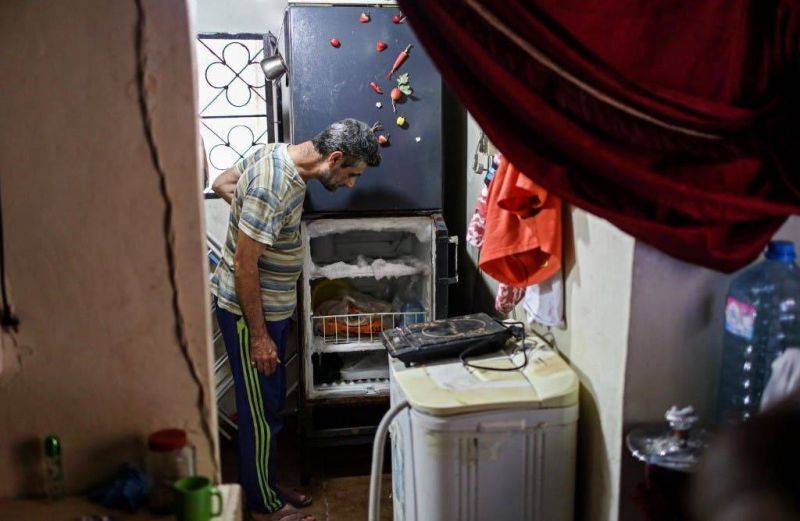

A Lebanese man looks at his empty refrigerator in Beirut in June 2020. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

Since Roman times, the tried and tested tools used by the ruling classes in order to appease the poorest have always been “panem et circenses,” or bread and circuses. And for the past three decades, Lebanon’s political circus has kept many a politician, pundit and plebeian much amused with a mix of spectacle, sectarian posturing and, every now and then, a gladiator match played out in the streets of the country. Amidst the political pageantry, the circus acts changed but one thing remained consistent: there was always enough bread to go around, until now.

This month, the price of a large bag of flat bread, which had cost LL2,250 (up from LL1,500 in June 2019 and LL2,000 in January), increased to LL2,500. In keeping with the government’s planned austerity platform — not least in its financial reform plan and 2021 budget — the move is just the latest in a string of policies by the ruling oligarchic sectarian junta to reckon with the fact that the subsidy regime long in place is now coming to the end. With any luck, so too will the political circus orchestrated by Baabda, the Serail and Nejmeh, and cheered on by their followers.

To be sure, the subsidy regime which supported basic staples such as fuel, flour and medicine (not to mention indirect subsidies on utilities) should have been replaced long before the perfect storm of financial crisis, pandemic and ammonium nitrate literally exploded in our faces. Blanket subsidy regimes are the preferred social protection band-aid policy for ineffective and lazy dictators and despots in our region, particularly because (until recently) they could afford to offer blanket subsidies through debt, oil revenues or a little bit of both. Lebanon of course pretended it could afford an unsustainable policy that sucked up as much as 30-40 percent of state expenditures each year, ballooned the public debt and allowed the political class and their banks to perpetuate their well-documented Ponzi scheme.

Not only is the subsidy regime wasteful, it is inherently immoral: blanket subsidy programmes benefit richer segments of society implicitly and proportionately more, because the rich already spend much less of their share of income on subsidized products. What’s more, subsidized products are often used to provide products used by the rich, not the poor (like fuel for Land Rovers and expensive croissants). Of course the little guy gets something, but its nothing when compared the cost of endemic corruption that typifies blanket subsidy schemes, not least in Lebanon. Subsidies themselves often initiate a vicious cycle when their cost leads to a debt crisis, which in turn eventually leads to their demise and removes the only form of support the poor had in the first place. Sound familiar?

In cahoots with many bankers, Lebanon’s ruling oligarchic junta, who profited from the status quo, have taken steps to implement an alternative policy required to make social spending more sustainable or useful to the poor. For decades, they have resisted calls to reform the taxation system and the National Social Security Fund so that a universal rights-based social protection system could be put in place. Instead, our heavily indebted government might now take out yet another loan to the tune of $247 million from the World Bank to implement a targeted cash transfer program for 786,000 Lebanese over three years.

While targeted cash transfer programs are not as harmful as blanket subsidy programs, they are not a replacement for universal social protection. To boot, the program will be paid out to Lebanese families in lira at below market rates (at LL6,240 to the dollar), while the government must pay back the World Bank in US dollars. While there are measures planned to reduce corruption and favoritism during the implementation of the scheme, there is little doubt in anyone’s mind that the sectarian junta who seek to appease their loyal followers will try to manipulate a system that is based on proxy means testing and incomplete data. Should they succeed, the loan will only be used to further entrench patronage in Lebanon, further in debt the government and eventually become yet another façade of Lebanon’s so-called social protection policy. But there is another way.

By our calculations, merely reaching the average tax potential of similar middle-income countries could generate an additional $3.5 billion per year. Raising the top tax rate from the dismal 27 percent to the OECD standard of 40 percent would generate an extra $6.82 billion a year — which would be more than enough to cover the implementation of a universal social protection scheme. If more funds are needed to kickstart that scheme, every 1 percent of wealth tax in a country where the richest 10 percent command around 55 percent of the country’s wealth would garner an additional $2 billion.

Earmarking those funds for social protection instead of financing a Ponzi scheme, requires a more progressive tax regime, lifting of banking secrecy, capital controls and a sacrifice from the ruling junta to give up the spectacle of subsidies for the substance of social protection. Indeed, Lebanon’s junta may soon find that, once out of their latest confinement, “panem et circenses” will no longer be tenable. After all, if there is no show, the spectators and unpaid performers eventually turn on the circus masters.

Sami Halabi is director of policy at the Beirut-based think tank Triangle

This article was originally published in French in L’Orient-Le Jour.