Abou Sami (r), oldest of the guards in Halba, Akkar, with two of his comrades posted. Located at the entrance to Halba, this point is the most dangerous, and men often set up checkpoints there. (Credit: Marie Jo Sader/OLJ)

The Halba municipality seems like a haunted administration on this winter’s night. The phone inside the building keeps ringing. It is 11 p.m., and no one is there to answer the call.

“It’s always like this,” says Abdelkader, who is not the least bit annoyed by the phone that does not stop ringing.

Abdelkader, 28, is a municipal policeman. Every night, he joins some 20 other men at the entrance hall of the municipal building to sign the attendance sheet before leaving for patrol.

Divided into squads, they drive their patrols to different locations within Halba, where they keep a nightly vigil until 5 a.m.

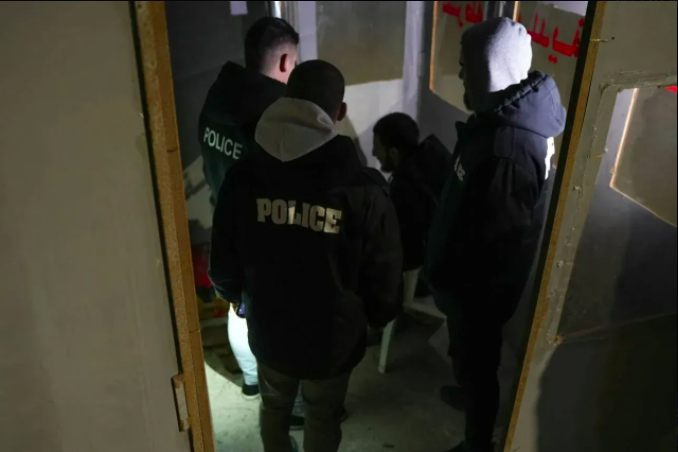

Although wearing a black jacket embroidered on the back with the word police, most of these men are not police officers, but rather civilians from the locality. They proclaimed themselves “night vigilantes” in Akkar, where thefts and smuggling rings have become rampant in this area near the Syrian border.

‘We do the police’s job’

Amid an unprecedented economic meltdown that has plunged three-quarters of Lebanon’s population into poverty (according to UN figures), there has been an increase in petty crimes in Akkar, similar to other parts of the country.

Ostensibly, security forces have been unable to end this phenomenon due to a glaring lack of means and manpower. The number of desertions in the police ranks has been on the rise since salaries deteriorated dramatically due to the dizzying devaluation of the national currency and ensuing rapid inflation.

“Automotive batteries, tires, scooters, electric cables … organized gangs are committing more and more thefts in the area, which raised serious complaints among the residents. Since security forces have become unresponsive and stopped patrolling, we have been forced to make up for this. We are doing what the police are supposed to do,” explains Abdelkader.

Halba night guards gathered in the entrance hall of the municipality building before their vigil, which will last until 5 a.m. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

Halba night guards gathered in the entrance hall of the municipality building before their vigil, which will last until 5 a.m. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

These Halbans, who are mostly under the age of 30 and all claim to be part of the October 2019 thawra movement, volunteered to protect their home from thieves.

With the consent of the municipality, which gave them four vehicles, they installed seven points of presence in the city, enabling them to keep an eye on all vehicles from the moment they enter to the time they leave Halba.

‘We are not armed’

The night mission begins for each of the squads. Abou Sami and two of his colleagues are stationed on the side of the road at the sensitive “Heker” point. It is impossible not to see them with the vehicle’s headlights turned on.

Abou Sami, 58, is the oldest in the squad. “This is the entrance to Halba, it is the most dangerous point. We used to have a barricade here, when there was more traffic,” he says with a hoarse voice and a Robin Hood hat on his head.

It was a quiet night and the faces of the rare cars’ drivers that passed were familiar to the security guards. “Not much happens most of the time, because everyone in Akkar is aware that we’re here now. They no longer dare to risk it.”

These activists claim to have already arrested several bandits from the surrounding localities, including Denbo, Hosnyeh or Birqayel. Although their mission involves some dangers, they did not receive any special training. It was the experience that forged them, they say. They faced life-threatening incidents, but were not subject to any armed assault.

“Yes, we could give a slap or blow when we arrest a thug,” Abou Sami says, “But we are not armed,” he adds.

‘The residents have never been so safe’

A few hundred meters further, Abdelkader and five of his fellows are positioned at the “Maleheh” point, where there is a small white cabin, with the inscription “Municipal Police.”

“Three of us stay inside the cabin in general, which includes a wood-burning stove to keep us warm, while the other two watch the vehicles on the roadway, and we take turns. We also conduct patrols near sensitive commercial establishments,” says Zyed, 26, with a strong Akkar accent.

Security guards monitor vehicles from their time of entry in Halba to until they leave. When in doubt, cars are stopped and searched. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

Security guards monitor vehicles from their time of entry in Halba to until they leave. When in doubt, cars are stopped and searched. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

“We trace every car that passes through Halba. If we don’t see it exiting the locality, we track it down to find out where it is parked. When we have doubts, we stop the car, open the trunk and ask questions. In case we find stolen items, we restore them [to their rightful owners],” Abdelkader further says.

A few days earlier, they got their hands on stolen scooters, which they handed over to their owner. The two men sniggered when they recalled that the official police force refused to handle the crooks.

“There are times when a thief needs to be handed to the police at night, but they refuse to receive us because they’re sleeping,” says Abdelkader.

According to them, it has been a while since Halbans have not felt that safe. “Something happens in Akkar every two minutes, but almost nothing has happened here since we have been there,” Abou Sami proudly says.

The only municipal policemen in this squad are Abdelkader, Zyed, Khaled, Assem and Mohammad, who earn a monthly salary of LL1.2 million (about $60 when calculating at a conversion rate LL20,000 to the US dollar). The others are volunteering their services. While a handful of the men have a job to go to during the day, most are unemployed.

However, the latter ended up receiving financial aid from several businesses and some major Halban families. These donations amount to LL18 million (nearly $900 at an exchange rate of LL20,000) that the nearly 20 volunteers divide among each other every month.

It is a nominal sum that barely enables them to pay for gas, cigarettes and coffee expenses when they are on shift, these young men say.

“I have a job and I make ends meet, but I am committed to protecting the village. This sum that we receive at the end of the month is the last thing I care about,” claims Ali, clearing any doubts about the watchmen’s motivation, at a time when Akkar, the poorest area in Lebanon, is struck by the crisis harder than any other part of the country.

However, many of the squad members bank on these donations and have no other source of income. “I used to be a concrete construction worker, along with my brothers, but we haven't had a job for four years, and all construction works were halted in the area since the thawra,” says Adel, whose two brothers and two cousins are also night watchmen.

Return to ‘amen zete’ (self-defense)?

As it sought to manage the traffic during the crises and subsequent [fuel] shortages in the summer, this group of young men became known to the locality’s inhabitants and earned their trust. “The people are glad to assist us. Their donations prove that they love and support us,” says Abdelkader.

Guards momentarily warm up around a stove in a cabin on the side of the road, while their comrades check vehicles. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

Guards momentarily warm up around a stove in a cabin on the side of the road, while their comrades check vehicles. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

However, their action is not met with overwhelming support at present. They are accused of thuggery by some. Others claim that they have firearms and behave like private militias. The case was even addressed in a meeting for the locality. These young men are blamed for proclaiming themselves as guardians of the city and making the rules without any supervision.

Halba’s municipal council has been in fact dissolved in 2018 due to internal political rivalries. Ever since, the municipality has been managed by Akkar’s governor, Imad Labaki, who ensures continued delivery of the most basic public services.

“Initially, the inhabitants gave them money to encourage them, but now, they are the ones who oblige the people to pay them on a monthly basis under the pretext that they guard their businesses,” says a resident who declined to be named.

According to Labaki, these claims are unfounded and driven by rivalries among families. “A single piece of evidence proving that these men are extorting money from the locals or blackmailing them would be enough for me to have them arrested. But no one provided any evidence or complained, why?”

In the city center, where exchange offices and shops for jewelry, electronics and clothes stand next to each other, a dozen interviewees among the locale’s merchants expressed satisfaction with the presence of these security watches. However, we did not encounter anyone who claimed to have offered the volunteer watchmen financial support.

It is not only in Halba that one is able to see residents gathered nightly to stand watch. The phenomenon extended to several villages in Akkar, including Jdide and Miniara. Yet, many have refused to compare the current situation to the dark memories of the Civil War during which militias ensured the protection of neighborhoods in the name of “amen zete” (self-defense).

In Miniara, which is less than 3 kilometers away from Halba, the volunteers said they are active in the community out of pure love for their village. “It’s just a way to protect our homes and property from thefts and the massive presence of Syrian refugees in the area. Our men, many of whom are retired soldiers, do not take a penny in return,” Tony Abboud, mayor of this locality with 12,000 inhabitants, proudly says.

Imad Labaki, the governor of Akkar, who supports the vigilantes. He administers the municipality of Halba, whose council was dissolved in 2018. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

Imad Labaki, the governor of Akkar, who supports the vigilantes. He administers the municipality of Halba, whose council was dissolved in 2018. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

A common characteristic of state collapse

“There is no doubt that it is neither good nor plainly legal. It is the security laissez-faire that led these young people to act as security watches. It's a jungle right now here and you can't just ban people, whose property could be stolen, from standing guard!” Labaki says.

Yet, he did not note with concern the fact that these young men are present in the streets without having the training nor equipment to secure a city, which has a population of 30,000 inhabitants and is subject to further security incidents.

The state is to be blamed for this longstanding neglect of Akkar, where all the characteristics of a poor and relatively isolated rural community, lacking real infrastructure and public services, are present.

“I’ve been seeking to meet with the interior minister for a while,” says Abboud. “We have no budget and if we ought to continue to protect Miniara, they must either grant us firearms permits for our security watches or increase the number of policemen,” says the locally elected mayor.

The Interior Ministry’s answers to questions from L’Orient-Le jour on the town protectors initiative were evasive. It said, “Security forces are carrying out their duties under the current circumstances, and stand in solidarity with the citizens.”

Tony Abboud, the mayor of Miniara, a village who has also set up a group of night vigilantes. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

Tony Abboud, the mayor of Miniara, a village who has also set up a group of night vigilantes. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin/OLJ)

“It is a general situation that not only applies to us here. The state does not even have the means to repair police cars and dozens of servicemen resign every day. What do you want MPs to do?” Hadi Hobeiche, who has been an MP for Akkar since 2005, says. For him, “The least someone can do is to protect his locality amid a crisis.”

“Villagers in Lebanon have always stood guard in times of insecurity. I do not see where the problem is. It is true that they can be exposed to direct fire, but who does not possess a firearm in Lebanon?” he asks.

The population blames Akkar’s MPs for their clientelist practices and their lack of interest in the region, which helped Akkar become a longstanding impoverished district at risk of chaos.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury