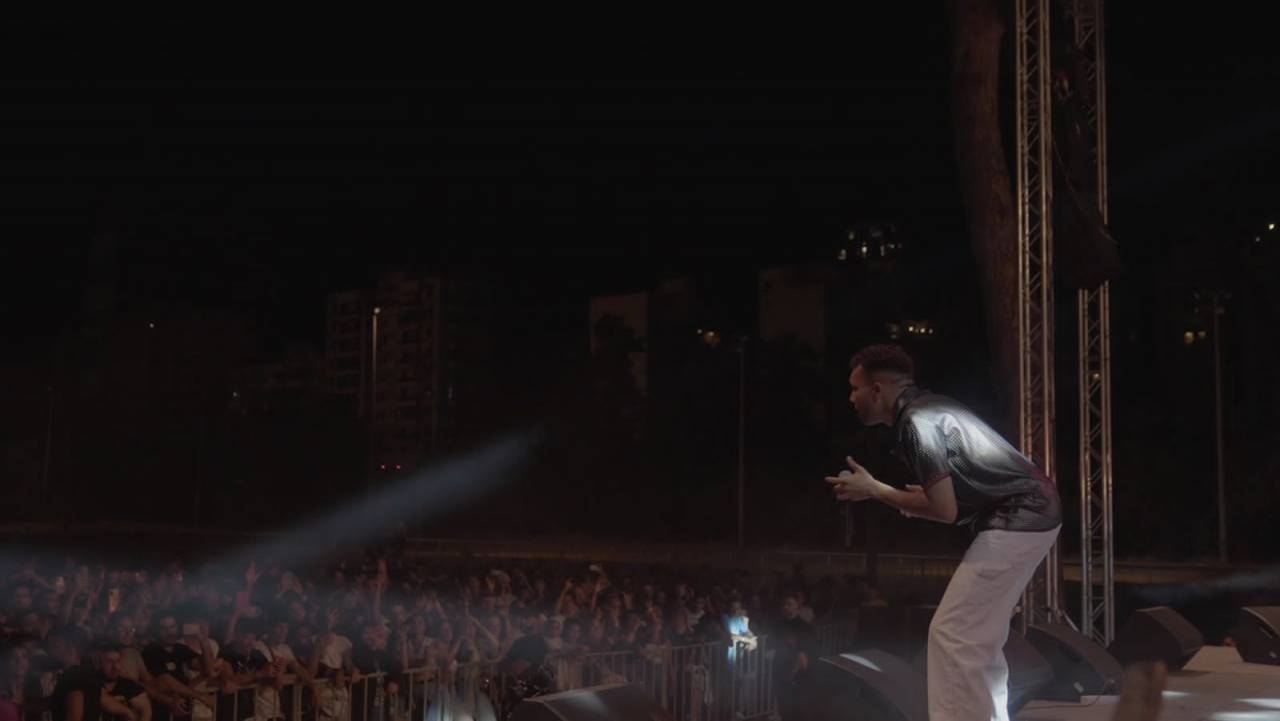

Omar Dafencii performs live for the first time at AFAC's 15-year anniversary concert. (Credit: Ahmad Chehadeh)

BEIRUT — Among the tall pine trees and relative calm of nature around Beirut’s Hippodrome in its Corniche al-Mazraa area, a large crowd eagerly awaits, with heads pointed toward the stage. It’s dusk when the concert starts. First up, Omar Dafencii, a Sudanese-Saudi rapper with a smooth flow of words.

Dafencii has garnered a large audience since he began releasing his songs in 2021, and his recent song, King AlHalba, or King of the Ring, garnered more than 7.7 million views on Youtube. The song, produced by Palestinian producer Khayyat, plays a smooth trap beat with drums and bass, layered with keys that add an extra emphasis.

“Do you guys know that this is my first performance — ever?” The crowd cheers in encouragement.

Though he’s released tracks for more than a year, he’s only shared his music digitally, through online music platforms and Youtube. Today, for the first time, he’s performing in person.

“I’m really happy, and I can’t explain how much joy I have right now. I hope you’re all happy?” Dafencii screams as the crowd roars in response. “Let’s get it.”

The bass drops.

Dafencii starts his performance as people dance and bob their heads to the deep bass echoing through the pine trees. The crowd is varied, with music enthusiasts from all backgrounds, families and their kids, and various fans from around the Middle East and North Africa region, represented by occasional sightings of Egyptian, Algerian, Tunisian and Palestinian flags. Some jump and dance while others inch closer to the stage, trying to get the right picture. In the distance, groups of people sit on the grass, sipping beer and enjoying the music.

Occasionally, there’s a faint funky smell in the air.

Artists from around the region came together on Saturday at Beirut’s Hippodrome, representing various styles of music, primarily from rap and hip-hop, but also including pop, afro beats and electro, as part of Midane, the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC)’s 15-year anniversary celebration. The lineup featured a wide range of musicians, including Sudanese-Saudi rapper Dafencii; Egyptian singer Donia Wael; Tunisian rapper KTYB; Egyptian electronic shaabi producer El Waili (Kareem Gaber); Rapper El-Rass (Mazen El Sayed), Lebanon’s lyrical therapist; and Egyptian rapper and musician Wegz (Ahmed Ali).

Just before the concert, at a hotel nearby, two Egyptian artists who recently released an EP together — El Waili, a producer with distinctly unique sounding beats with a Mahraganat (festival) twist, and Donia Wael, a biology major turned musician with a silky voice — spoke to L’Orient Today ahead of both of their first performances in Lebanon.

El Waili, who started off by masking his face when playing his tracks, has been in the music scene for more than six years. And although he had been producing for a while, El Waili says, “I got motivated by the Egyptian scene, Marwan Pablote, Molotof, DJ Dotty and they opened my eyes that no, maybe the Egyptian people can listen to something like this. It broke a barrier within myself and I could do what I love.”

The beats and drops are instantly recognizable as El Waili based on his unique and distinct style.

El Waili’s tracks play on Egypt’s folk shaabi music, with a varied range of deep trap, trance and hip-hop.

As the only woman headline at the concert, Donia Wael explains how she’s had difficulties transitioning to music, adding, “There are a lot of challenges being a woman [in music] in Egypt. For example, there are always limitations; there are certain topics you can’t talk about. You have to take care of what you say."

When asked about her performance, Donia Wael says, “I’m a person who really enjoys nature and … I feel like it helps people connect more, in an environment like this with open air.”

Dafencii performs on stage at the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC)'s 15-year anniversary at the Beirut Hippodrome. (Credit: Ahmad Chehadeh)

Dafencii performs on stage at the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC)'s 15-year anniversary at the Beirut Hippodrome. (Credit: Ahmad Chehadeh)

Over the last 15 years, AFAC has supported the arts and culture scenes around the Middle East and North Africa region through its programs and grants, providing $32 million in funding in the region to support over 2,100 projects. AFAC supports organizations and artists across all spectrums, ranging from dance, to film to literature, theater, photography and music.

Some of the artists featured in the lineup have been recipients of AFAC support, like El Waili and Lebanon’s soul of rap El Rass, who received an AFAC music grant back in 2013.

The lead-up to AFAC’s 15-year anniversary concert was marked with controversy as the music publication Ma3azef, a former partner in organizing the event, was accused of staying silent and covering up the alleged sexual assault and drugging of a venue manager by two artists linked with the music magazine back at a 2019 event hosted by Barzakh, the Ballroom Blitz and Ma3azef.

Shortly after the news broke, AFAC cut ties with Ma3azef, releasing a statement that said, “In light of the accusations against the management of Ma3azef, and in line with our strong belief in the responsibility of all institutions/organizations/spaces to deal with any assault by first, protecting survivors, and second, holding aggressors accountable, we announce the immediate dissolution of the partnership with Ma3azef and the termination of any role Ma3azef may have in the organization of the event.”

AFAC’s wide-ranging programs help artists develop their styles, providing them with the space and confidence of an organization backing their project ideas.

“It’s really a question of how to position creative expression or artistic and cultural production at the core of big important questions,” says Rima Mismar, the executive director of AFAC. “But at the same time, open the space for others to participate to engage with, and this is how dialogue is started. And now, acceptance or our understanding of the things will build over time.”

In the case of El Rass, although he has been part of the dialogue for around 10 years, his songs became anthems to Lebanon’s October 2019 protest movement, with his tracks, “Ashhadou,” “Shoof” and “Al Nar” reflecting the frustration and rage of Lebanese from Akkar to Sour.

His performance was on-brand, with a heated entrance singing “Hela Hela, Hela Hela Ho” in a distorted version of the usual chant, causing echoes through the crowd of the protests’ ballad targeting Gebran Bassil, the Free Patriotic Movement’s leader and President Michel Aoun’s son-in-law, as well as Bassil’s mother.

His song from 2017, Ashhadou, still resonates today, and as the beat of the track starts during Saturday’s performance the crowd goes wild.

“There’s something for us in these streets we need to take

There’s something for us in these battles we need to take

There’s something for us besides the fear and the promises,

it’s not given, this is something we need to take.”

His words continue as El Rass points his microphone towards the audience and a combination of voices sing the lyrics back to him.

El Rass’ set featured two other rappers, Syrian-Filipino rapper Chyno and Lebanese rapper Ali Salloum, known for his viral comedic videos before kicking off his music career.

“Lebanese artists are similar in my opinion to Palestinian artists in the sense that what they’re going to rap about is about their what’s what they’re seeing day to day, politically, socially, economically,” says Danny Hajjar, a media relations professional and DJ who created Sa’alouni El Nas, a newsletter on music and stories from the region. “It is [explicitly] more political than other rap scenes.”

El Rass is one of many artists who has used his music and words to reveal inequities and injustices in his country throughout the years, particularly during the 2011 Arab Spring.

“In 2011, it was definitely hip hop, like in Tunisia, Egypt. Rap was way more political, way more explicit. Hip hop in the region went back to kind of the roots of what the genre is, it is inherently a protest genre. Right. It is a subversive genre. So you had guys in Tunisia like Balti who were, like, constantly calling out the regime,” he explains.

Egyptian rapper Wegz performs at the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC)'s 15-year anniversary concert. (Credit: Ahmad Chehadeh)

Egyptian rapper Wegz performs at the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC)'s 15-year anniversary concert. (Credit: Ahmad Chehadeh)

As the genre develops, though, some are unable to practice it in their own countries. Like in the case of Ramy Essam, who performed songs in Tahrir Square during the Egyptian revolution but was later exiled from Egypt after police arrested him and others associated with a 2018 song, leading to the death of one of the filmmakers who made the track’s music video.

AFAC’s movements have shaped and fostered many art scenes around the region, responding to specific country contexts, like when the organization started a Lebanon Solidarity Fund after the Aug. 4, 2020, Beirut explosion, which severely affected areas of the city in which many artists and creatives live and work.

One of the beneficiaries of this fund was the Beirut Synthesizer Center, founded by Bana Haffar, Elyse Tabet, Ziad Moukarzel and Hany Manja, which focuses on electronic and synth music, though it also provides workshops on music theory and music production and is hoping to open up the center for more disciplines aside from music, like dance, sound design, art and fashion.

“There weren’t really these kinds of spaces, ” says Ziad Moukarzel, “where someone can go to a place and sit and work on their music, for free or for a very small fee.”

The Beirut Synth Center along with other music centers like Onomatopoeia, provide spaces and resources for artists to explore their musical creativity and to experiment.

“We are interested in exploring what the scene is doing and that’s how you start to see projects that are not only like trying to break boundaries but to push boundaries,” says Mismar.

“Experimenting and pushing boundaries could be at any level.”

Although more and more spaces are popping up, experimenting with various forms of sound design and music, like a recent Ashkal Alwan show where two artists, Tarek Atoui and Eric La Casa, recorded Beirut’s harbor between Oct. 12 and Oct. 17, 2019, the experimental scene is nothing new in Lebanon.

“It's not new at all,” says Mismar, speaking to the work she’s done with AFAC since 2011.

One of the largest examples of this is Irtijal, an experimental music festival founded more than 20 years ago in Lebanon, which has celebrated various artists and highlighted different forms of music.

As the music scenes expand and different underground forms of music take center stage, AFAC is hoping to continue supporting the arts and culture while expanding its initiatives to take into account various important considerations.

“One of the main things that we're looking at is basically how to address the inequity and inequality in terms of opportunities across the region when it comes to funding,” says Mismar. “So accessibility is a big question, be it at the level of artists who have less opportunities, are less in the limelight, less experienced. But also at the level of the audience, [we are] asking ourselves how can we contribute to building channels for dissemination, distribution and circulation of works of arts and culture.”