Illustration by Mark Mansour

On Aug. 1, 2020, Imad received an email informing him that the bank where he worked — which, like the rest of the Lebanese banking sector, had been plunged into an economic and financial crisis since the previous summer — was looking to reduce its workforce. Anyone willing to make a voluntary early retirement would be compensated. Imad was the manager of a branch in Shehim, in the Chouf, after 36 years of climbing the career ladder within the institution.

"I had only six months left to work before I reached the legal retirement age, and their offer was interesting, so I jumped at it," he says. In addition to getting a "fair" compensation equivalent to six months' salary, he and his family would be given insurance for the following year and access to benefits normally reserved for bank employees, including the possibility of converting the compensation he would receive into dollars at the rate of LL1,500 to the dollar, before withdrawing them in lira again at a higher exchange rate (first LL3,900 and then LL8,000 to the dollar) – enough to make a nice capital gain.

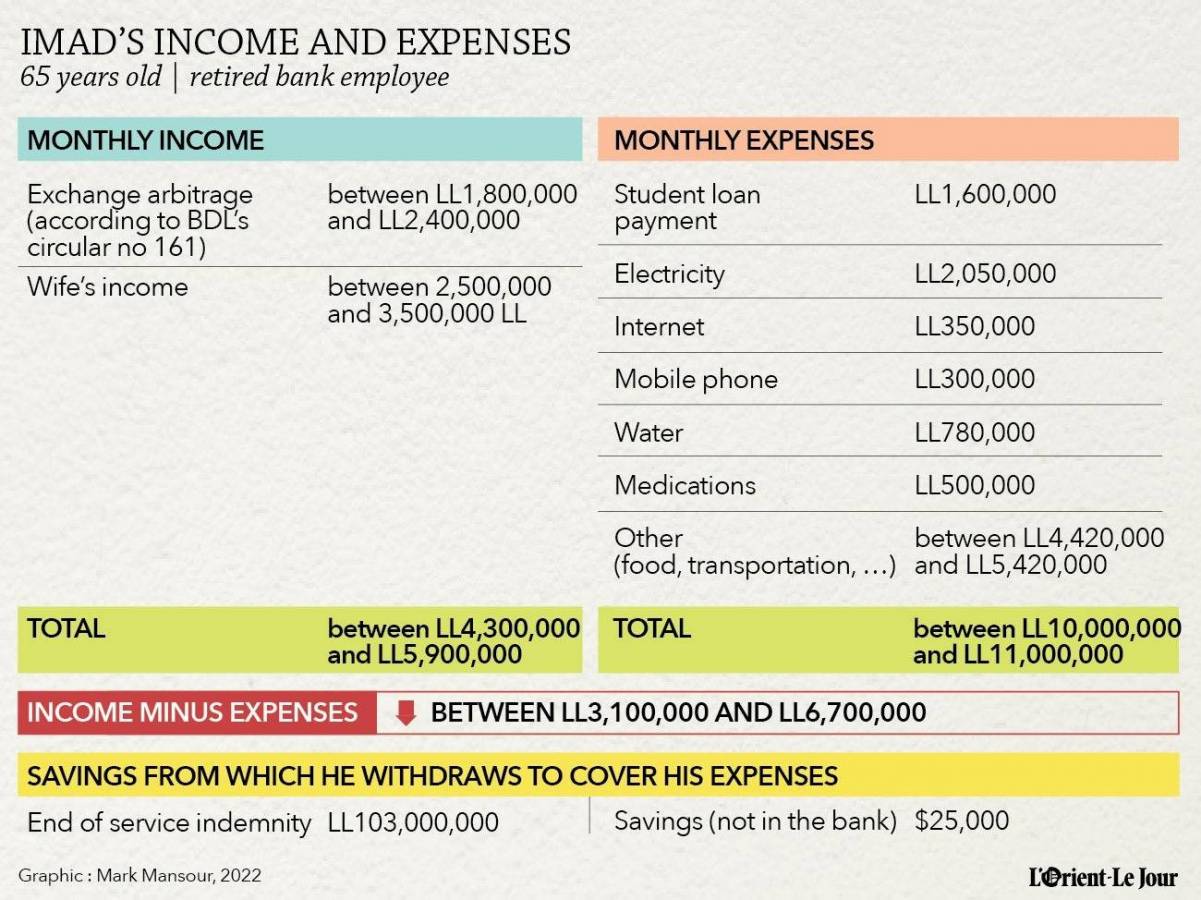

He would use this mechanism to convert his end-of-service indemnity into dollars. Having already withdrawn part of it after 20 years of service, as allowed by the Lebanese labor code, Imad was only entitled to LL103 million. While this amount was worth some $68,000 at the official rate, it is now worth a bit more than $3,200 at the parallel market rate of more than LL32,000 to the dollar, a discount of about 95 percent. But thanks to the system he benefits from, Imad manages to withdraw his money with a discount of closer to 75 percent.

Savings, antiques and land

Given the levels of depreciation and inflation, Imad is aware that this stash of funds will not last long.

"Every penny counts," he says, but "thank God, our situation is much better than that of the vast majority of Lebanese.”

Forced to adapt to this new reality, the 65-year-old has reviewed his spending habits. Between the explosion of the cost of a generator subscription (between LL1.5 and 2 million per month for five amperes), the repayment of a loan for his youngest child's schooling (LL1.6 million per month) or the recent increases in telephone (LL300,000 per month) and internet (LL350,000 per month) bills decreed by the Ministry of Telecommunications, the monthly expenses are getting heavier.

"Fortunately, my wife provides some income through her part-time job as an accountant," he says. The problem is also that, amid a changing crisis, he can no longer calculate an accurate monthly budget. According to him, the monthly household expenses are now around LL10 to 11 million.

He is doing everything possible to adapt: canceling health and car insurance, cutting back on travel and reducing the amount of food he buys.

"We used to have a barbecue at home every Sunday, for example. That is now out of the question. We can only afford it once a month, and even then we have reduced the amount of food we prepare," Imad continues. On the other hand, "there is no question of skimping on medication, especially not for high blood pressure. My father, not having stayed on top of it, died of its consequences. I will not repeat the same mistake.”

To make ends meet, the former banker also relies on a legal and limited arbitration mechanism, thanks to which he can convert, each month, a certain amount of Lebanese pounds into dollars in banks at the Sayrafa rate and then resell these currencies on the parallel market at a higher rate.

"This kind of operation has allowed us to profit from some two million additional lira, depending on the difference between the two rates," he says.

Imad can also count on $25,000 in savings, accumulated during his career, and stored securely at home. Passionate about antiques, he also says he is ready to sell part, or even all, of his collection, if necessary. And then, "if it has to be done, I will sell one or more of the three parcels of land I bought for my children. But we are not there yet," he says. His tone makes clear that he is dreading that day.

This article was originally published in French at L'Orient-Le Jour.