The AIF preservation team at work. (Credit: Blanche Eid / AIF)

BEIRUT — It’s a bit stuffy at the offices of the Arab Image Foundation on this particular afternoon. Like many places in Beirut these days, the converted flat on Gemmayzeh’s Rue Gouraud lacks the crisp frigidity of air conditioning, and all the windows are shrouded in layers of plastic sheeting.

“We had to put up the vinyl when the port silos caught fire,” AIF director Heba Hage-Felder shrugs. “As a precaution.”

The rooms are in meticulous order. It’s quite unlike the scene in August 2020, when the Beirut port blast tore through AIF, collapsing walls, herniating ceilings and pitching swirls of flotsam over the floors.

Hage-Felder opens a door and a gust of cool air spills out. The preservation and digitization work rooms — the heart of which is the cool storage unit, and its archive of delicate film and glass plate images, as well as the digital server — demand a climate-controlled environment year-round. This is a challenge given scarce state utilities and soaring diesel and generator costs to keep the power running.

Back in her office, three historic, blast-damaged portraits look on and the blades of a large fan whirr as Hage-Felder reflects upon her two years at the helm of AIF.

“We have a huge operational budget,” she says. “It’s not only about running programs that you can minimize or maximize. It's about ‘How do we maintain the safe climate the cool storage room requires?’ That's why we're probably one of the first cultural institutions in the city to be autonomous with solar energy for the storage room and the two labs.

“That’s why you’re sitting in a room that has no AC.” She grabs a handful of humid air. “Whatever amperes we have from our solar panels safeguard the lab and the cool storage room. Ideally, we’d be running the entire premises on solar, to reduce our long-term running costs, but there’s only so much one can take on before being hit by another set of demands.”

The AIF team poses for a team photo beneath the foundation’s recently installed solar panels. (Credit: Christopher Baaklini / AIF)

The AIF team poses for a team photo beneath the foundation’s recently installed solar panels. (Credit: Christopher Baaklini / AIF)

‘Agility is a double-edged sword’

Earlier this summer AIF announced it was in the market for a new director. Hage-Felder will depart the job but not the institution. She will turn her attention to her family’s collection of documents from Ghana and Lebanon, which she deposited at AIF in 2002.

When she left her previous job at the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, a Beirut-based foundation that supports Arab artists, “the idea was to plunge into my own practice,” she recalls, bemused. When artist and AIF BoD chair Vartan Avakian approached her about the job at AIF, she says, “it was a very odd moment.”

As AIF was getting its start 25 years ago, Hage-Felder explains, its founders shared a converted residential space with Mada, an NGO Hage-Felder was setting up.

“The two [organizations] started at the same time, sitting in two corners of one apartment. Then 23 years later somebody [from AIF] comes to me and says, ‘Would you be interested in applying?’ I don’t regret the decision.”

Amid Lebanon’s current cycle of crises, the AIF is celebrating its 25th anniversary.

The nonprofit’s collection of over 500,000 photographs and documents was amassed through the work of artists and scholars as well as donations. AIF’s origins as an artist-led enterprise have helped shape its archival approach. Its object, as its 2009 mission statement phrases it, has been to “collect, rethink, preserve, activate and understand the photographs through their multiple strata, and enrich the collection in the process.”

There’s a lot to unpack about AIF, Hage-Felder says.

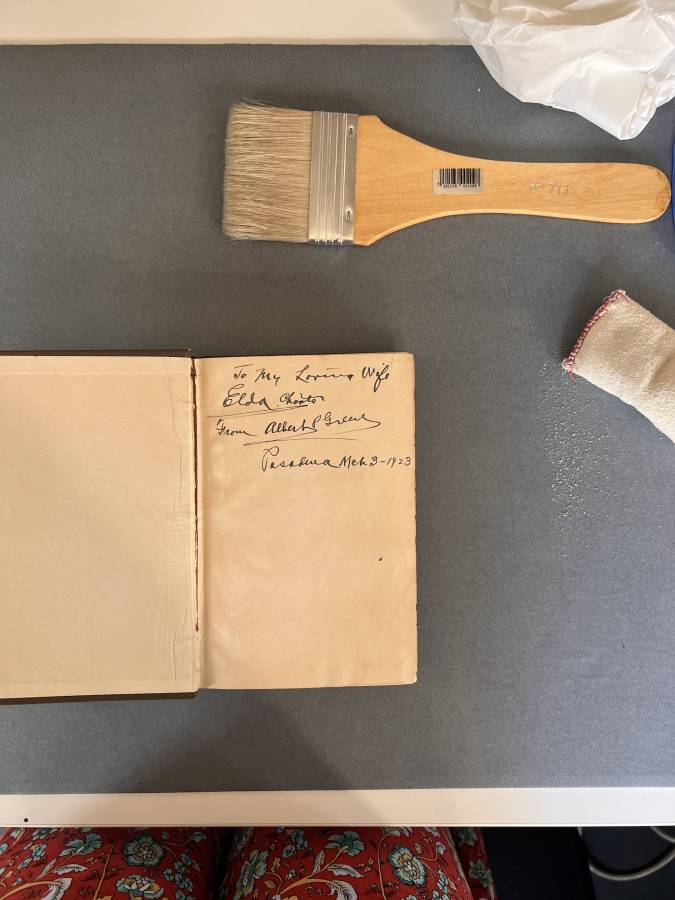

An AIF document in the midst of conservation. (Credit: Heba Hage-Felder / AIF)

An AIF document in the midst of conservation. (Credit: Heba Hage-Felder / AIF)

“This very small institution has been carefully built, folded and molded with love,” she muses, “and conflict. We don’t have a government telling us what to do. We’re not a national institution. We’re not a typical museum or a typical archive. This agility is a double-edged sword: It gives us flexibility but it puts incredible responsibility on us to be accountable for what we say in our mandate and how we do things — how we collect, how we respect the rights of collection holders.”

Copyright issues, for instance, must be balanced with giving artists and researchers access to the collections, while sometimes educating users on what it means to put an image in an artwork and then sell it.

Daunting challenges

The past two years have done nothing to make running AIF any easier.

“I plan with three scenarios in my head, and it can go either way,” Hage-Felder smiles. “People laugh. If you’re doing good practice, you do risk analysis maybe once a year. Here, we do it every week. We don’t even know if the banks will open by Thursday,” a nod to the bank strike that started the day of her interview with L’Orient Today. “You form a second skin. Then you have moments where you zoom out of everything and think, ‘What is this that we're doing? Why is it relevant?’

Like all Lebanon’s arts institutions, brain drain has hit AIF.

“Looking after the team, trying to build opportunities and their capacities and maximizing whatever anyone can offer — it’s something I would do as director anyway, but in Lebanon these days, you know you may not have the impact that you normally aspire to.” A scarcity of skills has also hampered AIF’s ambitions to develop various facets of its digital platform.

“We put out the profile for creative technologist twice, and couldn't get people. It’s understandable. Anyone trying to get their career going is just thinking ‘How do I get myself out of here?’”

Retaining institutional memory, the continuity that’s lost when brain-drain robs an organization of its experienced personnel, has dogged Hage-Felder’s work since taking the helm of AIF.

Another major challenge confronting AIF is its dependence upon donations.

The AIF preservation team at work. (Credit: Blanche Eid / AIF)

The AIF preservation team at work. (Credit: Blanche Eid / AIF)

“The first thing we focused on right after the [Aug. 4] disaster — knowing this is the time when people are going to be attentive to everything going on in Beirut — was engaging with donors.” The hope was that donors would see AIF both through its emergency response and its recovery.

“Donors are not there yet, but we've been lucky with the ones that know the foundation, and also some new ones that have come on board … the Getty Foundation and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Beirut have been the two most-generous donors — not only in the money but also in the way that they’ve shaped the funding so that it remains flexible.”

Hage-Felder says the Lebanon Solidarity Fund, organized by AFAC and Al Mawred in the wake of Lebanon’s economic collapse, was incredibly important, not because of the sums disbursed but because the assistance arrived at a time of critical need. Individual donors are also instrumental.

“We’ve had one or two recurring donors, either people who have been part of the foundation or who are from the region, who have been with us through thick and thin. One is local, but she’s from the diaspora, a profound admirer of the foundation, who herself understands archiving. [Contemporary artist and AIF co-founder] Akram Zaatari has benefited a lot from the foundation and is a very generous contributor as well.”

‘Limitless possibilities’

Hage-Felder is still struck by what she terms the “limitless possibilities” of AIF’s collections.

“There probably aren't any independent structures of our size who have custodianship over so many collections from across this region,” she says. AIF currently holds around 315 collections — about half a million photographic objects — and that number is rising, she says, but it’s not about the numbers.

“The ‘Arab’ in the Arab Image Foundation is a geographic denomination, not an ethnic [or otherwise] exclusive term. We have a lot of Armenian collections, for instance, and researchers can activate work around that collection. We don't have any collections from Iraqi Kurdistan, so there is an incentive to fill in these gaps and to try and see how we can be more inclusive within our own collecting practices.”

One of the blast-damaged portraits in the AIF offices, ‘Studio portrait of a naked woman’ taken by Armand in Cairo between 1945 and 1950. Gelatin silver printing-out paper print, Armand Collection. (Courtesy of AIF)

One of the blast-damaged portraits in the AIF offices, ‘Studio portrait of a naked woman’ taken by Armand in Cairo between 1945 and 1950. Gelatin silver printing-out paper print, Armand Collection. (Courtesy of AIF)

AIF has also worked to archive queer stories, as mainstream depictions of queer culture “can be extremely sensationalist,” she says.

“As important as it was to talk about it in many mediums, our interest has always been in how to do this with sensitivity. How do we bring the people who are from this community to be the owners of their own story?”

Hage-Felder nods to AIF’s work with photographer and artist Mohamad Abdouni on “Treat Me Like Your Mother,” a public archive of studio shoots, interviews, personal photos and archival imagery documenting the stories of 10 trans women living in Beirut.

“We are custodians of probably the only queer collection in the Middle East today,” Hage-Felder says. “They’re little steps, but I think that what we've tried to do over these two years should continue, regardless of who’s at the helm.”

AIF has been seeking a new home for seven years now, a hunt that the Aug. 2020 disaster only accentuated. For two years Hage-Felder has been searching for a location that will allow AIF to cohabitate with other cultural organizations. Negotiating with landlords, who assume that a nonprofit operating on international donations controls vast resources, she says, has been ruthless.

“It is incredibly exhausting, dealing with landlords, trying to make sense out of their logic,” she says. “Two years later, we’ve come back to the place we started, except that more than half the population [is now poorer than they were], while landlords still believe that real estate is untouchable. We’ve looked at more than 14 places. We even had a committee so that it’s not a one-person decision, always with the mindset of looking for a place that we can share with others.

“We will relocate,” she smiles. “That’s all I can say.”