A view of Mar Mikhail as seen from Gemmayzeh, after the Beirut port blast of Aug 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — “I don't think we use the word resilience once.” Zeina Saab pauses. “We’re tired of that word. It’s not something we’re proud of, but the stories show people coming together, supporting each other. That's what we wanted to evoke.

“The country’s broken on multiple levels, not just from the explosion. The social fabric is completely destroyed. People are divided. Politicians are exploiting us. Why does it take tragedy for beautiful things to happen between people?”

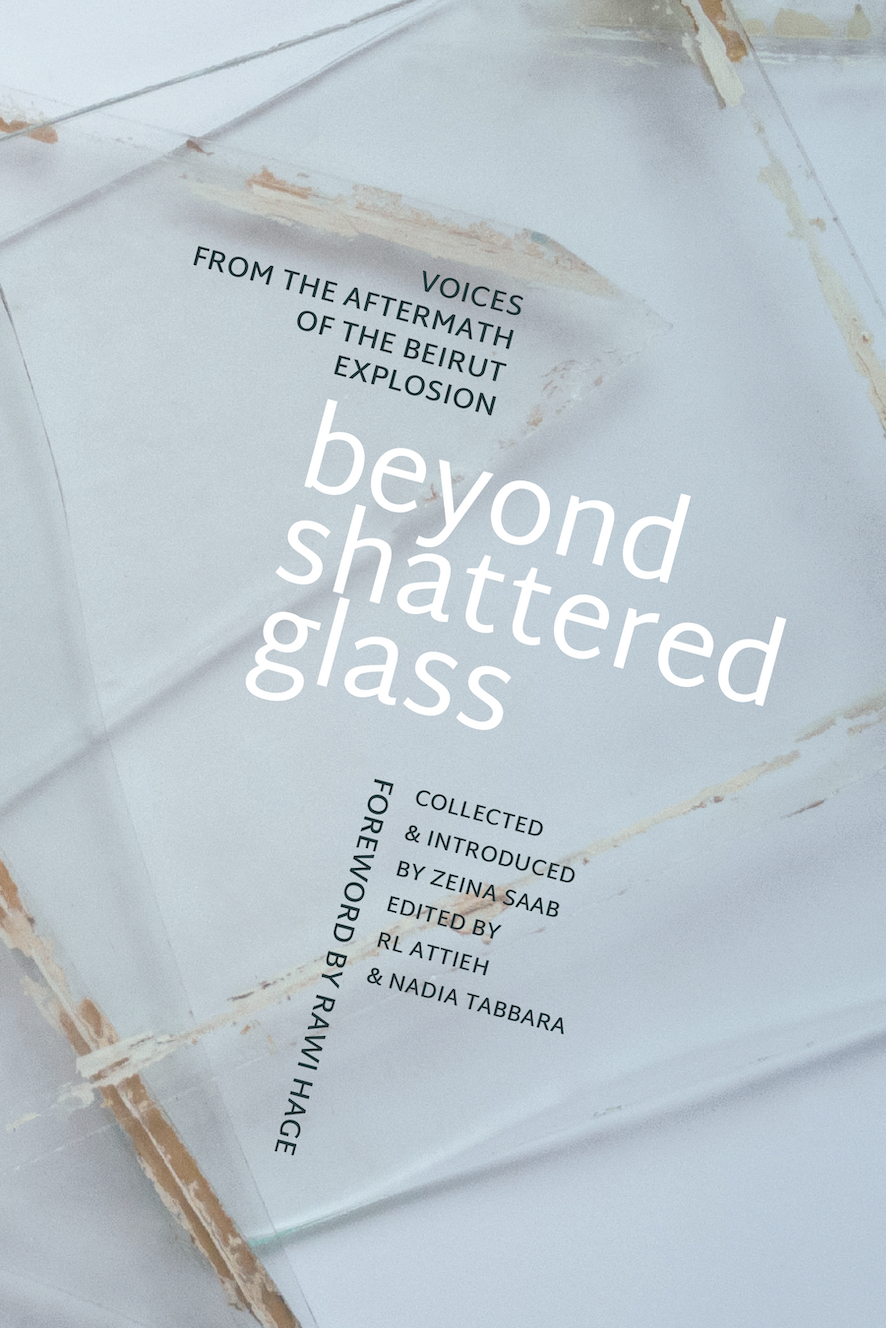

In the spring of 2021, Zeina Saab decided to document the stories of individuals living in Beirut’s port-side neighborhoods on Aug. 4, 2020. Titled Beyond Shattered Glass, the collection will launch Sunday evening at an event in Beit Beirut. All proceeds from the project — book sales and ancillary fundraising initiatives — will go to port blast survivors.

Saab has been active in Lebanon’s development sector for some years, founding an employment initiative for creative youth in 2012 called the Nawaya Project. She is not a professional writer, so she assembled a team to get the job done.

A couple of days before the launch of Beyond Shattered Glass, Saab chatted with L’Orient Today about the challenges confronting the completion of this book, the voices she felt compelled to preserve in it and the rage that sustained it.

Storytelling

Three survivors of the Beirut port blast of Aug 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Three survivors of the Beirut port blast of Aug 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Beyond Shattered Glass is being released by Interlink, a US publisher that caters to international audiences. Saab and her team had originally planned to self-publish, but the project’s supporters encouraged them to find a conventional publisher to maximize distribution.

“I’m not a writer,” she reiterates. “I’ve never released a book before, but [the process] was surprisingly positive. We didn’t have to contact too many publishers before [Interlink’s] Michel Moushabeck expressed an interest … When we started, we never expected that this book would go global. So we’re very grateful for that.”

Beyond Shattered Glass is comprised of 22 stories clustered into three themes — survival, strength and solidarity. When selecting stories, Saab says she and her editors sought to reflect the broad swathe of Beirut’s social fabric.

“Each story reflects how people came together to save lives and to support each other in some way, despite everything they might have experienced in Lebanon in terms of discrimination or racism,” she says.

“We have stories of Lebanese, Lebanese Armenians, Syrians, Palestinians, Ethiopians, Filipinas, the elderly, people from different religious and socio-economic backgrounds,” Saab says. “We have the story of a young, deaf boy — now a young man. It’s not directly stated that he’s deaf but it stands out in the writing, so the reader can work it out. At one point, he wonders how loud it must have been. This is so jolting for all of us who heard the explosion — you wouldn’t imagine not hearing it — but what must it have been like for people who can’t hear?

“We do what we can in each story to take people through each person’s personal journey.”

One of the greatest challenges Saab faced was deciding which stories to exclude from the volume.

“There are thousands of stories that deserve to be told,” she says. “We only were able to use 22 of them. That was really difficult for me, because every story is invaluable.

“I felt that writing the introduction would be cathartic for me, a way of letting everything out. Then it ended up taking a slightly different path, talking about the many stories I’d heard that aren’t in the book. I felt this was a way to recognize the fact that we couldn’t share everybody’s stories here.

“It was very challenging for a lot of the writers, I think. We poured our all into writing something that we truly would love to see on the page, but things need to be cut. You learn to trust that the editors know how to preserve the integrity of each story.

“I had a relative pass away from the explosion and I had mentioned her in the introduction. There was feedback that I should take that out and focus on something less personal. That was difficult. This was a very personal project for me, but it’s not my book. It’s a collective effort. I had to accept that this is a book that is unfinished.”

Another challenge stemmed from how to render the oral histories on paper.

“Initially we wanted to have each person submit their story. I formed a team with Nadia Tabbara and RL Attieh and a few others. We asked, ‘What is our objective? Is it to have people write their stories and accounts?’ That’s a beautiful project, but this book probably won’t go very far, because they’re not professional writers. They don’t need to be and shouldn’t be: Everybody has their own strengths. Since the objective is to have as many people as possible read these stories and to remember what happened, then they must be well written.”

They called in 21 professionals, including Tabbara, to write up the survivors’ stories. Their number includes filmmaker and writer Mary Jirmanus Saba, journalist Kareem Chehayeb, writer and Rusted Radishes founder Rima Rantisi, and artist and writer Zena el Khalil.

“There was some concern that the stories would no longer be seen as authentic or true to [the survivors’] experience. So we worked hard to ensure that this was creative nonfiction, true to what the contributors told the writers. They did a beautiful job. Nadia is a brilliant creative writing coach. She worked with every writer and reviewed their drafts and gave them feedback. Every contributor reviewed and approved their story.”

Memory and Change

Zeina Saab. (Credit: Sarah Shmaitilly)

Zeina Saab. (Credit: Sarah Shmaitilly)

Another challenge Saab says she felt was how Beirutis eventually got back to their lives, disrupted as they’ve been since the fall of 2019, as though the outrage of what they’d experienced had been normalized.

“Aug. 4 happened and we were all devastated,” she says. “After some time, you felt like the city somehow moved on, but we didn’t. We worked on this book for three years. Aug. 4 was a constant experience for us because we were talking about it all the time with the writers, with the contributors, reading the stories over and over.

“That was difficult. It was a continuous grieving process for us and very anguished. It was something I felt I needed to do. I could not just move on and forget. That’s not to say that people who’ve moved on have forgotten. But I personally needed to do something to make it clear that this was not okay. I have not moved on with my life. I don’t think I’ve healed. I don’t think any of us can actually heal without full justice and accountability.”

She pauses.

“The day before we had to submit the final manuscript to the publisher, I re-read all 22 stories in one day. It took me about seven hours, and I was a wreck by the end of the day. I felt like I had experienced Aug. 4 all over again.

“It made me go back and review my introduction … It had initially ended on a note that we must never forget, but maybe we have to move on and come to terms with what happened. At the end I wanted to keep my anger in the introduction.

“I think that’s what’s interesting. The more time passes, the easier it is to just accept what happened and not be as angry. These doses of reality, reminding us of what people went through, are important to get the anger back. That’s what I channeled into my introduction towards the end. If I had my way, I would have had so much more, but there’s a time where you just have to let it go. The book is out there now. We hope that it resonates.”

Beyond Shattered Glass ends with a chapter that looks past the blast itself, to the possibility that criminal negligence on this scale might play a role in bringing some positive change to Lebanon.

“I didn’t want people to think ‘Okay, so this tragedy happened. Now what?’ ‘From Rage to Change’ talks about the USJ [Saint Joseph University] elections that happened some months after the explosion and how students from the university medical school channeled their rage into the student elections. For the first time in history, they actually won.

“It’s not promising too much,” she says. “We don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s just enough to get people to think ‘Okay, what else can we do?’”

Beyond Shattered Glass will be launched at Beit Beirut on Sunday, Aug. 6, 6-8pm. It is published by Interlink. All proceeds and donations will be distributed among port blast survivors.

(Courtesy Interlink)

(Courtesy Interlink)