The Baabda presidential palace during a COVID-19 disinfection campaign.

Since the presidential election period began, the concept of a “candidate who would draw a consensus,” also referred to by some as a “compromise candidate,” sounds like a mantra.

Since there is no clear political majority in Parliament, the various parties and other actors appear to understand that there must be a middle ground.

With the exception of a few political parties, including the Lebanese Forces who have clearly stated that they favor an anti-Hezbollah candidate, the majority of the other parties have pinned their hopes on a candidate who can win the endorsement of the majority of Parliament, if not all the political actors. In short, it is about a figure who does not have a very political bent in one way or another.

Western powers, which have long played a decisive role in Lebanon’s presidential elections, seem to be on the same page. However, if everyone, or almost everyone, already consents to the concept of a “compromise candidate,” why is it so difficult for the Parliament to agree on the future president?

“The agreement has not yet matured. It is simmering gently and slowly,” many politicians have come to say on the airwaves in recent weeks as the election deadline nears. This is because while everyone seems to agree on the concept, each person has their own definition of what a compromise president actually is.

Hence the difficulty of finding the rare figure who can meet all the criteria, as defined by a plethora of political actors with widely varying orientations.

Several prospective candidates are trying to introduce themselves as “consensus figures,” albeit through acts of contortion. This is the case of the Marada Movement leader Sleiman Frangieh, seen as an ally of Hezbollah and Syria, who has tried to ride the wave of a consensus candidate as he continues to express being part of the March 8 camp.

His competitor from Zgharta, MP Michel Moawad, is perceived as being part of a camp as well. Claiming to be part of the “sovereignist” camp that opposes Hezbollah’s arsenal, the MP is also trying to play with the semantics. According to him, there is a “genuine and a fake consensus.” A genuine consensus, he argued two weeks ago on journalist Marcel Ghanem’s TV talk show, would constitute “an agreement on the concept of the state, not a compromise on Hezbollah’s weapons.”

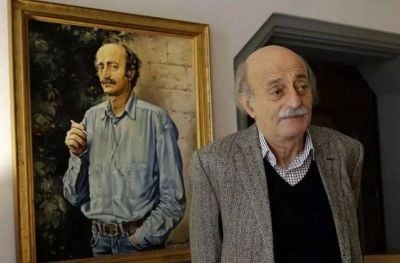

Everyone is playing with words. Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) leader Walid Joumblatt was among the first to grasp that only a compromise could lead to the election of a president in the current political climate. By opening a dialogue with Hezbollah in early August, he forced all the other actors to reposition in the center.

However, Joumblatt also has his own definition of a consensus candidate. For him, it is a “technocratic figure that has a political background without necessarily coming from any political party,” he told L'Orient-Le Jour in a recent interview.

The PSP leader also expressed his opposition to electing a candidate who would be perceived as hostile to Hezbollah, as it would raise “contentious issues, including the implementation of [UN Resolution No.] 1559,” which calls for the disarmament of all militias in Lebanon, as well as for government control of all Lebanese territory.

‘Not the strong president’

The twists and turns of semantics do not end there. Dar al-Fatwa, the country’s top Sunni religious authority, has also invoked the need to agree on a consensus president.

But for the Sunni institution, the most important thing is that the new president respects the Taif Agreement, which gives the prime minister — traditionally a Sunni Muslim — a main role to assume in the executive branch.

The institution’s call is echoed by Saudi Arabia, which is also encouraged, alongside the United States and France, for the election of a “president who can unite the Lebanese people,” the three countries said in a statement last month on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York.

Bkirki, the seat of the Maronite church, also has its red lines. The institution wants to see a candidate “who would unify and who does not have personal interests” filling the presidential seat, Maronite patriarch Bechara al-Rai said in a recent sermon.

Rai gave further explanation in another sermon, saying that the church “does not want a president elected as part of an arrangement,” but rather one “who can really lay the foundations of a solution for Lebanon, with international anointing.”

In other words, he implied, the church wants a president who has a say, and who is not a puppet in the hands of Hezbollah.

For the Forces of Change MPs, a consensus president should not be part of the traditional political club. However, this makes the idea of a unifying figure who has no connection to the political establishment perhaps even more difficult.

As for the definition of a “consensus” candidate put forth by the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) leader Gebran Bassil, it is equally peculiar. While he avoided actually using the term “consensus” — which contrasts sharply with the principle of the strong president which the Aounist camp treasures — he has instead spoken of someone with “representativeness,” meaning someone who has a substantive presence in Parliament. According to Bassil’s recent assertions, the quality is a prerequisite for any candidate’s accession to Baabda, and would allow Bassil to force competitors, including Frangieh and army commander Joseph Aoun, out of the race.

“The consensus president is, as defined by the Taif agreement, the one who can epitomize national unity,” Michael Young the editor of Diwan and a senior editor at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, told L’Orient-Le Jour. “It is not the one who is strong within his community at all.”

‘No sign of consensus’

Even Hezbollah has invoked the need to elect a consensus president because it is forced to — given the lack of a majority in Parliament — though it said it prefers a candidate from its own political camp.

“We want a candidate who advocates clear principles on Lebanon’s role with its environment, on the resistance and conflict with the enemy,” Mohammad Afif Naboulsi, a spokesperson for the party, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

So, how can all these definitions be reconciled? Can a compromise emerge in such a polarized context?

Maronite patriarch Rai probably best summed up the impasse in his Sunday homily on Sept. 25: “The idea of an internal consensus on a president is praiseworthy, but the priority is for the democratic mechanism and respect for electoral deadlines ... the wait for a consensus is a double-edged sword, particularly since no sign of this consensus has been seen so far.

In 2016, it had taken more than two years of presidential vacancy and multiple compromises to elect Michel Aoun.

And before that, in 2008, it was the May 7 coup de force, when operatives of Hezbollah and its allies invaded parts of Beirut, and the subsequent Doha agreements that led to the election of Michel Sleiman.

What will break the deadlock this time?

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.