Illustration by Mark Mansour

With the economic crisis and the rapid depreciation of the Lebanese lira, the salaries of civil servants have melted away, leading to dramatic lifestyle changes for a majority of them.

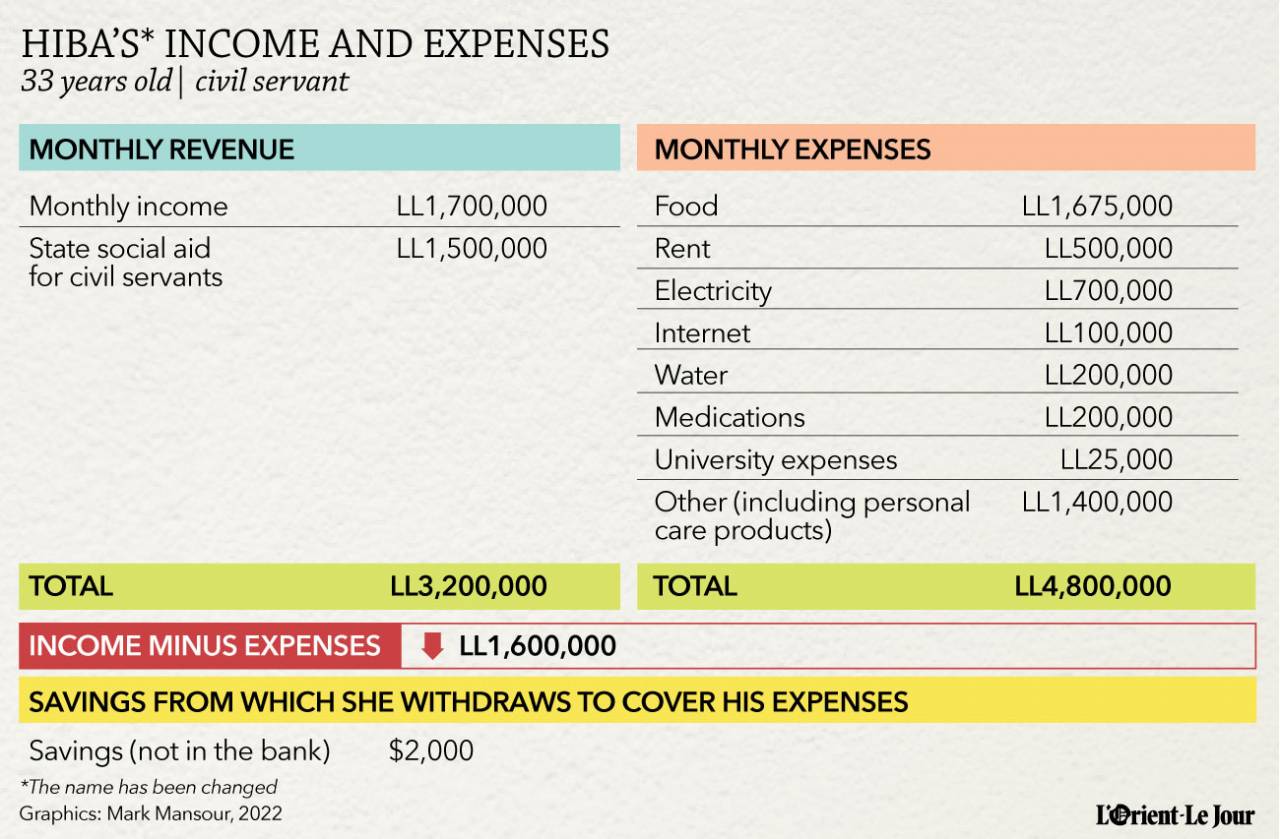

“I'm in survival mode, not life mode,” says Hiba*, 33, who works in a public administration in Tripoli. She earns LL1.7 million net (after taxes), along with a transportation allowance that should be LL64,000 per day. The government has not paid this allowance since February, Hiba says. Nevertheless, she receives an additional monthly stipend from the government of LL1.5 million per month. But even with this aid, her salary, which was worth $1,133 (not including the transport allowance of LL8,000 a day) before the crisis, has dropped to $100.

She finds this situation hard to stomach. But what is even more difficult for a woman who studied law at the Lebanese University and “fought” to pass the bar exam in 2015, is to see colleagues accepting — or even asking — for bribes. Still, she says she “understands” those who have steep transportation costs or children “and have no other choice to survive.”

In her misfortune, however, Hiba considers herself lucky. By “pure chance" she lives close to her work and can walk to it, which is not the case for most of her colleagues. Moreover, her monthly rent of LL500,000 has remained unchanged, even amid the crisis.

“I must be the only one in Lebanon who still pays such [low] rent,” concedes Hiba, who says she has a “kind and understanding landlord.”

As for her generator, she pays LL700,000 per month for a 3-ampere subscription that allows her to light a lamp and her internet router. Hiba’s Ogero bill, before the July increase, was still LL100,000 a month. Her TV stays off and she hasn't had a cable subscription for over a year. The only activity she allows herself in order to “move forward in life and to continue learning” is her distance learning classes in literature at the Lebanese University, which cost her LL300,000 a year. She spends the rest of her free time watching videos on her phone.

Her salary and the state aid barely cover her living expenses, medical costs and food. She only eats potatoes, bread, laban (yogurt) and the occasional egg.

“I've gone two Ramadans without meat,” she says. To make ends meet, she has resigned herself to selling some of her furniture. Her water heater no longer works and the kitchen sink is broken, but she can't fix them. So she does the dishes in the bathroom sink. “It's not hygienic, but I have no choice,” she says.

Before the crisis, her friends, many of them lawyers, spent long evenings at her home. Today, she is ashamed to receive anyone. The crisis has made her “antisocial,” she says. “My house has become my prison.”

Unfortunately, Hiba cannot count on her parents, who are both divorced and remarried, and are also suffering from financial difficulties. To make ends meet, she is dipping into the $8,000 she saved before the crisis to buy a car, of which she has barely $2,000 left.

Today, she spends this money on a few hygiene products and oil for frying food.

“I'm over 30 years old and I couldn't even buy a car,” she says.

The future, she believes, does not look promising for her; starting with the reforms demanded by the International Monetary Fund, which include a reduction in the number of civil servants. She thinks that this measure makes sense: “The public sector must be swept from top to bottom.”

But she is worried: “I know that those who are going to keep their jobs are those who are well-connected,” which is not the case for her.

In this context, is leaving Lebanon an option?

“I studied Lebanese law. If I leave, I would have to start all over again! Not to mention the fact that I can't even afford a visa.”

* First name has been changed

This article was originally published in French at L'Orient-Le Jour.