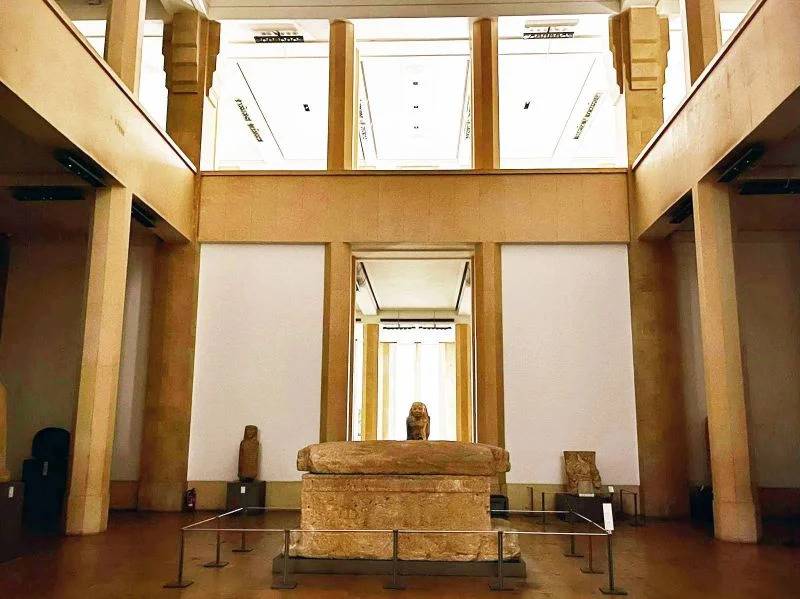

Inside the National Museum of Beirut. (Credit: Nour Braidy/L'Orient-Le Jour)

BEIRUT — At the foot of the columns that adorn the National Museum of Beirut, a black cat basks in the sun. Guards sit on either side of a security gate that is out of order. “There’s no electricity, but you can still come in,” one of the guards says.

The entrance ticket costs LL5,000, worth almost nothing today with the depreciation of the Lebanese lira. The heat inside is stifling, with no air conditioning, no lights and no functional elevator.

The first floor, along with its masterpieces, such as the Phoenician Ahiram sarcophagus, the tribune of the temple of Eshmun and the Byzantine-era Good Shepherd mosaic, is plunged into darkness. Unable to ensure more than four hours of electricity supply per day, it has been six months since the museum opens its doors from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. rather than to 7 p.m. During the month of August, the national museum experienced at least 10 consecutive days of total darkness, according to museum employees.

The power outages, now lasting least 18 hours a day, have consequences on the museum’s pieces. “The fluctuating temperature and relative humidity can be a major factor in the deterioration of artifacts, regardless of their materials,” says Nathalie Hanna, an archaeological conservator.

Museums must “ensure basic requirements to prolong the life of their collections,” and power outages “do the opposite,” Hanna says. Without proper air conditioning, “the objects incur serious degradation that can be irreversible, such as mold, corrosion and deformation of organic materials.” She also notes that “the daily work of managing the works, cleaning and inspecting their condition is more difficult without power.”

Visible mold

Every day, especially in summer, at least 150 people enter the museum, despite the lack of light and air conditioning.

Emilia, a German tourist, tries to read the signs as best she can. “I’m going back to Frankfurt tomorrow and I really wanted to see the museum before I leave,” she says. But when she tries to get to the basement, she comes face-to-face with an imposing black metal door. This floor, where the world’s largest collection of anthropoid sarcophagi is housed, is closed to the public when there is a power outage.

This is also where the so-called “Maronite mummies,” the bodies of several medieval-era villagers discovered in 1989 in Lebanon’s Qadisha Valley, are on display.

To preserve these mummies and their fragile clothes, a dehumidifier must be constantly functional. This is no longer the case due to power cuts. Now, small amounts of mold are visible on the mummies’ clothing. According to Hanna, the clothes will “eventually be at risk without climate conditioning.”

For now, she says, “the situation is manageable, but in the long term, the consequences could be much more serious,” she said.

$500,000 in donations

At the headquarters of the General Directorate of Antiquities (GDA) in Beirut, Sarkis al-Khoury rolls up the sleeves of his white shirt. The GDA building is next to the National Museum and follows the same electricity cutoff schedule. After 2 p.m., Khoury and his teams work without electricity.

“The situation is very difficult,” he said. “Lebanon is completely impacted and we are in the same boat.” Today, his strategy and that of his administration is focused on “preserving the heritage in times of crisis,” he tells L’Orient-Le Jour.

“The GDA relies heavily on donations, especially after the Aug. 4, 2020 [port explosion], … which did not spare the museum,” Khoury says. The donations largely come from the Aliph Foundation, which protects heritage in what the group refers to as “conflict areas,” as well as UNESCO and several foreign embassies, he explains.

It is the latest donation from Aliph that, Khoury hopes, will bring the museum out of obscurity. More than $300,000 has been earmarked for the installation of solar panels. Thanks to this donation, a humidity control system for the display cases and dehumidifiers will also be installed.

While waiting for the installation of solar panels, the foundation has already twice funded twice, since Nov. 2021, fuel for the museum’s generator, costing a total $30,000. “After the explosion of Aug. 4, 2020, Beirut became a priority for us, and we mobilized very quickly,” Valéry Freland, executive director of Aliph, told L’Orient-Le Jour. He adds that more than $140,000 was used to replace windows and doors, repair false ceilings and elevators. The money allowed for dehumidifiers and mobile air conditioners to be installed and the museum’s security system reinforced.

For Freland, “the national museum represents the memory of Lebanon and its history. It is a place of wonder and hope. It is therefore important to preserve it, especially in a city that has suffered from war and an explosion.”

Underpaid and understaffed

Despite the donations, other challenges remain.

When the economic crisis began in 2019, many museum employees decided to emigrate. “To protect heritage in Lebanon, you have to protect the staff who are in charge of it,” says Khoury.

If, before the economic crisis, the monthly salary of archaeologists, architects and other GDA employees was worth more than $2,000 at the official rate of LL1,507 to the dollar, it is now the equivalent to only $100 when calculated at the parallel market rate of LL39,800 per dollar. As for the salary of the guards, it is today worth today only $40, Khoury explains.

Entrance fees to archaeological sites and museums were increased in recent weeks. But will this be reflected in the salaries of civil servants? To enter the national museum, for example, Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian visitors will pay a fee of LL40,000. Visitors from Arab countries will pay LL80,000 and those from other countries will pay LL250,000.

Since the beginning of the crisis, many employees have resigned. Those who remain work only three days a week. And running an administration without cash complicates every little task, such as buying ink or paper.

Faced with this situation, the caretaker Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada says he remains confident. “The situation is sensitive, of course, but we have no fear, either for the cultural sector in Lebanon or for the museum,” he says.

“We have to be inventive, think outside the box to find solutions.” For him, “The most dangerous thing is to think that this country is a hopeless case. Lebanon has a huge potential despite everything. We must continue to resist.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour.