in a letter to the president: “President, I have a plan, I know what you have to do for Lebanon.” This letter was found by Eric Verdeil, professor of urban geography at Sciences Po, Paris, while doing his doctoral research. Verdeil says Chehab effectively gave Ecochard complete creative control over the planning of Beirut.

Having gained a keen familiarity with the urban issues affecting Beirut through his previous projects in Lebanon (such as Plan Danger, Beirut’s first master plan designed in 1933), Ecochard tried to fix them through a functionalist modernist approach, as championed by French-Swiss architect and urbanist Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier.

The movement espoused a top-down approach to city planning, valuing order and space over dense and overcrowded neighborhoods. Instead of shaping streets around buildings, the approach prioritized wide roads that would then shape the buildings along them.

Ecochard produced a sweeping master plan of Beirut and its suburbs. According to Verdiel, it envisioned the construction of five towns in the surroundings of Beirut: two to house government offices and three dedicated to residential use. Beirut would be connected to these five towns by a highway system that would start in the heart of the city and stretch out to the suburbs.

The point of the plan was to deflate the dense areas of Beirut and regulate the growth and land use in the city. It set densities over certain areas, placed industrial sectors outside the city and added protections to the coastline, beaches and green areas.

An ambitious plan for Downtown Beirut

The master plan Ecochard prepared had several components. Some of these were outlined in more detail by Lebanese architects Assem Salam and Pierre el Khoury. The most ambitious was in Downtown Beirut in the overcrowded inner city areas, specifically the neighborhoods of Saifi and Ghalghoul. These were two of the oldest neighborhoods at the time, having not seen any new development or construction in 50 years.

Nicknamed the Manhattan of Beirut, the plan sought to create a new business and financial district that would rival Hamra street and envisioned skyscrapers 100 meters high placed in between large open spaces, mirroring that of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for the city of Paris.

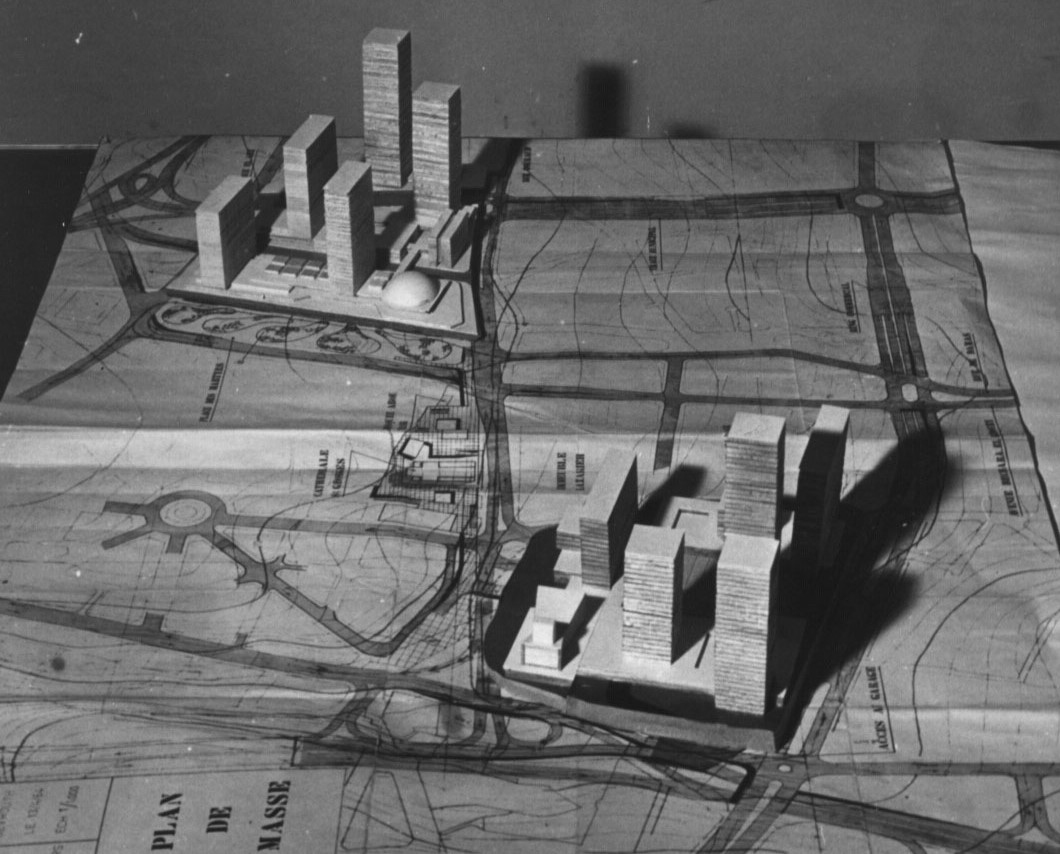

Models of the two proposed business districts in Downtown Beirut laid over a road map, 1965. (© OLJ Archives)

Models of the two proposed business districts in Downtown Beirut laid over a road map, 1965. (© OLJ Archives)

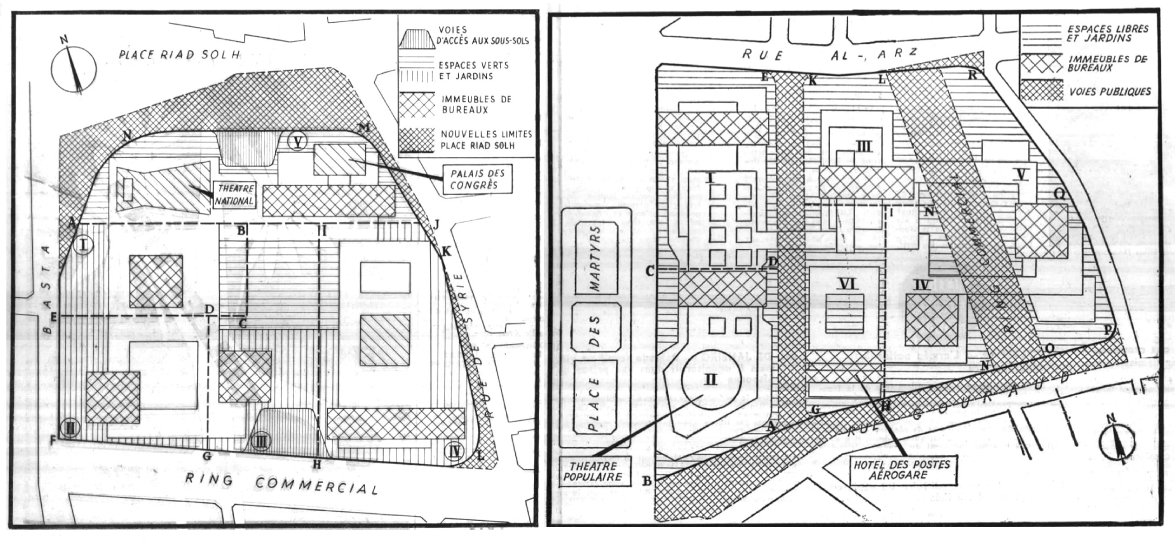

Plans published at the time in L’Orient show highrises of 33 floors in both neighborhoods. As designed by architect Jacques Marmey, these were to be surrounded by gardens and open spaces. Like all modernist plans, the car was placed at the center of this vision: aside from underground parking with a capacity of 4,000-7,000 vehicles and 200 buses, the districts would be connected by wide vehicular arteries, Salim Salam for Ghalghoul and a double lane boulevard set to stretch from Saifi to St. Joseph University on Huvelin street, the modern foundations of George Haddad street that divides Saifi Village from Gemmzaye.

Saifi would harbor a dome-shaped theater while Ghalghoul would host a convention center and a stock exchange. The plan also provided for the widening of Riad al-Solh Square in the case of the former and Gouraud Street in the latter. But the traffic in the new districts would be pedestrian only.

Roger Geahchan, deputy editor-in-chief of L'Orient, described the plan in glowing terms: “These two quarters of the traditional center of Beirut will be transformed from top to bottom and developed in the image of a modern capital in full expansion.”

Plans for the proposed business districts of Ghalghoul (left) and Saifi (right) (© OLJ Archives)

Plans for the proposed business districts of Ghalghoul (left) and Saifi (right) (© OLJ Archives)

A moral overtone

Much of the implementation was to be done through urban renewal, meaning that people would be uprooted, their homes and neighborhoods destroyed and then rebuilt from scratch.

Although the main purpose of the master plan was organizing the city, it also had moral overtones, according to Verdeil: “These areas were considered slums, the red quarter or so. There was a moralistic disdain for these areas, and so they needed to be cleared.”

The moralizing aspects were the brainchild of sociologist Samir Khalaf, who L’Orient reported at the time had “drawn up a study on the problem of sex work [in the neighborhoods] and the rehousing of brothel occupants.” This was used to justify a moral crusade. Khalaf had just published a book about sex work in Lebanon called Prostitution in a Changing Society (1965). L’Orient chimed in on the subject, running the headline: “In 10 years, the leprous buildings in the city center will have disappeared.”

Such moral disdain points to a larger critique of state-led urban planning and development under Chehab’s presidency, says Jan Altaner, a PhD candidate in history at the University of Cambridge who researched the history of the Ghalghoul neighborhood. “The poorer communities inhabiting Saifi and Ghalghoul had no place in the grand, modernist schemes to transform Beirut’s center. The urban renewal plans simply implied their displacement, as part of an effort to push poorer populations out of the city center.”

In the end, most of the Beirut master plan was not implemented. There was strong opposition to the plans for the suburbs from political and economic elites who refused controlled expansion into the suburbs via the new towns, because they wanted to use the land as they saw fit, without adhering to the building limits imposed by the plan, as reported by L’Orient in 1966.

As for the business district downtown, Verdeil says the 1967 Six-Day War between Israel and the Arab states of Egypt, Syria and Jordan rendered the endeavor financially non-viable: “The plans had been approved, but there was no money to start the plan.” The project also faced resistance from the residents. “They did not want to be expropriated,” Verdeil added.

A continuing controversial legacy

Although long out of office and long since dead, Chehab’s policies continue to trail us into the present, as Ecochard’s 1963 master plan set the tone for subsequent development projects.

The first of these emerged during a short lull in Civil War fighting in 1977, with a plan to rebuild downtown Beirut that was largely based on Ecochard’s master plan. Reformulations of this followed in the 1980s-90s leading all the way up to Solidere, the Lebanese joint-stock company in charge of planning and redeveloping Beirut Central District following the conclusion, in 1990, of the Lebanese Civil War.

Indeed, it was the 1962 town planning law that allowed real estate companies such as Solidere to spearhead a redevelopment plan of entire neighborhoods, with the government’s approval.

Another aspect of the master plan which would prove to be contentious was the highway project, specifically the one planned inside and around Beirut. Architect Mohamad Tohme says this project has proven to be impractical in the Lebanese context. “Echocard treated Beirut as if it was Paris. The idea of highways between Beirut and other cities was necessary, but the city center for us is the heart of the city. Separating it by highways from the other parts was not a good idea. The size of Paris is different from Beirut.”

Map of business districts embedded in proposed highway scheme. (© OLJ Archives)

Map of business districts embedded in proposed highway scheme. (© OLJ Archives)

The construction of some of the proposed highways stalled during the Civil War, only to resurface in the 1990s and 2000s. The ones that were implemented ended up dividing neighborhoods, such as Karm Zeitoun and Nabbaa, while others faced opposition. Indeed, had activists not mobilized to stop implementation, the Fouad Boutros highway could have destroyed many of the oldest parts of Mar Mikhael and Achrafieh.

Overall, Chehab’s term in relation to urban policies “opened the way for a new thinking about Beirut, which was more modern,” says Verdeil. “And this, in a way, was catastrophically implemented after the Civil War. So there is a kind of continuity between Chehab and after.”

But he adds that this should not necessarily overshadow his achievements on regional issues: “What he did, to try to balance a little bit more the investments at the scale of the country in the rural areas, was certainly something that was a very strong legacy.”