Lea Baghamian, 20, works as a policewoman in the Bourj Hammoud district, while studying architecture. (Credit: Bertrand Lenoir)

As a child, Lea Baghamian absorbed Armenian conversations among her classmates during school recess, eager to expand her vocabulary.

At eight years old, Baghamian relocated with her family to Bourj Hammoud.

Growing up in this vibrant Armenian neighborhood, she naturally blended her native tongue with Arabic and French, even in conversations with her parents and sister.

This linguistic amalgamation, however, hindered her full mastery of Armenian. “I felt somewhat disconnected from my peers, but it never made me feel excluded,” said the now 20-year-old policewoman, proudly wearing her Lebanese flag on her uniform.

While she embraces her dual identity, Baghamian finds that her Armenian heritage is most deeply rooted in her involvement with the Church, where she sings and plays the cello, finding solace in the spiritual guidance that has shaped her life, long preceding language.

This scenario would have seemed improbable 30 or 40 years ago.

Aline Kamakian, a third-generation Armenian-Lebanese, reminisced about her upbringing in a household where Armenian was the primary language.

“I grew up in a family where Armenian was spoken, with two brothers with whom we went to school, scout meetings and church in Armenian,” said Kamakian, owner of Mayrig restaurant. “It was a foregone conclusion.”

While Armenian continues to be prevalent within familial settings, its necessity for integration into the community has diminished.

The language’s decline is unmistakable: Western Armenian, a variant unique to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Egypt (as opposed to Eastern Armenian spoken in Armenia, Russia and Iran), was designated as an endangered language by UNESCO in 2010.

Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. Firstly, the widespread use of English, fueled by the pervasive influence of social media platforms, has played a significant role.

Additionally, the once-dominant Armenian population in the Middle East, which numbered over 200,000 in the mid-twentieth century, has dwindled to an estimated 40,000-60,000 in Lebanon today.

Moreover, there is a growing trend of assimilation among the younger generations, who primarily speak Arabic.

Pillar of identity

The Armenian-Lebanese community has invested considerable effort in preserving their language within their adopted homeland.

Originally hailing predominantly from Cilicia, they arrived in Lebanon as Turkish speakers or speakers of Armenian dialects influenced by Turkish, Arabic and Persian. Their migration to Lebanon followed the devastating genocide of 1915-1923, which claimed over a million lives.

Gathered in camps, they increasingly adopted Western Armenian to distance themselves from Turkish, solidifying the language as a cornerstone of their identity. Advocacy for Armenian language instruction proliferated, laying the groundwork for what would evolve into the world’s largest network of Armenian schools.

Two generations later, Western Armenian reached its zenith.

“It was in the 1960s that there were the most books, newspapers, schools, theater and even cinema in Armenian,” said Tigrane Yegavian, a researcher at the Institut chrétien d’Orient. “Lebanon was then the beacon of the Armenian diaspora in the world.”

Following the “Ottoman model,” Lebanon’s division into communal groups fostered this cultural blossoming, where language reigned supreme. Neighborhoods, endogamous marriages and political parties like Tachnag contributed to this vibrant Armenian identity.

However, the tumultuous events in Lebanese history have disrupted this established order.

Decline

Like their fellow citizens, Lebanese Armenians endured massive emigration during the 1975-90 Civil War and subsequent crises that have plagued the country since 2019.

This mass exodus has led to the depletion of the community and stifled intellectual vibrancy. The most visible consequence of this decline has been the dwindling number of Armenian schools.

“In the 1950s, there were 56 schools, each with hundreds of students. Today, we only have sixteen,” said Ara Vassilian, headmaster of the school operated by the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), a diaspora organization established in Cairo in 1906 and a pivotal figure in Armenian affairs in Lebanon.

According to the 2019 Armenian Diaspora Survey, a quarter of Lebanese Armenians never enrolled in Armenian schools.

“This statistic highlights the evolving landscape within the community, considering the extensive school network that Armenians in Lebanon have cultivated within a concentrated geographical area,” according to the survey.

Ara Vassilian, principal of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) school, in his office in Antelias. (Credit: AZ)

Ara Vassilian, principal of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) school, in his office in Antelias. (Credit: AZ)

Intermarriage has emerged as another contributing factor to assimilation, further exacerbating the decline of the language. Although official statistics are lacking, various indicators suggest a rise in intermarriage rates.

Vassilian observed a notable shift at a school where he has served since 1993. “Approximately one out of 15 students came from a mixed marriage 10 years ago,” he said. “Now that ratio has surged to ‘half or more’.”

“The new Armenian is undoubtedly an individual with a multifaceted identity, and we must acknowledge and embrace that,” he added.

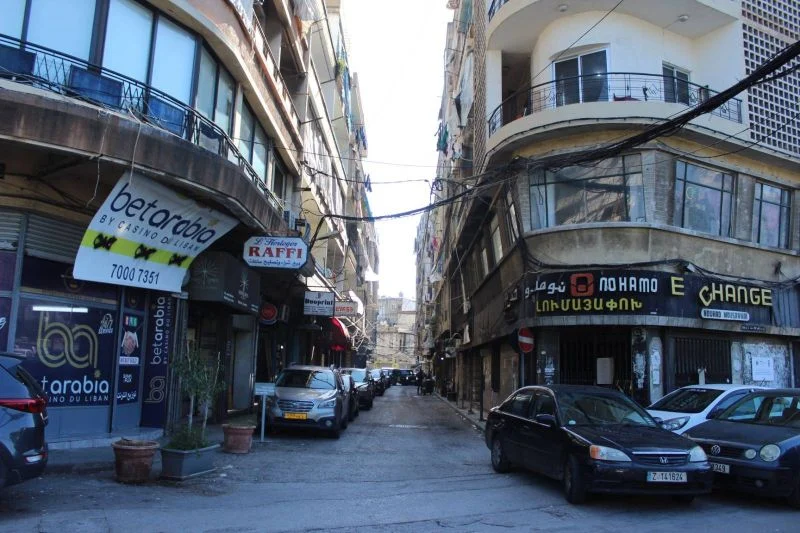

In the Bourj Hammoud neighborhood, the social landscape has undergone significant transformation. Within just over a decade, Kurds, Syrians and Ethiopians have migrated into the area, drawn to its affordable rental properties. Once renowned as the historic epicenter of the diaspora, Bourj Hammoud has shed its ghetto status.

“The era when fluency in Armenian sufficed for interactions at the butcher, the grocer, or the tailor is a thing of the past,” said Vassilian. Over the past two decades, the community has dispersed to Lebanese towns like Antelias, Fanar and Rabieh, nudging Lebanese Armenians toward Arabic, French and English.

In Anjar, a resilient linguistic enclave on the fringes of the Bekaa Valley, “the local Armenian dialect bears heavy Arabic influence,” said Antranik Dakessian, Professor of Armenian Studies at Haigazian University.

In the backdrop, there’s a prevailing notion that Armenian is associated with tradition, while other languages, especially English, are linked to the future.

Linguist Anaïd Donabedian-Demopoulos, a professor at Inalco, highlighted this dynamic.

“Armenian is employed to discuss Armenian topics, values, a manner of existence within the Armenian sphere,” she said. “When addressing subjects like sex or politics, English is favored, whereas discussions on matters like marriage or religion are conducted in Armenian.”

Vassilian is striving to address this dynamic. “The students are passionate about football, so I initiated an educational project focused on the sport. This enables them to learn terms like ‘pass,’ ‘header’ and ‘goal’ in Armenian, facilitating discussions in our language rather than resorting to English translations on their phones,” he explained.

However, implementing such a method beyond the classroom setting proved challenging.

“While there exists a plethora of high-quality Armenian-language publications, as individuals progress in their education and pursue higher studies, Armenian gradually recedes from the intellectual sphere, media and discourse on contemporary issues,” said Donabédian-Demopoulos, who taught at the American University of Beirut from 2013 to 2016.

Juliette Baghamian, Lea’s sister, attributes this trend to generational shifts.

“Our grandparents, who faced fewer challenges in securing stable employment, could dedicate their efforts to preserving the language, which was a community imperative back then. For us, the primary focus is on securing well-paying jobs, particularly in times of economic downturn,” said Juliette, a psychology student at the Lebanese University.

‘If the wellspring runs dry’

“I would rather characterize it as change rather than detachment,” said Dakessian, “because while Western Armenian may be on the decline, Armenian culture remains deeply ingrained within families.”

At Haïgazian University, Dakessian encounters numerous students who did not attend Armenian school but enrolled in his course on Armenian medieval arts.

“Young people express their identity through alternative avenues, with history playing a pivotal role.”

For instance, Léa Baghamian proudly recalls her participation in protests outside the Azerbaijani embassy during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, “because we have already endured genocide.”

However, for Yegavian, the linguistic estrangement and disengagement are primarily indicative of a broader disintegration within the community.

“While civil society remains active, it comprises individuals rather than a cohesive Armenian structure capable of charting a new course,” Yegavian said. “This issue necessitates both resources and a coherent agenda.”

According to the Armenian Diaspora Survey, 48 percent of respondents in Lebanon cited the lack of vision as the primary challenge confronting the community, on par with concerns about mixed marriages.

“Lebanon and Syria serve as breeding grounds for Armenians, many of whom eventually migrate elsewhere in the world. These individuals often assume roles as educators, administrators and clergy,” Yegavian said, noting that the sole seminary outside the United States is located in Bikfaya, in the Metn District.

“If this wellspring runs dry, it could mark the demise of the post-1915 diaspora,” he said. “It would also signify the end of Armenian advocacy for justice, a century after the genocide. The stakes couldn’t be higher.”

A view of the historic district of Bourj Hammoud, where signs in other languages stand alongside those in Armenian. (Credit: Hermine Nurpetlian)

A view of the historic district of Bourj Hammoud, where signs in other languages stand alongside those in Armenian. (Credit: Hermine Nurpetlian)

This article was originally published in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translated by Sahar Ghoussoub.