‘Horseshoe Coffee.’ Amin Al-Basha, 1972. (Credit: Courtesy the Amine El Bacha Foundation)

BEIRUT — “We targeted a lot of service drivers. I told them, ‘Take two copies. One stays in your car, because we want people who enter your car to be able to flip through this book — you know, like when they go to a hairdresser. The other one you take home. Do whatever. Sell it if you want.” Nadine Touma chuckles. “Then of course you have the ones who are like ‘I don’t read. Beirut is dead. Lebanon is shit. I want to leave the country. Screw you all!’”

In the midst of the publisher’s salon sits a small desk, where she says artist Jorg Abou Mhaya has been at work illustrating a Dar Onboz title, Acine Chatawi’s debut poetry collection. About the desk, mingled with plants and assorted personal items, the room is festooned with artifacts of Touma’s past and ongoing projects.

Among these is a small 624-page Arabic-language book titled Beirut 360. Drawing upon the work of artists (from the contemporary to the ancient) and writers — from disciplines as diverse as history, archaeology, geology, architecture and design — Touma & Co cast their nets widely before spearing the publication’s 360 bite-sized entries about the titular town.

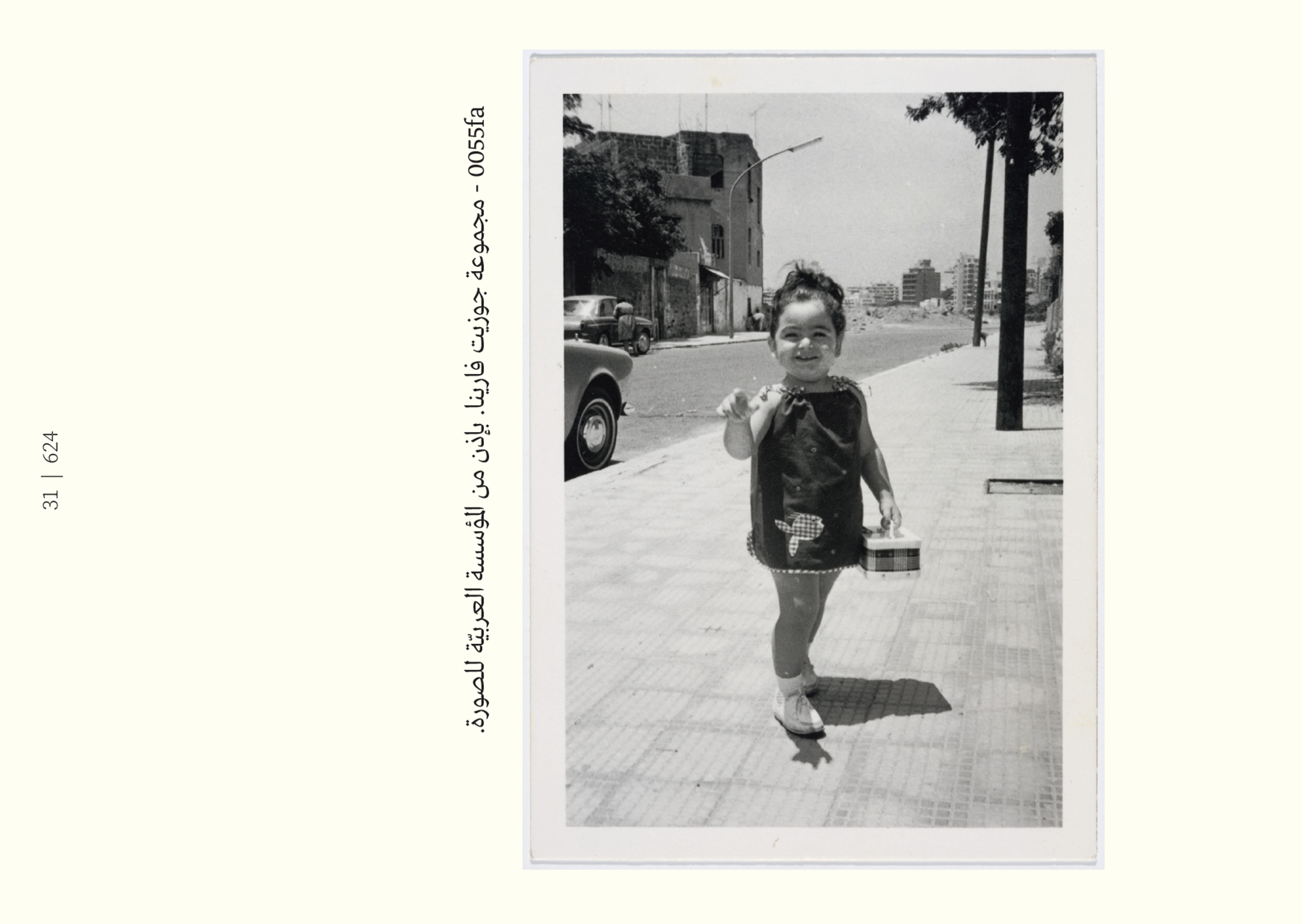

‘Roaming’ (Credit: Josette Farina Collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation)

‘Roaming’ (Credit: Josette Farina Collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation)

The apparent contradiction of breadth and brevity is assuaged by the poetic tone of Beirut 360, echoed in Touma’s explanation of the title.

“There are three reasons,” she begins. “The most obvious is that when you shift perspective, you go 360 degrees, the sense that Beirut [provokes] our curses and bitching and hate and love and schizophrenia.

“360 because you have 360 [units] in the year divided by four seasons, if you want it to have lunar accuracy in your counting of the days.

“The third reason is ... if you look at the sun, it is for everybody. It’s not for the rich or for the poor. It’s not for any religion. It’s for anybody who happens to be on that spot, on that Corniche, and they can see that sunrise from behind Jabal Sanin and then go down in the sea that same day ... It so happens that the moon also rises from behind that mountain and also happens to set in that sea. Beirut closes its circle daily.”

From exhibition to book

Beirut 360 was devised as a component of “Allo Beirut?,” Beit Beirut’s sprawling multi-media exhibition. The space’s director Delphine Abirached Darmency wanted the show’s interactive exhibits and parallel public program to combine facets of outreach and pedagogy.

“It’s interactive. It’s activities. It’s debate. There’s lots of layers,” Touma says. “So you have that one pillar, which is targeted toward groups and schools.

“Then you have what I call tajwal [roaming], a beautiful word that evokes the flâneur. I asked particular people — in the theater, in the music scene, in architecture, in the history and archaeology scenes — to give particular tours. They’re not guides. They’re like artists that take people to the places in the city that inspire them. Visitors discover the city in ways you wouldn’t read in a book. The tour always includes a meal or dessert typical of Beirut.

Posing before the St Georges Hotel. (Credit: Faisal Al-Atrash Collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation)

Posing before the St Georges Hotel. (Credit: Faisal Al-Atrash Collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation)

“The third pillar is the book. I was telling Delphine that in addition to activities in situ, you also need to expand, hence tajwal, which completes the exhibits ... This book talks about everything. It talks about the post-war destruction of our history and it talks about the [civil] war, but it doesn’t have to talk about them in ways that we’re used to. When you have a whole series of articles about the memory of a city that doesn’t exist anymore, and places that have disappeared — from the Turkish baths to the Grand Theatre to what happened to Piccadilly to the lighthouse — you’re actually retracing this ‘human history.’

“This book [targets] a wide audience but we’re not into nostalgia. Beirut 360 is not crying over the past. For me, it shows that, firstly, we don’t come from a void. In the absence of any pedagogical tool in schools, or universities that is accessible and beautiful and interesting, people don’t know the history of this city … Doing the work that we do over the last 20 years, I believe that this [knowledge] heals.”

Language is a major facet of accessibility.

“Most art and cultural institutions do not have anything in Arabic — texts, titles, descriptions,” Touma says. “You take it for granted ... I am very picky about language, and I kept telling the translator, I’m not ticking the box of ‘It’s in Arabic.’ I’m ticking the box of ‘It’s understandable, comprehensible, intelligible Arabic.’

“This is the case with so many texts in art and archaeology and history. I really know this language,” she adds, “but I don’t get these texts. If we had to translate into Arabic, how do we translate them? Which words, what tone? How close is the writing to the rhythm of speech? These are important questions, if you want to make a book appeal to a wide audience, one that a university professor and a hairdresser can enjoy equally.”

Sivine Ariss and her colleagues disseminating copies of ‘Beirut 360.’ (Credit: Dar Onboz)

Sivine Ariss and her colleagues disseminating copies of ‘Beirut 360.’ (Credit: Dar Onboz)

Beirut 360 was released on the last weekend of June. It commenced with an onsite launch — two pairs of musical readings on Saturday and Sunday at Beit Beirut — and continued with mobile dissemination of the work. Touma, her creative partner Sivine Ariss and a few colleagues coursed through the city’s various neighborhoods in the back of a vintage vegetable delivery truck, handing out free copies of the book.

“I’m a big fan of storytelling,” Touma says, “of turning any text into a story, even if it’s not narrative. Then we did several rounds of the city in the truck with cases of books and a megaphone. Again, it was a tajwal, a meandering ... We were calling for us to know the history of the city and to celebrate it.”

A garden

Touma’s salon is not far from Lebanese University’s Faculty of Fine Arts and Architecture, in Furn al-Shubbak, near the location of the month-long Christmas market the publisher hosted in December 2022. In a gesture of creative magnanimity, Dar Onboz provided a space for artists, artisans and designers to exhibit and sell their work, commission-free.

Three years into a financial crisis that has beggared most of the population, and with the cost of living rising avariciously, it is exotic indeed to get something for free in this town. It provokes curiosity about the health of Dar Onboz as an enterprise.

“It’s beautiful!” Touma smiles.

She blinks.

“Two things. I think the crisis and my health gave me the momentum to say, ‘Fuck it. What do we have to lose?’

“The same thing happened with the garden. Everybody says, ‘You’re crazy, going to the municipality, entering a whole world of madness and corruption. I’m like, ‘You know, I had the luck to be raised by a family that made me believe that you can write your own history. I’m gonna go write my own history.’”

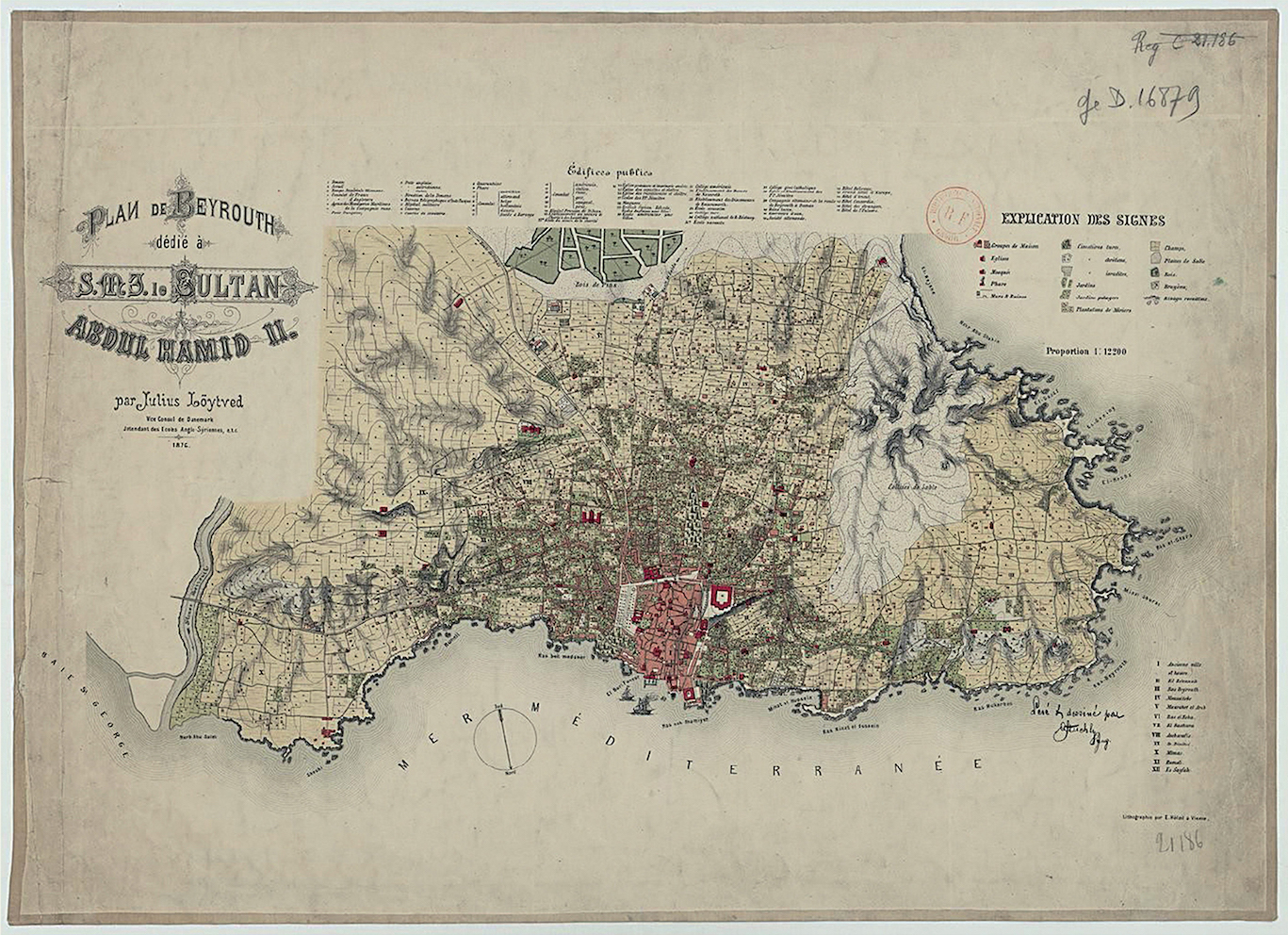

Map of Beirut dedicated to Sultan Abdul Hamid II / Julius Loutvid, 1876. (Credit: Dar Onboz)

Map of Beirut dedicated to Sultan Abdul Hamid II / Julius Loutvid, 1876. (Credit: Dar Onboz)

Fifteen seconds from the venue of Dar Onboz’s Christmas market, by Touma’s estimate, the 3000-square-meter garden plot is located adjacent to LU campus and the nearby hospital. Touma has pieced together a history of the green space from the research of a neighbor, Lebanese author and educator Charif Majdalani, and an urbanist friend who shall remain anonymous.

“Geologically, Fun al-Shubbak contained ponds and marshes,” Touma says. “It has wells and is actually very rich in water.”

The garden had originally been much larger and was owned by a Lebanese order of nuns, who had operated a hospital and old age home on the current site of the fine art campus. The nuns endowed the land and a decree was subsequently issued that it must remain a public green space — partly violated during the Civil War when the hospital was built. It seems the municipality opened the space as a public garden around 2000.

Touma says she and her colleagues have taken over management of the garden for 10 years, on a renewable basis, and have been actively working on the project for about four months.

“The municipality kindly offered us water and electricity, and the freedom to program cultural events here,” she recalls. “We started at the most basic level: Humans, I’m sorry, you’re secondary. The earth needs help. The trees are not okay. We need to start loving the space before we make it public, but also teaching people how to respect public spaces. They’re not just places of entertainment and play. They can be places of contemplation, where you can pick and eat a cucumber, observe different varieties of trees and listen to birdsong.

An ancient Araucaria tree in Dar Onboz’s soon-to-be-public garden. (Credit: Dar Onboz)

An ancient Araucaria tree in Dar Onboz’s soon-to-be-public garden. (Credit: Dar Onboz)

“We didn’t change its architecture,” she adds. “We had many ailing trees but we saved all the ones that are still alive and discovered something very special. When we walked through the garden during COVID, I found a majestic tree there, so beautiful. It turns out it’s on the endangered list and needs to be protected. Its genome is among the most ancient of pine trees.”

Touma’s team has made a few additions to the garden to make it a more flexible venue — a clay oven for baking bread and some cement tables. Dar Onboz is accepting donations to pay the gardener and the person redesigning the grounds.

“We are going to have an incredible program of workshops with a wide variety of people. We are designing the garden as permaculture [an agricultural ecosystem developed to have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems]. We’re hoping it will be a garden of learning and knowledge, where people can understand how to plant things next to each other and how they relate. We’re also hoping to stage a series of concerts. The downstairs space will serve food and show work by local artists and artisans.”

Touma smiles. “That’s Dar Onboz, anchored with two spaces. We want to create a cultural center that doesn’t really exist in this city — a space for conversation, a multidisciplinary laboratory.”