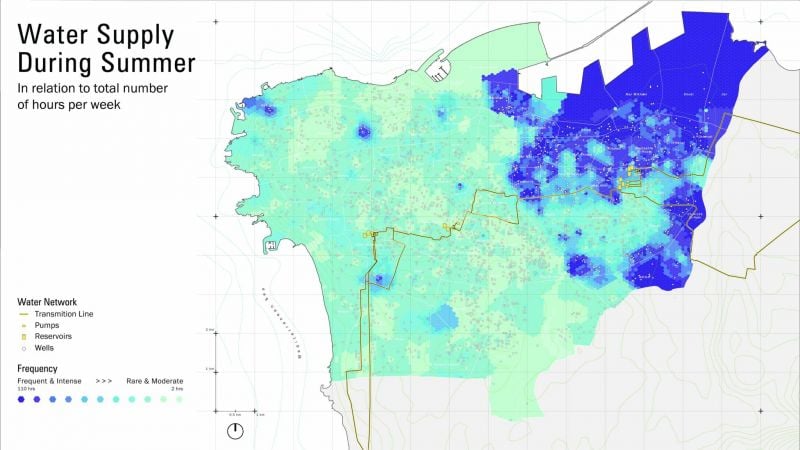

The frequency of water supply per week in different quarters of Beirut. 2022, Courtesy of Beirut Urban Lab.

BEIRUT — For 26-year-old Farah Baba, Beirut’s worsening water shortages have become an increasing drain on her time and energy. The communications officer with an NGO, who lives with her parents in Hamra, had already gotten used to regular cuts to the public water supply.

Since the building does not have a well, her family would buy privately-supplied water from a roving truck when the public water ran dry, but even that is not an easy alternative anymore.

Because of the economic crisis, Baba said, not everyone in the building can pay, making the truck driver less inclined to pass by in order to save on fuel, the price of which has also skyrocketed in recent months.

“So sometimes the process is delayed because the water tank guy won’t come to fill the water just for a few houses since also he would be spending his gasoline on the way and not making much profit,” she said. “On average, every seven to 10 days the water is completely gone.”

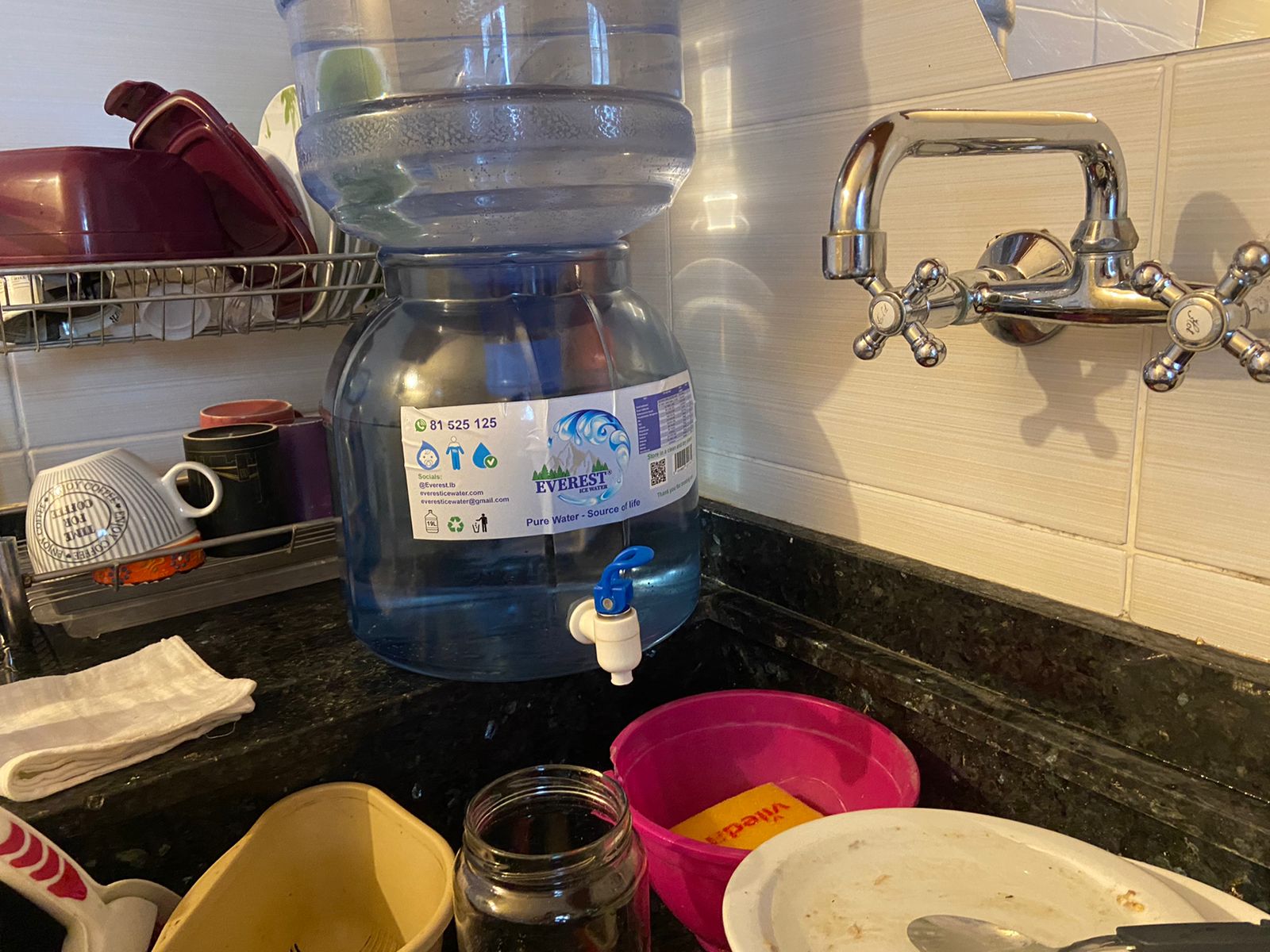

Farah’s water dispenser, which she uses as a makeshift faucet to wash her dishes in lieu of running water. (Photo courtesy of Farah Baba)

Farah’s water dispenser, which she uses as a makeshift faucet to wash her dishes in lieu of running water. (Photo courtesy of Farah Baba)

To cope with the shortages, Baba’s family is now resorting to hauling up large bottles of store-bought water to drink and for household tasks.

“A lot of the time, I or the water guy or my mom have to drag it up the stairs, and we’re using buckets just like old times whenever we want to shower or wash our hands,” she said.

Meanwhile, in the neighborhood of Sodeco in Achrafieh, Hiba Hammoud, 28, a computer scientist, said she still has 24/7 water access.

“Sometimes the water pressure is light, but generally it's never gone,” she said.

Different reservoirs for different parts of the city

Every year, the lion’s share of complaints about water come from the western side of the capital.

Abir Zaatari, a researcher at the Beirut Urban Lab at the American University of Beirut, is part of a team of researchers who found that certain quarters (Rmeil, Medawar, Saifi and Achrafieh) receive public water abundantly while Ras Beirut, Bashoura, Mousaitbeh, Ain al-Mreisseh and Mazraa suffer from public water scarcity.

The research was conducted as part of the 2018 Beirut Built Environment study, which showed acute imbalances in how water is supplied in Beirut.

“We found that 30 percent of the buildings in [the] eastern region receive [public] water less than three times a week in summer, while in the other area, we found that 87 percent of the buildings receive water less than three times a week in summer,” Zaatari said, showing “a significant difference.”

In winter, she said, eight percent of the surveyed buildings received public water less than three times a week in “east” Beirut, while 60 percent of those in “west” Beirut received it less than three times a week.

A shallow reading of these numbers would indicate an east/west divide in the level of services, possibly even a sectarian one following the boundaries of the city’s different neighborhoods.

However, Zaatari said that the issue has more to do with topography and infrastructure than it does with sectarian or political divides.

“Beirut is a topographical city and water distribution reservoirs are located on top of Beirut’s three hills: the Achrafieh hill, the Tallet al-Khayat hill and the Burj Abi Haidar hill,” while the city’s two water reservoirs are located in Achrafieh and Tallet al-Khayat.

Each reservoir receives water from a different treatment plant, Naameh in the case of Tallet al-Khayat reservoir and Dbayeh in the case of Achrafieh, “and service exclusively households in surrounding neighborhoods with lower altitudes” she said, such as Hamra or Mar Mikhael.

Zaatari said that Ashrafieh receives water from the treatment plant in Dbayeh, which gets its water from the Jeita streams and other wells. Tallet al-Khayat, on the other hand, receives water from Naameh, which only relies on streams and no other source of water supply.

From the Ashrafieh reservoir, water flows to the surrounding neighborhoods of eastern Beirut such as Gemmayzeh, Mar Mikhael and others, while the Tallet al-Khayat one flows into western neighborhoods, including Hamra and Qoreitem.

Abundance or scarcity in the water supply is entirely linked to how much water is received from each of the Dabyeh and Naameh water treatment plants.

Zaatari noted that earlier studies showed that Dbayeh treatment plant receives water from Jeita streams and provides up to 77 percent of the city’s water needs, while Naameh water treatment plant can only provide up to 23 percent of the city’s water needs.

Zaatari said the Naameh plant cannot service a heavily populated segment of the city on its own.

“The topographical layout of the city and the location of the reservoirs and from where water is channeled from, have really affected this divide in the water supply,” she said.

Zaatari also said there are severe infrastructural issues that weaken the water system in all corners of the city.

“We cannot dismiss the fact that the water system and infrastructure and its lack of maintenance have actually contributed to extreme leakage in the system,” she said, which leads to a staggering 45 percent water loss from distribution leaks.

“So basically, it's a combination of topography, the location of the water reservoirs, the poor maintenance of the water infrastructure, and, of course, poor governance of water systems.”

DIY fixes

Jean Gebran is the General Director of the Beirut and Mount Lebanon Water Establishment, the body in charge of managing the water supply in the capital. Speaking to L’Orient Today, he attributed the water issues to the lack of electricity needed to pump the water. Any solutions to the crisis would require fixing the electricity shortage, he said adding that the Dbayeh station cannot provide water for the rest of the city.

For buildings that have their own wells, the shortages have been less severe, which Zaatari said shows excessive reliance on informal sources of water in water-scarce neighborhoods.

A whopping 76 percent of buildings built after 1996 have dug wells and are particularly concentrated in neighborhoods with low public water supply.

Zaatari noted that these solutions are ecologically unsustainable as they deplete the underground water in the city. They also pose a health hazard to city dwellers due to the wells’ contamination with E. coli and other pollutants.

In the water sector, as in the case of private generators in the electricity sector, the DIY fixes to fill gaps in state services are insufficient to meet people’s everyday needs, but also have negative effects on the environment, research has found.

According to a 2022 study, both trucked and pumped well water weigh heavily on the environment. The research found that the biggest energy consumption in the water sector in Beirut came from these two sources, in total accounting for 83 percent of the sector’s energy consumption and 72 percent of its carbon emissions, but only supplying 23 percent of its needs.