The NSSF building in Beirut. (Credit: NNA/File photo)

BEIRUT — After nearly 20 years in the works, Parliament has finally passed a law amending Lebanon’s social security system, and converting its existing end-of-service indemnity system (EOSI) into a pension scheme.

The new law was minted in the Official Gazette on Dec. 28 and will launch in about two years if all goes according to plan.

The move could have positive implications for the economy down the line, Mohammad Karaki, director general of the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) which will run the new pension scheme, told L’Orient Today.

The new pension scheme marks a significant milestone for Lebanon, which stood as “one of only two countries in the Arab region without a scheme that protects insured workers with long-term periodical benefits for retirement, death and disability,” according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), which helped design the new system. The only other country in the Middle East without such a scheme is Palestine.

The law also significantly reshapes the structure of the NSSF, reducing its administrative board from 26 to 10 members, and appointing a group of experts to oversee its investment operations.

Originally passed in 1963, the EOSI system, a one-time payment for retirees at the age of 64, was only meant to be a temporary transition to a monthly pension system once funding was secured, but instead remained the closest thing to retirement benefits in Lebanon after decades of failed attempts to amend it.

As Lebanon’s economic crisis drags on, questions regarding sustainably financing the reformed system are yet to be fully answered, considering the government’s tight budget and the deteriorating socio-economic situation.

Still, the inclusive nature of the new pension system, developed with extensive support from the ILO, means that it will be open to everyone from private sector workers to self-employed individuals and expats abroad, on the condition that they enroll in the system, Karaki told L’Orient Today.

The end-of-service indemnity system vs. the monthly pension scheme

Under the EOSI system, as L’Orient Today explained in an earlier article, individuals receive a one-time payment upon retiring, which is calculated as follows:

If Worker X made an average monthly salary of LL1.5 million (or the equivalent of $1,000 prior to 2019) and retired after 30 years of NSSF enrollment, they would receive their salary multiplied by their years of service (LL1,500,000*30) plus half of their salary multiplied by their years of service, minus 20 (LL750,000*(30-20)), or a total of LL53 million ($35,000 at the LL1,500-against-the-dollar exchange rate that was effective back then). Today, that same amount would be worth $595 at the LL89,000 rate.

Karaki highlighted that around 400,000 individuals — private and public sector workers not covered by the civil service fund — have been benefiting from the current EOSI system. He expects millions of workers, from all professions, to benefit from the new pension scheme upon its launch, a significant increase compared with the old system.

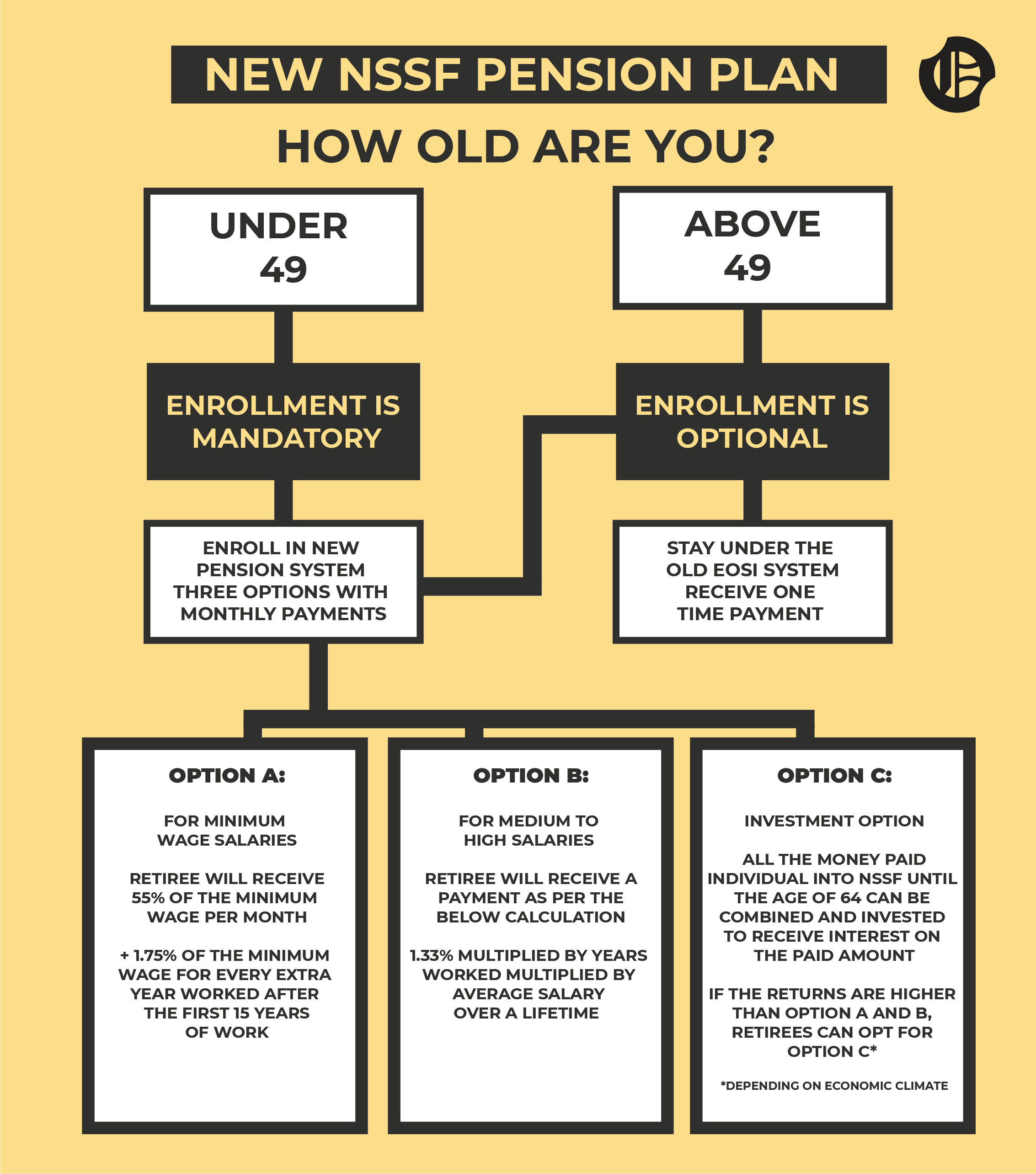

Moving away from a one-time payment, the new monthly pension system promises to offer three options to its enrollees upon retirement:

Minimum A: This is targeted at individuals who make close, or slightly above, the minimum wage during their lifetime.

If Worker A (let’s call her Leila) worked for 15 years (the minimum number of years to benefit from this option under the new law), she will receive 55 percent of the minimum wage (set at the time she retires) on a monthly basis until she dies. If she works for longer than those 15 years, Leila can expect to receive 1.75 percent of the minimum wage for every extra year, up to a maximum of 80 percent of the national minimum wage.

So if Leila worked for 22 years (for example), she can expect to get paid 55 percent of the minimum wage + (1.75%*(22-15)*minimum wage. Taking into account today’s minimum wage of LL9 million, her total could be LL6.05 million per month.

Minimum B: This is targeted at individuals who make medium-to-high salaries. Worker B (let’s call him Abdo) can expect to make 1.33 percent for every year he worked, multiplied by his average salary, adjusted for inflation, over a lifetime. So if Abdo worked for 30 years, he can expect to receive 40 percent of his average salary (1.33%*30 years). Assuming his average salary was LL30 million, he can expect to get paid 1.33%*30*LL30 million, or a total of LL11.97 million per month, for the rest of his life.

Individual Savings Account: This option is targeted at everyone and will depend on the returns made by the NSSF through their investments, which would require a healthy economy and a good investment climate at the time of payout.

Luca Pellerano, Senior Social Protection Specialist at the ILO, explained to L’Orient Today that a portion of a worker’s contribution will go into a virtual individual account which should generate its own specific returns until the time they retire at the age of 64. These returns would then be converted into a monthly pension. However, under no circumstances can this pension option be lower than Minimum A and B. Should the individual account fall below them, then the higher of the two minimums will be the one applied and be paid to the worker instead.

All monthly salaries will be indexed to inflation, said Karaki, noting that monthly payments will increase or change according to the required inflation adjustments.

Pension payments will additionally be transferable to an individual's spouse and children upon the enrollee’s passing. The spouse can benefit from the monthly payments until he or she remarries or dies, after which the benefits will be passed on to the children.

The children may in turn keep cashing the payments until they reach the age of 18, or even 25 should they still be students. However, the law mentions no age limit for children with disabilities.

Age groups to benefit differently from the new system

Enrollment will apply to each age group differently. For individuals under 49 years old at the time the new pension system goes into effect, enrollment will be mandatory.

However, for individuals aged 49 and up, enrollment will be optional. They will be given the choice to either stay under the old EOSI system or join the new pension scheme. Should they choose to move to the new system, Karaki explained that the NSSF will transfer previous fees collected from the individual, and combine it with upcoming fees paid under the new pension system. People who are 64 years or older and have not cashed out on the old one can join the new system and will have their pensions calculated based on the number of years of contributions they made to the old system. That sum will be split into monthly payments for the retiree's pension.

According to Pellerano, people above 64 who have not yet cashed out their end-of-service indemnities will also have the option to join the new pension scheme if interested. However, he believes very few of them will. Additionally, those who have not yet retired at the time the new scheme comes into force will have the option to join.

People above 64 who have already cashed out their end-of-service indemnities and choose to start working again may join the new scheme and start contributing anew. Their pensions will be calculated according to the number of extra years they work after rejoining the labor force.

Karaki expects both systems to work in parallel over the course of 15 years, after which the EOSI system will officially come to an end, leaving the new pension system as the sole one in the country.

Pellerano explained that there is no provision in the law for a retroactive application of the new pension system.

“The NSSF considered, a few months ago, the introduction of a transitional arrangement that would allow retirees who cashed out their end-of-service indemnities since 2020 to return them and join the new scheme,” said Pellerano.

But the current law does not provide that option, and he believes this to be a problem that the relevant institutions may want to take into consideration during the issuing of upcoming decrees.

A win-win situation for employers and employees?

Under the current EOSI scheme, every worker in Lebanon is entitled to a certain amount of money upon retirement. The NSSF collects bits and pieces of that amount from that person’s various employers throughout their career. It is the job of their final employer to cover the last chunk of that retirement sum — that last chunk is called the “settlement payment.”

The salary adjustments that followed the economic crisis caused Lebanese lira EOSI benefits to increase drastically, leaving a significant burden on last employers, who saw their settlement payments skyrocket.

Officials hope the move to a new pension system will solve this problem altogether for employers, while workers are expected to also start paying their NSSF contributions on a monthly basis. This comes in contrast to the current system, where employers only contribute 8.5 percent of their employee’s monthly salary to the end-of-service fund.

Pellerano told L’Orient Today that the new law stipulates the final contribution rate to the NSSF to be set as part of an upcoming implementation decree “because it will be calculated on the basis of the prevailing economic conditions and the revised actuarial projections.”

Actuarial science is the understanding of the evolution of the demographics of the insured population on matters such as life expectancy and family structures, but also through assumptions on the evolution of the economy and the labor market.

Based on projections, Pellerano and his team estimate that to keep the new system sustainable for the next 100 years, employers and employees need to make joint contributions ranging between 16 and 17 percent of the employee’s salary. This number is double the current 8.5 percent, paid by employers only.

The monthly fee that workers and employers can expect to pay is yet to be determined through the decree that will be issued one year after the law was published in the Official Gazette.

Employees, who according to Karaki currently hold six to 10 jobs over the course of their careers, will be able to shift from one employer to another with more ease and a feeling of security, as their move will no longer impact their retirement benefits, he argued.

Financing the new scheme

The new scheme will have three main sources of financing.

First are the leftovers from the NSSF, the contributions made by employers and employees, and the interests generated by the investment fund.

Karaki estimated the total amount currently available at the NSSF to be around LL30 billion — a mere $333,000 at the current exchange rate.

When the EOSI finally ends after 15 years of running in tandem with the new pension system, all the remaining amounts will also be moved from the old to the new system, on top of the monthly contributions that the NSSF plans to collect from employees and working individuals — hence adding to the funds of Lebanon’s pension system.

The previous law limited the NSSF’s ability to invest in assets such as treasury bills and fixed-income classes in the Lebanese economy.

Under the new law, there will be no restriction with regard to investment diversification that can be carried across the Lebanese economy and outside of it, in both lira and foreign currency.

“While the pension system can only receive contributions and pay benefits in Lebanese lira, the new law does not set any limit or currency constraints as to the range of investment choices that the NSSF will be able to undertake, ” explained Pellerano.

The new law established a new investment committee of six experts who will oversee the investment department.

“We project that the NSSF will accumulate significant resources, but this will require diversified investments in the system’s early years [...] it’s important that the investment function of the NSSF is properly managed,” said Pellerano.

Pellerano stressed that the new system is designed in a way where contribution rates and the investment returns of the fund, as projected by the ILO, ought to be sufficient to finance the pension scheme without any additional government intervention. The state, however, remains the ultimate guarantor of the scheme.

Due to its partly redistributive nature, the pension system will in its early stages entail current workers and pensioners to share the burden to ensure retirees receive the necessary social benefits amid Lebanon’s economic crisis, added Pellerano. But over the years, the ILO expects the system to be readjusted gradually.

The new system will take around two years to be fully implemented after its publication in the official Gazette, said Karaki, who is aiming for a launch in 2026 if everything goes according to plan.

The NSSF plans to announce a new administrative board in around six months, as well as a new investment committee and director of investments, to foresee the institution’s future operations.

Karaki estimated that an online platform will be launched in around a year, making it easier for people to enroll in the new system, pay their future fees and receive real-time updates and information on the interests accrued and the state of their individual accounts as well as their overall pension benefits.

“The law will require an independent actuarial valuation to be conducted every three years to ensure a healthy functioning of the fund. There are strong elements in the law that require external independent auditing and all documents and reports should be made publicly available,” added Pellerano.

As trust in public institutions remains very limited in the aftermath of Lebanon’s worst economic crisis, it remains to be seen how this new, rather ambitious system, unravels in the next two years.

To learn more about the new pension scheme, check the Q&A sheet put together by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Lebanon and the NSSF here.

This article was amended on Jan. 12 as detailed here:

-The law also significantly reshapes the structure of the NSSF, reducing its administrative board from 26 to 10 members, and appointing a group of experts to oversee its investment operations. (the word "investment" was added).

-Minimum B: This is targeted at individuals who make medium-to-high salaries. Worker B (let’s call him Abdo) can expect to make 1.33 percent for every year he worked, multiplied by his average salary, adjusted for inflation, over a lifetime. (the words "adjusted for inflation" were added).

-Workers are expected to also start paying their NSSF contributions on a monthly basis (we replaced the word "taxes" with the word "contributions").

This article was amended on Feb. 1 to reflect the options available to different age groups under the new scheme in light of new information shared by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Lebanon.