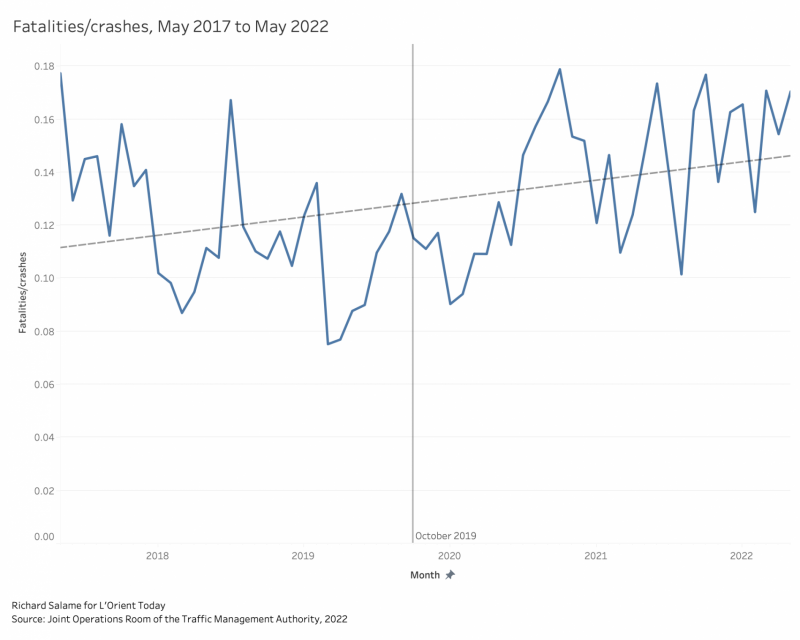

A graph detailing the number of fatalities per crash since May 2017. (Credit: Richard Salame/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — More than 1,350 people have been killed in traffic crashes since April 2019, L’Orient Today has learned via a records request. An additional 13,800 people were injured during the same time period in more than 10,000 reported crashes.

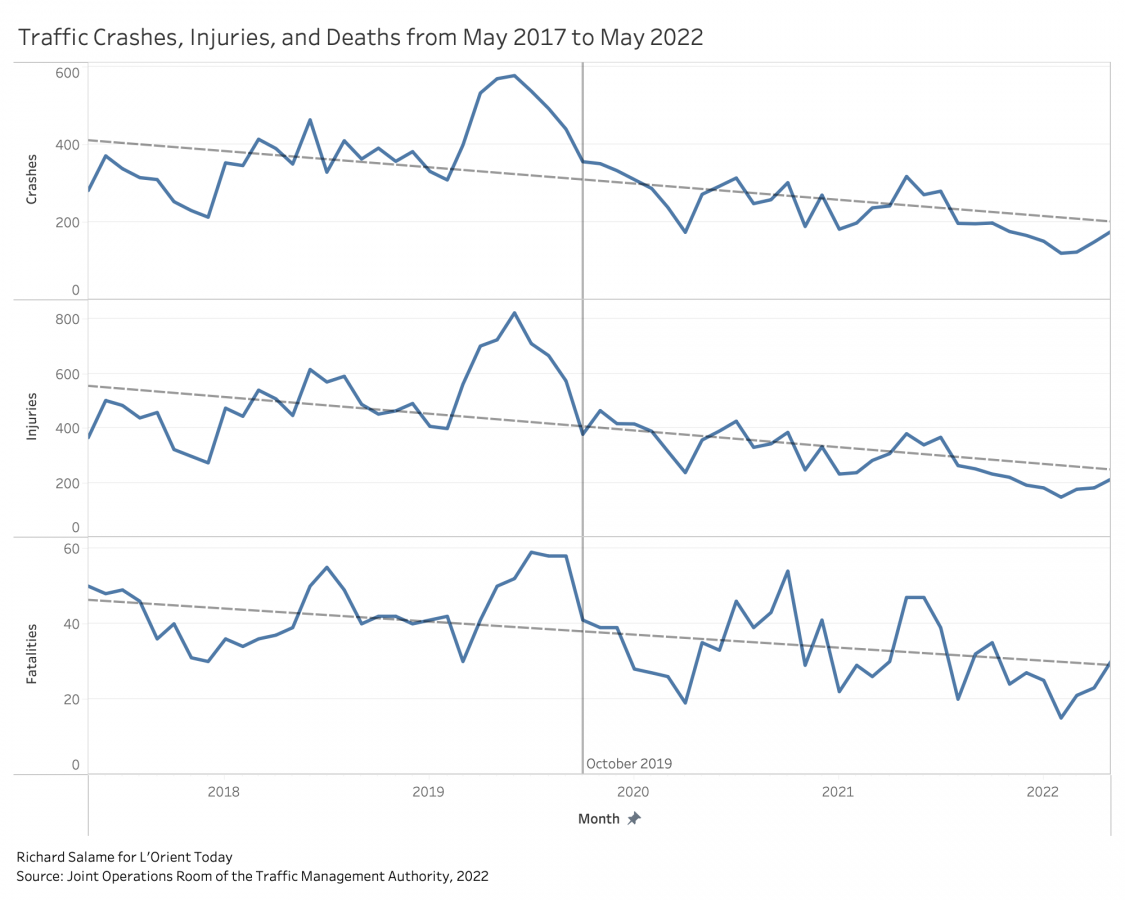

The data suggest a trend downwards in the number of crashes and deaths over the last five years, especially noteworthy since the beginning of the country’s economic and social crisis in October 2019. In the 32 months from October 2019 to May 2022, Lebanon witnessed an average of 237 crashes per month, compared to 373 crashes per month in the 32 months leading up to October 2019. An average of 32 people were killed per month in the crisis period, compared to 43 per month pre crisis.

A graph detailing the number of crashes, injuries, and fatalities since May 2017. (Credit: Richard Salame/L'Orient Today)

A graph detailing the number of crashes, injuries, and fatalities since May 2017. (Credit: Richard Salame/L'Orient Today)

These data from the Joint Operations Room of the Traffic Management Authority are “approximate and not final,” according to an official with the Authority, but they give the most up to date picture of death and injury on the country’s roads so far.

The lower number of crashes appears to be in spite of a marked decrease in the amount of street lighting and traffic lights and a drop in both road work and car maintenance as both the governments and drivers find themselves unable to afford repairs. At the same time, the fuel crisis and rising cost of gasoline and diesel is widely said to have caused a decrease in the number of cars on the road, which may be a factor in the lower number of crashes.

On the other hand, the crashes that do occur have become more deadly. With the average monthly ratio of deaths to crashes rising from 0.12 deaths per crash to 0.14, leading to an excess of roughly 120 additional deaths compared to if the lethality of crashes had stayed constant.

Transportation expert Tammam Nakkash noted that globally, during the COVID pandemic, lower traffic volumes have translated into increased fatalities in a number of countries, as the cars on the road drive faster than they were able to before.

In crisis-afflicted Lebanon, with gas prices pushing many out of their cars, a similar phenomenon might be at play.

“If you walk around the city now, in Beirut, you find out how much more difficult it is now to walk. First of all because the traffic signals are not working,” Nakkash said. “Due to lower traffic there are higher speeds on the city streets and this is making walking even more dangerous, plus, of course, the condition of the sidewalks.”

“Everything that falls under the rights of pedestrians is not respected,” said Ziad Akl, founder of traffic safety organization YASA.

Traffic crashes are a leading cause of death around the world, killing 1.35 million people annually and injuring 50 million. They are the leading cause of death for people aged 5-29 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Incidents on the road that kill or maim people are often referred to as “accidents,” but choices in vehicle design, traffic engineering, and city planning lead to well-known and predictable rates of death and injury, which disproportionately fall on cyclists and pedestrians. Unlike many other preventable causes of death, the victims of traffic crashes are overwhelmingly healthy up until the moment of the incident.

The ongoing tragedy is particularly glaring in Lebanon, whose safety record is “among the worst globally,” according to the World Bank. Traffic incidents are the number one cause of unintentional injury and death in the country.

“Honestly the status of roads in Lebanon is very dangerous, especially with the increase in the number of pits and potholes,” said Akl.

Due to the economic crisis, Akl believes Lebanon’s roads have become much more dangerous, despite the fact that total accidents have trended downwards. While the skyrocketing cost of gasoline has caused a reduction in the number of vehicles on the road, Akl points to the loss of streetlights, the increase in potholes and the inability of the government to afford maintenance. To help fill in the literal and metaphorical gaps left by the state, YASA has been replacing manhole covers on the highways.

From 2007 until the start of 2022, an average of 4,259 accidents were reported each year in Lebanon, killing an average of 519 people and injuring 5,760 annually.

This is likely an undercount, given that the WHO has found that Lebanese death registration data is not “at least 80 percent complete” and has, in the recent past, estimated a traffic death rate nearly double the rate reported by the state. The World Bank has also deemed these figures “underreported.”

Most victims of traffic injuries in Lebanon are men, with the largest number of injuries happening to people between the ages of 15 and 29, according to a 2021 study by researchers at the American University of Beirut, Lebanese University, and two US universities. Nearly 40 percent of people injured on Lebanon’s road are motorcyclists. According to the study a quarter of all people injured in traffic are pedestrians. The WHO has estimated they make up almost 40 percent of traffic deaths in Lebanon. Poor and low-income people are disproportionately impacted by road safety, according to the World Bank.

What is being done?

Lebanon does not lack traffic laws. It is illegal to use a cellphone with or without hands while driving, drunk driving is illegal, the default urban speed limit is 50 km/h, seatbelts are mandatory, motorcyclists must wear helmets, and small children must be in car seats.

But many of these rules are often flouted, with dangerous effects. Illegal parking of cars and motorcycles on the sidewalk, for instance, forces pedestrians onto the street where they are liable to be hit by cars.

There are laws to protect both cyclists and pedestrians, Elena Haddad of mobility justice organization Chain Effect said, but “there’s no awareness. They’re not implemented and there’s no respect at all for [the laws].”

The Internal Security Forces does not have a dedicated traffic enforcement department, something many police departments worldwide contain. Nakkash says this is because stakeholders have been unable to agree on which sect should be granted leadership of the new department. An ISF spokesperson could not be reached for comment.

But law enforcement isn’t the only fix. Another aspect of road safety, especially for the most vulnerable road users, is building infrastructure that prioritizes them. Separating cars from cyclists and pedestrians protects them from being hit. Replacing intersections with roundabouts, reducing road widths, installing speed bumps and median islands, and extending the curb all reduce car speeds, which make crashes more survivable for the people outside the car.

These moves can also help change people’s perception of space and encourage alternative forms of mobility, Haddad points out. Chain Effect has held bike to work events during which they have marked out temporary bike lanes with cones, which made participants feel safer and, therefore, more willing to participate. Infrastructure can encourage “a paradigm shift,” she said. It can make people “feel more confident and safe to commute.” But, she warns, “There is no use for infrastructure without proper governance and maintenance.”

Nakkash, a former member of the Lebanese Traffic Safety Committee chaired by the Minister of the Interior, says traffic safety is not prioritized by the government.

Under the new traffic law adopted in 2012, Lebanon has a National Road Safety Council, headed by the Prime Minister, which is supposed to meet every three months and issue an annual report to the media on its activities. The council’s Twitter account has posted just twice since February 2020, while its Facebook account hasn’t posted at all since March 2020. A spokesperson for the prime minister’s office did not respond to a request to view the council’s latest annual report.

In addition to the Council there is the Traffic Safety Committee, which Nakkash says is more active. But even the committee is not used to its full potential.

“We rarely have met with a [Interior] minister more than three times,” recalls Nakkash. The committee’s secretary general regularly pleads with the Interior Minister to convene meetings of the committee, which he does not do, Nakkash says, and the secretariat doesn’t receive the budget, staff, or ministerial support needed to do effective work. An Interior Ministry spokesperson could not immediately comment on the matter.

“Traffic safety is not taken seriously in Lebanon, basically,” said Akl. “In the past there were more serious efforts but now we are faced with almost complete paralysis.” He pointed to the “unjustified” suspension of mechanical inspections. Without inspections we are unable to confirm that the cars we allow on our streets are road-worthy, he says.

Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi suspended mechanical inspections of cars in May.

In the long run, experts say improving traffic safety will require changes to infrastructure, enforcement, vehicle standards, and driver education. Lebanon is currently five years into a six-year, $200 million World Bank-funded road rehabilitation project that aims, among other goals, to reduce traffic fatalities by 15 percent on five priority road sections. Of that, $2 million is earmarked to support the Traffic Safety Committee’s secretariat. Despite the many crises facing Lebanon, that work seems to be continuing: last month the World Bank contracted a traffic safety consultant on an 11-month agreement.