Deir Ezzor-born Maram (center) wants to help rebuild Syria one day. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

SHATILA, Lebanon — There’s barely a dry eye to behold in the decaying building’s fully packed room. A standing ovation is punctuated by excited shouting and the occasional zaghrouta. The group of kids on the stage are beaming with pride. As they should, after all, they’ve just performed Shatila Palestinian refugee camp’s first opera, From Dawn to Dusk.

The opera, or rather the operetta, was written, composed and performed from scratch in less than five days. Although most of the kids had never sung in public before the first day of practice, during their performance they were confidently belting out their own lyrics. The project was a collaboration between the local NGO Alsama Project, British-based Garsington Opera and the Grange Festival, with the Florence-based Mascarade Opera Foundation.

After performing a small encore of both the Lebanese and Syrian national anthems, followed by what they describe as “the Alsama song,” some of the performers walk up to Karen Gillingham, creative director at Garsington Opera, and alternately thank her and give her a hug. She is visibly touched.

Richard Taylor, the opera's musical director, warms up the crowd. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Richard Taylor, the opera's musical director, warms up the crowd. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“The main difference with the kids I work with in the UK, although they’re wonderful too, of course, is that the ones in this group have shown each other nothing but unconditional support,” Gillingham says. “I suspect this is partly due to the fact that they’ve already been through so much at such a young age. But they were an ideal group to work with, as a director. They were so eager to participate.”

Created from their own “memory banks” as Gillingham calls it, the opera materialized as a result of the youths writing their own poetry and accompanying compositions – turning them into songs.

“I was supposed to be teaching them,” Gillingham says, as tears well up in her eyes. “But they were the ones who ended up teaching me. We can learn so much from them.”

One of the performers, 15-year-old Hussein, who studies at the Alsama center and at a government-run school, doesn’t show the slightest trace of nerves a short while before the opera is set to begin. “ I can’t wait to show what we’ve been working on,” he says excitedly. Although he has yet to see an opera, and admits that he doesn’t know much about the art form, he is happy that it was introduced to him and the others. “It was a great way for us to express our feelings,” he says. “And it made our group feel even closer. We became even better friends.”

Wissal, who’s also 15 and lives in Shatila, agrees: “If you’re in a bad mood, it makes you feel better to express your feelings in this way,” she says. “And if you’re in a good mood, it helps to come in and feel even better.” She aspires to be an actress one day, because she loves expressing her feelings in this way, she says, although in her immediate future she would like to be an international cricket sports ambassador. Hussein, meanwhile, writes his own lyrics and dreams of being a rapper “like Drake or Travis Scott.”

From windows to poetry

One of the key exercises while developing the opera was to have the kids look through windows all over the world on the online Window Swap platform. Afterwards, they were asked to write poems, based on the things they remember seeing when they would look through their own windows when they were still living in Syria. Most of the kids arrived in Shatila in 2014 from Syria’s northeastern Deir Ezzor and Raqqa, both of which were captured by Daesh (Islamic State) at the time.

Wissal chose to write a poem based on what she sees from her current window instead. “But it’s not the window in my house,” she says. “It’s my emotional window … the window in my soul.”

What she sees, Wissal says, are three stars. “These stars represent my education, Alsama and cricket. And these three stars give the power to the moon to fight the darkness, which is the ignorance in my society.” Her poem and the poems of the others are performed throughout the opera.

“When I came to Lebanon one and a half years ago, I didn’t even know how to read and write in Arabic,” Wissal says. “Now I write poetry in English. And poetry is another language to express your feelings,” she adds with a beaming smile.

The British creative team was assembled by Maximilian Fane, president of the Mascarade Opera Foundation, who had already met the students last year, rehearsing a song with the kids after hearing about Alsama through his mother who works with the organization. Fane has big plans to turn the improvisational opera into a more elaborate affair. Not only is it going to be performed at the Garsington opera next summer, he is determined to find a way to have it reach one of the most scintillating stages in the world: the temple of Bacchus at the Baalbeck International Festival.

Audience members applaud the opera performance. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Audience members applaud the opera performance. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

“Although I’ve found that creating an opera with the kids is an ideal way for them to express their feelings, I want to make it clear that this is not meant to function as a therapy session,” Fane says, insisting that when you show children they are given agency, they will embrace it.

After the performance, the kids clamor for a blonde woman to join them on stage. She seems almost uncomfortable by the attention but grants their wish anyway.

Continuity is ‘the main essence’

She turns out to be Meike Ziervogel, one of the co-founders and current CEO of Alsama. Ziervogel, a writer who has her own publishing company in London, came to Lebanon in 2019 with her husband for a yearlong sabbatical, mainly to do volunteer work. When the year had passed, she realized she didn’t want to leave and could contribute more in Shatila. This led to Alsama, which she co-founded with Kadria Hussien, a Shatila resident herself.

“It started out as a small empowerment center,” Ziervogel says. “Empowerment, some yoga, a bit of creative thought and cricket.” Now, Alsama is a full-fledged educational center, not just for Syrian refugees but also Palestinians and Lebanese who have found themselves locked outside of the regular school system. “Most of them come to us completely illiterate. We’ve now developed our own curriculum so that in six years, we’re making up for the 12 years they've lost.” The classes are geared towards ensuring that the kids pass the Lebanese brevet exams in three to five years.

How do they manage to do that? “We teach 44 weeks without break,” Ziervogel says, alluding to the fact that refugee children in the country have dealt with irregular schooling in the past two years due to COVID-19 related school closures, teacher’s strikes and general funding issues.

According to a donor presentation compiled by Alsama in October, based on UN and Human Rights Watch statistics, more than half of Syrian refugee children in Lebanon between the ages of three and 18 are not in school.

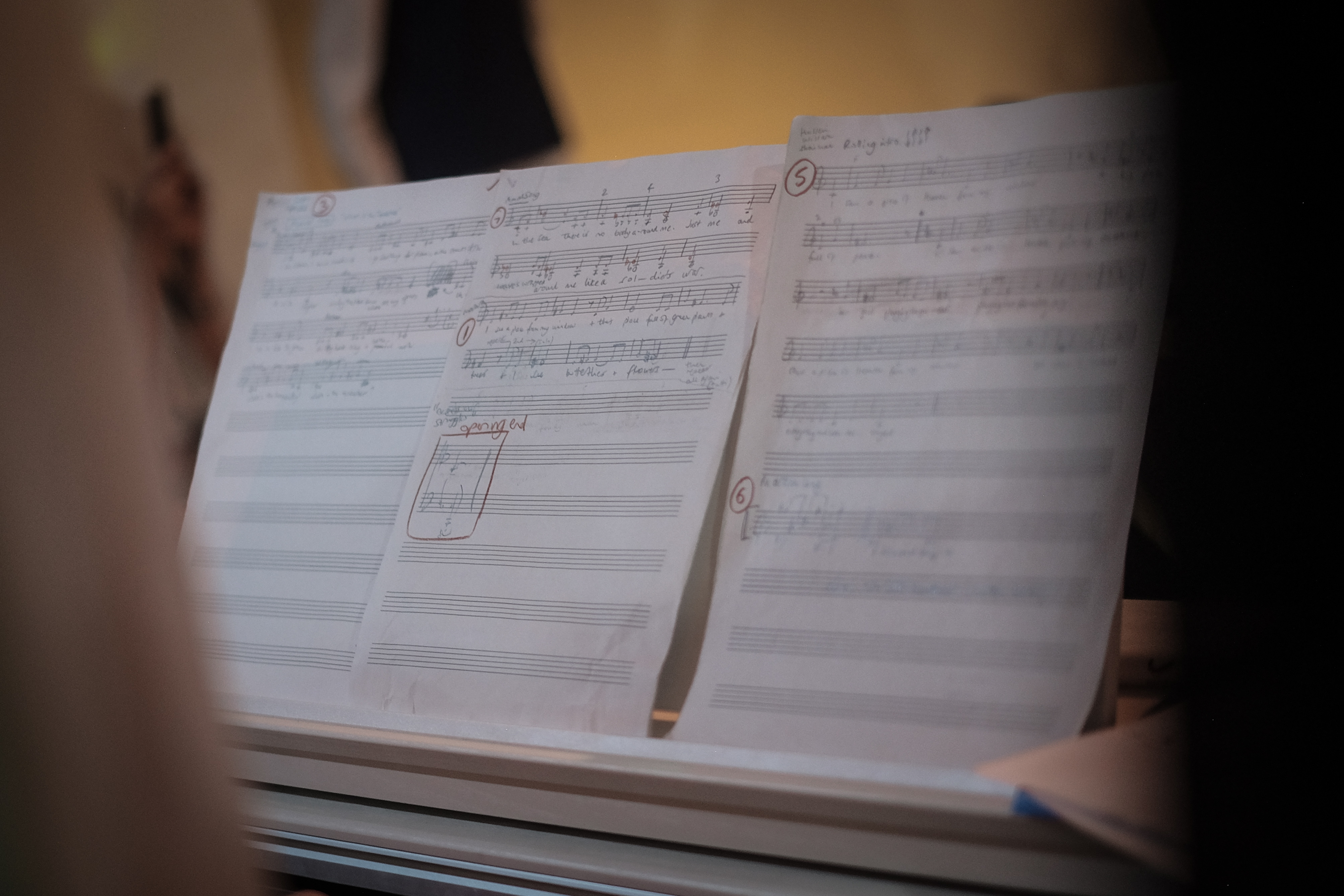

The participants wrote their own lyrics and composed the accompanying score. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

The participants wrote their own lyrics and composed the accompanying score. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Both Wissal and Hussein are assistant coaches for the Alsama cricket team, while most of the other kids performing in the opera play on the team as well.

Ziervogel says that she’s aware of the scrutiny many NGOs, both local and international, receive. “That’s why I’ve always said that we can’t and won’t make promises we can’t keep. The main essence, when it comes to education, is continuity. Especially for these kids who have fallen through the cracks,” Ziervogel says. “So when we offer something, we make sure it’s going to stay open and last.”

Ziervogel initially funded Alsama with her and her husband’s own money.

However, as the institute has greatly expanded since its inception, they now have partnered up with like minded trusted institutions, such as the Malala Fund. “At the moment we have two institutes, one here in Shatila and another in Burj [al-Barajneh], and in April 2023, we’re going to open another institute,” Ziervogel says. “So we’ve been able to teach double the students.”

One of those students, Deir Ezzor-born Maram, and a natural theater star judging by her earlier performance, is joking around with a friend. She hums the part she was singing earlier and can’t resist a little accompanying dance.

When asked where she sees herself in five years, Maral says: “Rebuilding Syria. With cricket, with music and dancing, and with love.”