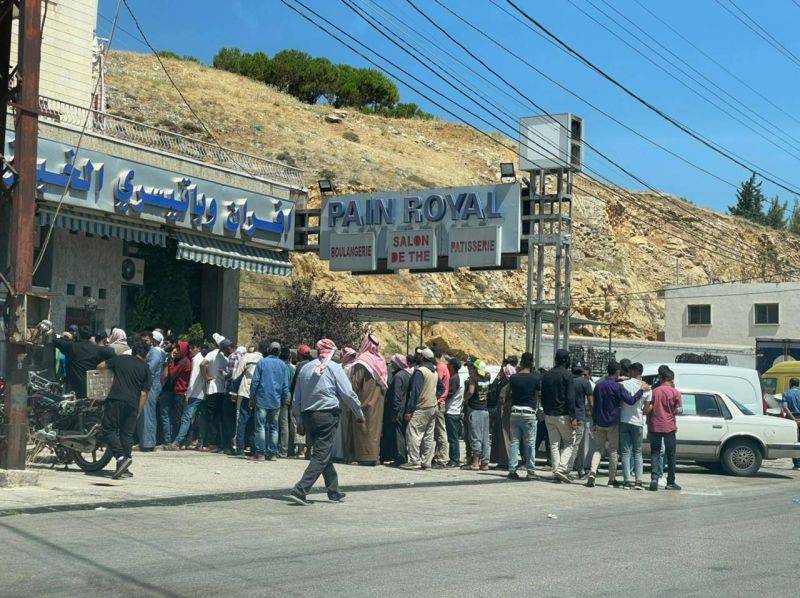

A line for bread in Qubb Elias Wednesday morning. (OLJ/Sarah Abdallah)

The latest shortage of bread — part of the long list of subsidized products in short supply over the past two years — has spurred the same seemingly endless queues in front of bakeries. The lines this week are not unlike those that blocked the roads in front of gas stations during the summer of 2021.

The search for bread, an essential commodity par excellence, has exasperated people across Lebanon, even more than the fuel.

In one video circulating on social media this week, young people are shown entering and destroying a Bekaa Valley bakery, which was clearly closed to customers. Meanwhile, some people are accusing Syrian refugees of trading bread on the black market.

The state still subsidizes the wheat used to make ordinary white bread. This wheat subsidy policy, established by the Banque du Liban at the beginning of the financial crisis, has allowed continued imports of this essential commodity — thanks to BDL financing wheat imports at a ratio of 100 percent in foreign currency, calculated at the official rate (LL1,507.5 per US dollar) since the spring of 2021, rather than at the parallel market rate (around LL29,500 in recent days).

The current bread crisis, many people fear, portends a lifting of subsidies, which would increase the price per bundle from its current LL16,000 to LL30,000 or LL35,000.

Speaking to L’Orient-Le Jour Tuesday evening, Economy Minister Amin Salam denied any rumors that the government could lift the subsidies. He even assured in a press conference that a breakthrough is expected “by the end of the week,” as some 50,000 tons of wheat are set to arrive in Lebanon.

A queue for bread at a bakery in Sidon. (OLJ/Mountasser Abdallah)

A queue for bread at a bakery in Sidon. (OLJ/Mountasser Abdallah)

Meanwhile, the past few days saw several incidents at bakeries in the Bekaa Valley, including in Ksara, Qubb Elias and Taalabaya. A dispute broke out in Qubb Elias in front of one bakery there as customers vied for access to available bread. Some customers resorted to fighting one another with sticks.

Several rumors also circulated Wednesday in the Bekaa Valley: According to some, bakeries in the region were meant to receive 80 tons of subsidized wheat the following day. Others said that the price per bundle would rise to $1.5, or the equivalent of about LL45,000.

“It is harsh because the consumption of [plain] bread has increased enormously in the Bekaa, since the manouche has become so expensive,” said a young man from Taalabaya who declined to be named.

For some people, the crisis has exacerbated their rejection of foreigners, especially Syrians. In Ksara, a resident interviewed by L’Orient-Le Jour accused “Syrian workers of organizing themselves, along with their relatives, as soon as they know that bread will be available in bakeries, in order to buy a maximum number of bundles, while the inhabitants of the region wait for their turn.”

This person eased his remarks, however, ensuring that “these are isolated cases, as there are thousands of Syrians in the Bekaa.”

A Taalabaya resident told L’Orient-Le Jour that he is “convinced that subsidized wheat is being smuggled to Syria.” He said the accusation has sparked a heated debate between Lebanese and Syrians on social media.

Smuggling to Syria is routed mainly through Arsal, where bread, purchased at LL16,000 per bundle in Lebanon, is sold at LL25,000 on the other side of the border, a local security source told L’Orient-Le Jour.

The bread crosses the border in vans loaded with about 10,000 bundles each, later sold in Syrian villages. Subsidized wheat apparently follows the same path, some 40 tons entering Syria every day at the Hawsh al-Sayyed Ali, a Syrian border village, according to the same source.

Revolted by this new shortage, a handful of women from the Bekaa burnt tires and garbage and sat down in the main Nasser Square in Baalbek. One of them accused bakeries of “monopolizing the bread in the region, knowing that bundles sell for at least LL50 000 on the parallel market.”

Women close off a public square in Baalbeck in protest of the bread lines. (OLJ/Sarah Abdallah)

Women close off a public square in Baalbeck in protest of the bread lines. (OLJ/Sarah Abdallah)

‘Jostled and harassed’

In Sidon, the bread crisis has spurred bizarre scenes. In front of one establishment called The Arab Bakery, staff had formed separate queues for men and women. Samiha, standing in the women’s queue, told L’Orient-Le Jour that she waits in the line for bread every day in order to feed her children. “I was jostled sometimes, and I was even exposed to harassment ... We are being humiliated every day,” she said.

As with other crises, the Lebanese are trying to cope by either adapting or even finding workarounds. Some people reserve their spot in line in front of the bakeries early in the morning, while others ask several members of their family to queue up in order to get as many bundles as possible — sometimes with the aim of reselling them. The shortage has given rise to a flourishing black market, similar to the days of the gasoline crisis in 2021. This is increasingly the case in Sidon, where those who prefer to avoid waiting in the queues instead pay the price of trafficked wheat. Mopeds often park on street corners with boxes of bread bundles ready to be sold at full price.

Ibrahim, one Sidon resident, said he recently purchased bread on the black market. “I was in a queue in front of a bakery, and there were about 20 people in front of me,” he said.

“A young man with a Syrian accent came and offered me some bundles. I followed him behind the bakery where he sold me three bundles for LBP 30,000 each, whereas a bundle is sold at LL16,000 in the bakery. But I didn’t care because I needed to feed my grandchildren. I would rather pay more than be humiliated.”

Afif said he paid LL35,000 for a bundle he purchased from a young man stationed a few meters away from a bakery, also in Sidon.

Elsewhere in the city, Oum Mohammad boasted that “she has never stood in a queue, neither for bread nor for gasoline.”

“They deliver the bundle to my doorstep for LL40,000,” she said proudly.

Translated by Joelle El Khoury.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour.