A lab technician works on samples to test for cholera, at a hospital in Syria's northern city of Aleppo on Sept. 11, 2022 (Credit: AFP)

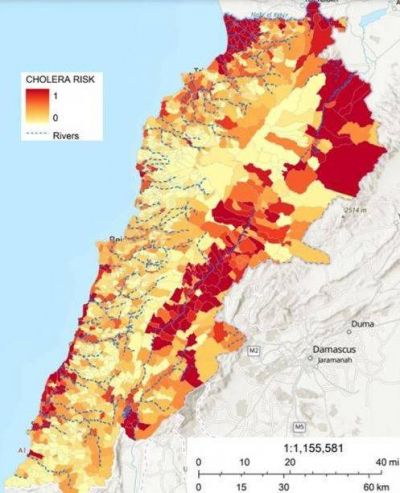

BEIRUT — Lebanon’s first cholera outbreak in nearly three decades has spread in rural areas in the north of the country, raising concerns about the possibility of the disease reaching more people or, at worst, overwhelming the public health system.

There have been 29 confirmed cholera cases and one death, as of the latest Ministry of Public Health data released Thursday. The confirmed cases are so far clustered in the governorates of Akkar and Baalbek-Hermel.

Cholera is spread when the bacterium Vibrio cholerae enters the body, which most often happens because of contamination of food or water with human feces that are carrying the bacteria.

Lebanon’s general household water supply is, however, a lower risk than contaminated fruits and vegetables, according to experts on the country’s water infrastructure, who add that there are safeguards in place that reduce the chances of contamination of the residential water supply.

“The possibility is always there,” says Nadim Farajalla, a professor at AUB who studies Lebanese water infrastructure. But “what I personally am not concerned about is the network itself,” or, in other words, general contamination of water networks that supply millions of people.

Of the four regional water establishments in Lebanon, the Beirut Mount Lebanon Water Establishment (BMLWE) supplies, by far, the largest number of people in the country: almost 2.7 million.

Water in this network is treated with chlorine, Farajalla says, and sometimes also goes through sand filtration at the source before being distributed through pipes.

Gaby Nasr is head of the technical department at the North Lebanon Water Establishment (NLWE), the country’s third largest water network, with more than 560,000 people connected. His jurisdiction is also the epicenter of the current cholera outbreak.

According to him, all of their network’s water sources are equipped with sampling stations to test the water quality, and chlorine and other chemicals are injected at the “heart of the networks” in quantities that meet international standards: 0.25 to 0.35 milligrams per liter.

Currently, authorities have upped the dosage in specific areas of the north to 0.55–1 milligrams per liter as a precaution to ensure the water does not carry pathogens such as cholera, Nasr tells L’Orient Today.

He said they are cooperating with UNICEF and the International Red Cross on the cholera response, while UNICEF is bolstering supplies of chemicals to treat the local water supply.

Electricité du Liban has also provided three days of sustained electrical power to operate the water network. UNICEF may provide some generator diesel in the near future, Nasr added.

In a statement to L’Orient Today, UNICEF said they provided maintenance and repair to 13 chlorination systems in NLWE, as well as two main generators, and replenished NLWE’s chlorine stock. Nationwide, they prepared 30 tons of chlorine to be dispatched to different water establishments based on their evolving needs.

“Risk exists everywhere,” Nasr said. “The risk factor is there. If they don’t give us electricity from EDL, and no one is able to help us with diesel — because we as an institution have reached a financial situation where we are not able to acquire it — of course, there is a risk.”

Still, to date, sampling has not revealed any contamination in the network, Nasr says.

Further down the line, closer to water recipients themselves, there is a conceivable risk of localized cross-contamination if a sewage line crosses or runs alongside a pipe, according to Farajalla.

If “there’s a leak in the sewage pipe, this leaked sewer wastewater may find itself into the smaller … water pipe if that pipe is not full of water,” Farajalla said.

Sometimes those water pipes are not full because of electricity-driven interruptions in the flow of water through the networks’ branches. However, he added, “the residual chlorine” still in the water could kill off the bacteria even if cross-contamination were to occur.

System-wide contamination of the water network is a “very, very low probability,” Farajalla said, adding that, for now, the public should avoid panic. “Especially in Beirut,” the country’s largest customer base for water supply, “you should be confident” that state-provided water is clean.

In some other areas of the country, however, Farajalla said “there is a question mark at times.” For his part, Nasr adds that people should not worry about state-provided water in the north because it is “controlled and monitored.”

Asked about the risk of cholera contamination via water networks, BMLWE director Jean Gibran told L’Orient Today that “until now, there is no danger.”

However, another risk could arise from people relying on private water delivery companies to supplement the supply from the government, Nasr and Farajalla warned. The private water companies are not regulated, and their water quality is not necessarily tested with the same level of scrutiny as government supplied-water.

Contaminated water from a private provider that gets pumped into an apartment building’s reservoir could contaminate that reservoir. Customers should demand to see test results from private water providers before filling up their tanks, Farajalla said, with Nasr also warning about unknown water quality in unmonitored wells and springs.

Nazih Bou Chahine, associate professor at the Lebanese University and director and founder of the National Center for the Quality of Medicine, Food, Water and Chemicals, previously told L’Orient-Le Jour that water from private sources should be brought to a full boil for at least one minute. If boiling is not possible, chlorine can be used to neutralize the bacteria that causes cholera.

Farajalla said most people in Lebanon should feel comfortable continuing to shower in government-provided tap water and do dishes and laundry.

But until the cholera outbreak subsides, it might be wise to use bottled water for teeth brushing, he says, and parents might want to use bottled water when cleaning small children’s faces, given their poor ability to keep their mouths closed while bathing.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect Gaby Nasr's role as the head of the technical department at the North Lebanon Water Establishment (NLWE). A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Nasr is the head of the NLWE.