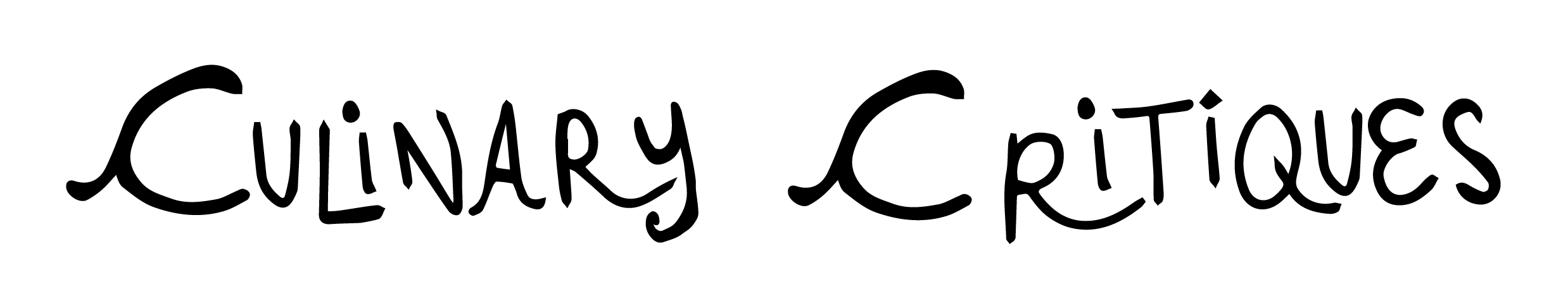

“Al-Moulatham,” one of the two paintings by Ayman Baalbaki withdrawn from the Christie's sale on November 9, 2023. (Courtesy of the owner)

Al-Moultham (the veiled one) and Anonymous, two paintings created by Ayman Baalbaki, were unexpectedly removed from the catalog of Christie’s biannual sale of Middle Eastern art, originally scheduled for Thursday, Nov. 9 in London.

The first piece, a large acrylic on canvas (measuring 200 x 150 cm) dating back to 2012, portrays a man with his face concealed by a keffiyeh. It was initially valued at an estimated range of $98,000 to $150,000.

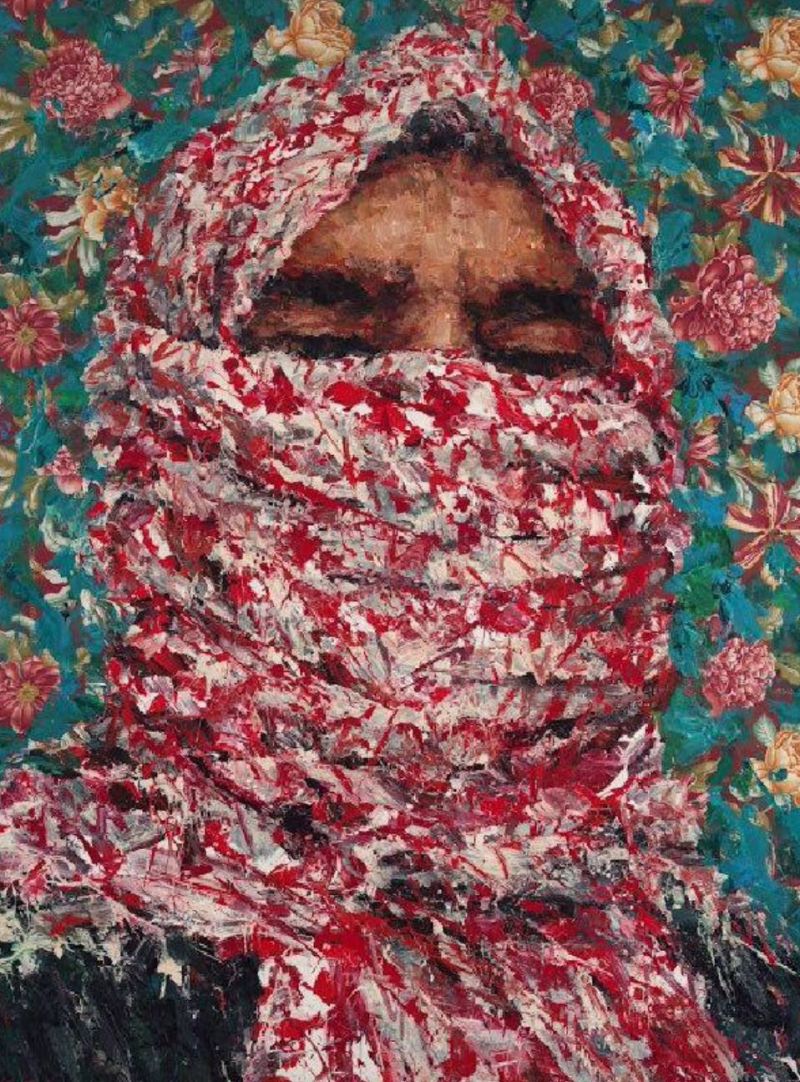

The second artwork features a man wearing a gas mask with a red headband on his forehead, bearing the word “thaeroun” (meaning “rebels”) written in Arabic. This piece is part of a series of small-format artworks (each measuring 70 x 50 cm) inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings, which the Lebanese artist created between 2011 and 2018. Also an acrylic on canvas, the piece was estimated to be worth between $15,000 and $22,000.

A painting entitled “Anonymous” from the eponymous series produced between 2011 and 2018. (Courtesy of Ayman Baalbaki)

A painting entitled “Anonymous” from the eponymous series produced between 2011 and 2018. (Courtesy of Ayman Baalbaki)

These two artworks, both owned by different Lebanese collectors, were consigned to the renowned international auction house through its Middle East representatives.

“The representatives themselves approached me and insisted on including my painting in their sale,” the owner of al-Moulatham stated in an interview with L’Orient-Le Jour on the condition of anonymity. However, the decision to withdraw the painting originated from Christie’s New York office.

The collector expressed his disappointment, saying, “It is not supported by any clear arguments, as my contact only mentioned that the decision was made due to numerous complaints they had received, without specifying the nature of these complaints to me.”

“I’m deeply saddened by this incident,” the collector said. “I never expected an auction house of Christie’s stature to prevent the sale of a work solely based on its connotations.”

He suggested that this self-imposed censorship is connected to political tension around the conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. What’s more, after the decision to withdraw the paintings, Christie’s allegedly referred him to its private collectors’ department, where someone was willing to offer “a very good sum for this painting,” he claimed. However, he declined the offer. “As this painting has gained even greater value in my eyes after this incident, I no longer wish to sell it,” said the owner.

A vague justification

The owner of “Anonymous,” who was not formally informed by the auction house about the withdrawal of his painting, faced a similar situation. “I discovered it myself by checking the online catalog, and when I inquired for an explanation, I received a vague response,” the seller said.

Both collectors were unofficially informed that Christie’s had taken this action to “safeguard the works from potential adverse publicity in the media.”

This unusual course of action is challenging to justify. Typically, an artwork consigned for auction is withdrawn only when expert assessment reveals it to be a forgery or if there are concerns regarding its provenance, such as links to money-laundering networks. None of these conditions apply to the two paintings in question.

When contacted, the director of Christie’s Middle East department simply responded through a communications officer, that “sales decisions are confidential matters between Christie’s and the sellers.”

Record prices for artworks

Baalbaki characterized the controversy affecting his work as “censorship without a name.”

“They aim to censor a particular art, a specific Arab culture,” Baalbaki said. “This situation brings to mind the concept of ‘degenerate art’ used by the Nazis to suppress the creations of Jewish or Communist artists with modern approaches, under the pretext that they insulted German national sentiment.”

This sense of outrage is especially justified since it was the Moulatham series, inspired by the events of 1975 in Lebanon (the same year of Baalbaki’s his birth) and initiated in 2006, that played a pivotal role in establishing the Lebanese artist’s international reputation.

His recurring portrayals of the feda’i (freedom fighters ready to sacrifice themselves) donning the keffiyeh scarf, contributed to his recognition a prominent figure in the Middle East’s contemporary art scene.

Baalbaki’s recognition was further solidified through record-breaking sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams.

The ban on selling a keffiyeh painted by an Arab artist raises questions about double standards in the art world. Keffiyehs by Israeli Jewish artist Tsibi Geva are displayed in prominent museums like New York’s MoMa and Jewish Museum. This prompts reflection on whether we are entering a time of increasing fragmentation, where even artistic expression, losing its freedom, faces confinement within narrower boundaries.

Despite their disappointment, artists and collectors from the Arab world remain hopeful. Bassel Dalloul, one of the region’s most influential collectors, is concurrently auctioning several works from his collection at Christie’s on Thursday, Nov. 9.

In the catalog for the sale, titled “Marhala: Highlights from the Dalloul Collection,” an untitled painting by Baalbaki has not encountered the same fate as the other two paintings. Dating back to 2009, it portrays a destroyed and bombed-out building, evoking the imagery often seen in news reports from Gaza.

An untitled Baalbaki painting dated 2009, that did not suffer the same fate one's censored at Christie's. (Courtesy of the Dalloul Foundation)

An untitled Baalbaki painting dated 2009, that did not suffer the same fate one's censored at Christie's. (Courtesy of the Dalloul Foundation)

Asked about his personal stance on the “Baalbaki affair,” the collector from the Dalloul Foundation expressed his deep disappointment with Christie’s actions, making it clear that he conveyed his concerns to those responsible.

He sees it as a form of censorship targeting Arab art, at a time when such art is gaining international recognition and interest. Major museums are even inviting artists from the region to participate in their exhibitions. He believes that any response should be well-considered and measured to avoid creating chaos that could potentially play into the hands of those opposing their interests and have adverse effects on the art market.

“Of course, we can legitimately boycott and resort to legal action, but it seems to me more fruitful to favor an informative and educational approach to the art of our region,” he said. “By explaining, for example, that the keffiyeh is a scarf that dates back to the Egypt of the Pharaohs. And that it has always been worn by the people of the region to protect themselves from sand and wind. And by Jews in particular in ancient times.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.