A photo taken from a drone shows trucks blocking the public road in Dora, at the northern entrance to Beirut, on Feb. 2, 2022. (Credit: Issam Abdallah/Reuters)

BEIRUT — It was the summer of 1997 and postwar reconstruction was in full swing when an engineer by the name of Yasser was appointed vice chairman of the board for the most important institution involved in rebuilding the country, the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR). Yasser’s brother, Nabih, also had reason to be feeling fortunate — the previous fall he had won his first re-election as speaker of Parliament.

Twenty-five years later the two Berri brothers remain in their respective functions.

Members of the CDR board are appointed by and can be fired “at any time” by the cabinet. Under the 1977 decree that established CDR, board membership was initially supposed to be for three- to five-year terms. In 2009, however, the cabinet allowed the then-incumbents to remain in place until it decided on replacements, something that has not happened in the intervening years. With two board members having died and one having resigned, the board, which ought to have seven to 12 members, now contains just four.

A representative of CDR did not respond to L’Orient Today’s question of whether the board can still reach a quorum.

The small number of actors involved and the long timespan in which they remain in office appear to have helped political elites extract rents from CDR contracts over the years, according to a new study by Mounir Mahmalat and Wassim Maktabi, researchers at Lebanese think tank The Policy Initiative.

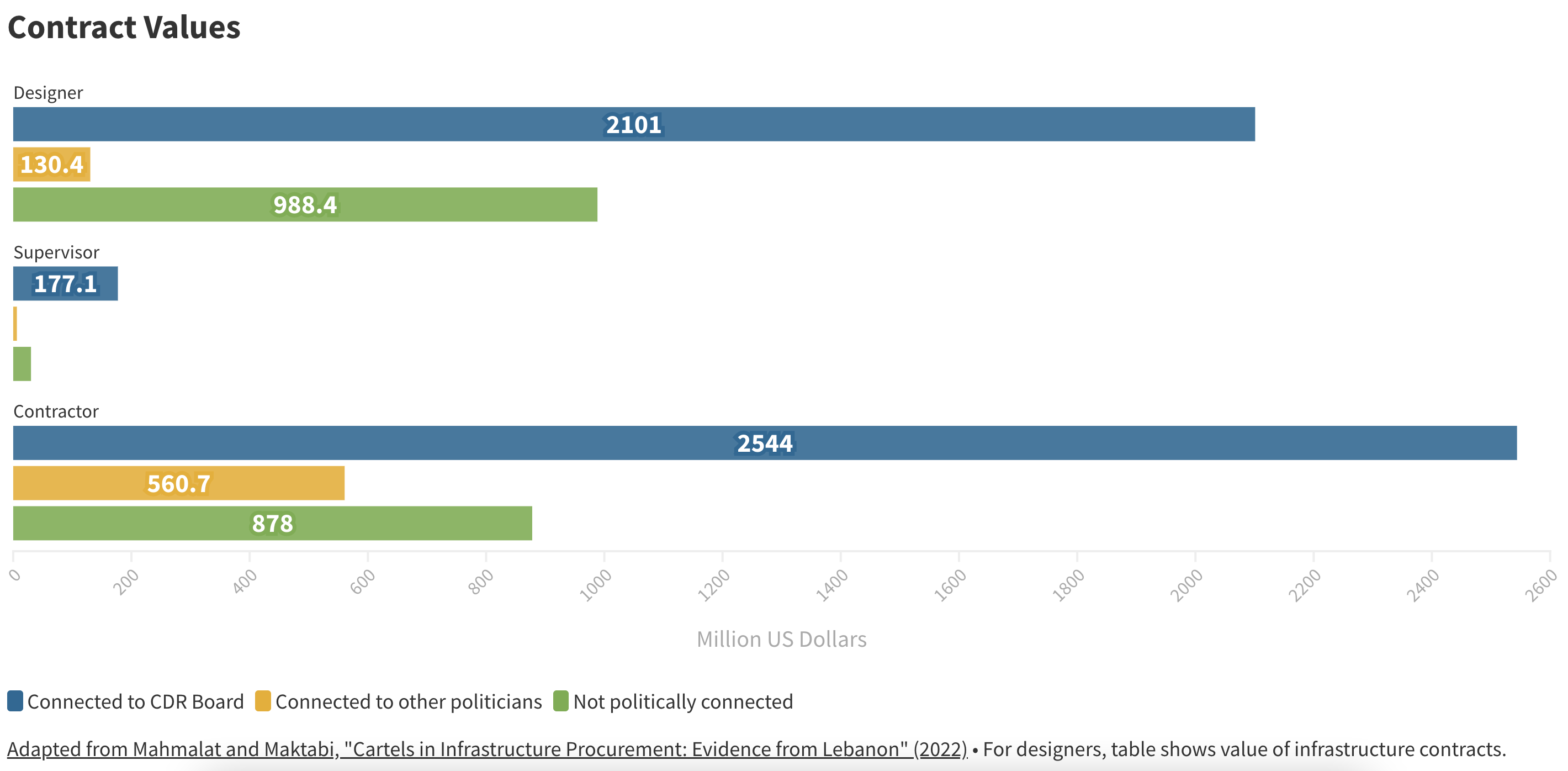

In a pair of studies, the researchers examined all 394 infrastructure procurement contracts awarded by CDR between 2008 and 2018, totaling nearly $4 billion in payments to contractors.

A total of 135 firms applied for these contracts but the 23 percent of firms with a direct political connection to a CDR board member brought in 64 percent of the dollars meted out.

The researchers defined a political connection as the CEO or at least one board member of the company being a politician or a “close relative” or “publicly known friend” of one.

However, they found that not all political connections matter. Firms with connections to CDR board members were significantly more likely to win contracts, but those with connections to other political figures not directly involved in running CDR appeared to be of little help in getting CDR contracts. The 15 percent of firms that were connected to a politician without a direct representative on the CDR board netted just 15 percent of the contract dollars awarded.

The key to this phenomenon, they found, involves understanding how the “cartels,” as the researchers referred to networks of companies, bureaucrats, and politicians that extract rent from procurement processes, actually coordinate.

A representative of the CDR contacted for comment on the report, said they had not read the report and were unable to comment.

How the procurement process works

Like other procurement institutions globally, when the CDR wants to implement a project they hire a design consultant to draw up the technical specifications for the project, including the criteria the contractor needs to meet. For instance, bidding on a contract could be limited to companies that have previously been awarded a CDR contract of a minimum dollar amount in the same sector in the past five years. The design consultant also helps CDR evaluate the bids received and determine which bids should be disqualified from consideration.

For many contracts, even if the tender for the project will be bid on openly, the design stage will not be — only a handful of experienced and knowledgeable designers will be invited to bid on the contract to design the project.

This discretion is in line with global practice, as procurement staff cannot reasonably wade through dozens of design proposals. But it can be abused if designers craft the terms of the subsequent bidding so that the “correct” company wins, even while the bidding takes place transparently, the researchers say.

“You can have the most capable institution on the planet — and we are making it very clear that CDR is a very capable institution — you can have everything in place, but you will need to pay attention to those … intermediary steps in which there's still a sort of discretion available to elites to exert some kind of political influence,” researcher Mahmalat told L’Orient Today.

He added that international organizations and donor countries that scrutinize the bidding process in Lebanon tend to focus on “technical work to understand who bids, to evaluate bids, to make sure that the bidding amount is correct, and all these things” and so the role of designers “flies a little bit under the radar.”

But the TPI study found that the designers are crucial to the process. According to their data, even if a contractor is politically connected to members of the CDR board, contracts did not have their budgets inflated and costs overrun unless the designer was also politically connected.

That finding “actually is something that’s very positive, because it tells us that institutional functions are important and can't be circumvented,” said Mahmalat. “Even if you have power, you’re just not able to impose it to the extent that you would like to and even the powerful heads of these organizations … are not able to circumvent these institutional processes to the extent that they probably wish to.”

He added: “It also tells us something about this general argument that is often being made vis-à-vis Lebanese public administration, which is that everybody is corrupt and institutions are just dysfunctional. It’s just not true.”

Possible avenues of reform

The 2021 public procurement law could help close one channel of rent extraction, the TPI researchers argue. The law, passed in June 2021 and entered into force this past July, restricts the ability of state institutions to use lists of eligible bidders for a contract, opening the bidding to companies outside the network of politically connected contractors. This rule was already imposed on CDR by the World Bank for projects it funds, and Mahmalat and Maktabi found no systematic overpricing of those contracts.

Under the new law “the role that the designers will play is definitely attenuated,” said Maktabi.

Another crucial reform, the researchers argue, is returning the CDR board to its original format — seven to 12 members serving three- to five-year terms. Contract steering can only work when all the parties trust that a favor done today will be paid back tomorrow. A contractor might agree to let a contract go to a competitor and forgo millions in revenue on the condition that they would receive the next one. But a temporary board gives contractors far less confidence that the person they bargained with will still be there in the future to make good on promises. And a larger board gives them less confidence their contact can deliver what they promise.

“This deferred reciprocity aspect is something that is very tricky to maintain,” said Mahmalat. “If [contractors] don’t know that the people that they have to [put their] trust into will be in their position of power, in two years down the line they would never agree to it ... and moreover, if you know that there’s more competition in the board itself, then you might … have some doubts that the contact person that you have on the board is actually able to follow through and enforce the deal.”