Despite wheat import subsidies, the price of bread in Lebanon has risen at the same rate as inflation. (Credit: Mohamed Azakir/Reuters)

BEIRUT – At the end of last week, with the lira rallying to just below LL24,000 to the dollar, the Economy Ministry announced a drop in the price of bread. Despite this small respite in the seemingly endless rise of prices across Lebanon, bread prices remain more than double what they were just six months ago.

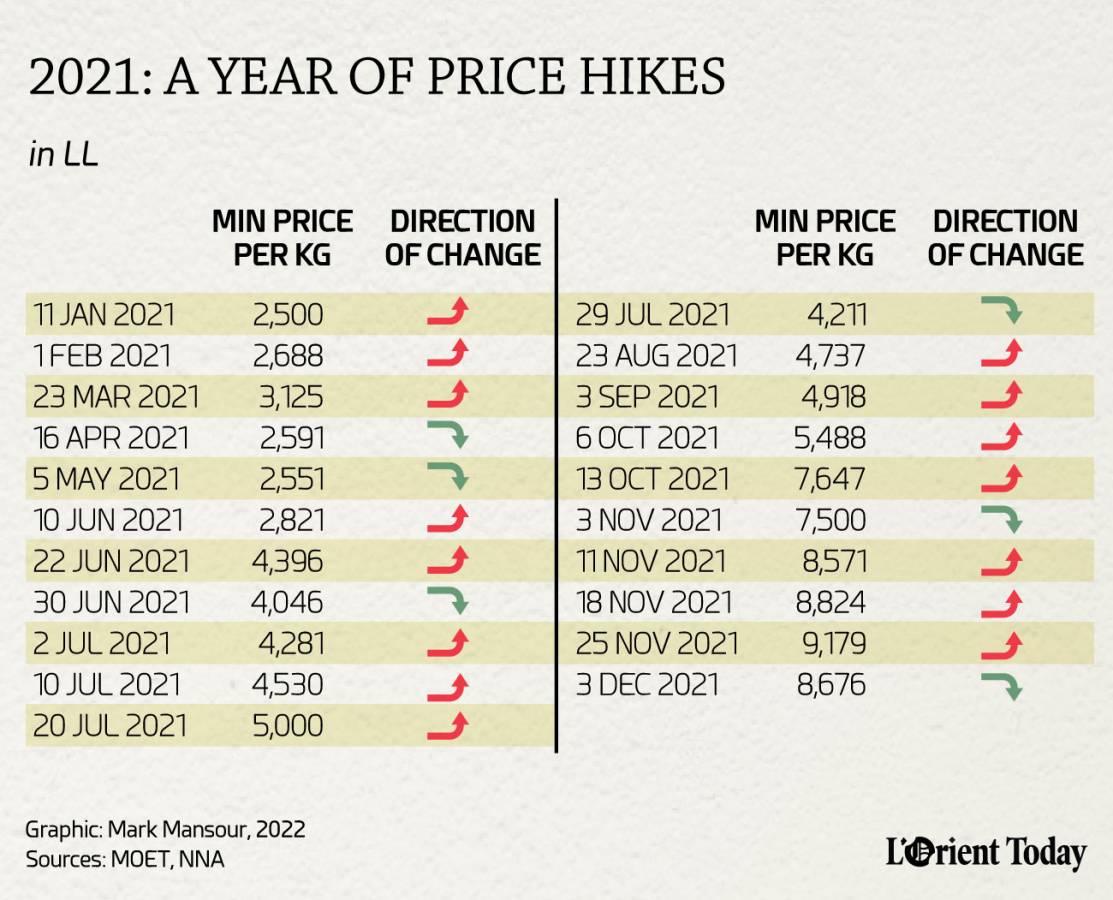

Bread is subject to price controls and subsidies — notably, on wheat — but its cost has still risen sharply over the past two years, with its price rising from LL1,500 for a 1 kilogram package at the beginning of the crisis to between LL10,233 and LL15,714 per kilogram now, depending on the size of the package. This is down from last week’s record high of LL11,429 to LL17,391 per kilogram.

Whereas prior to the crisis there was just one price, for a large bundle of bread that varied over the years in weight from 1 to 1.5 kilograms, prices are now set for three sizes, the exact weight of each being adjusted with each price change, but which roughly range from 0.35 to 1 kilogram. In the time of the crisis, the once-standard weight of around 1 kilogram has been christened the “family bundle.”

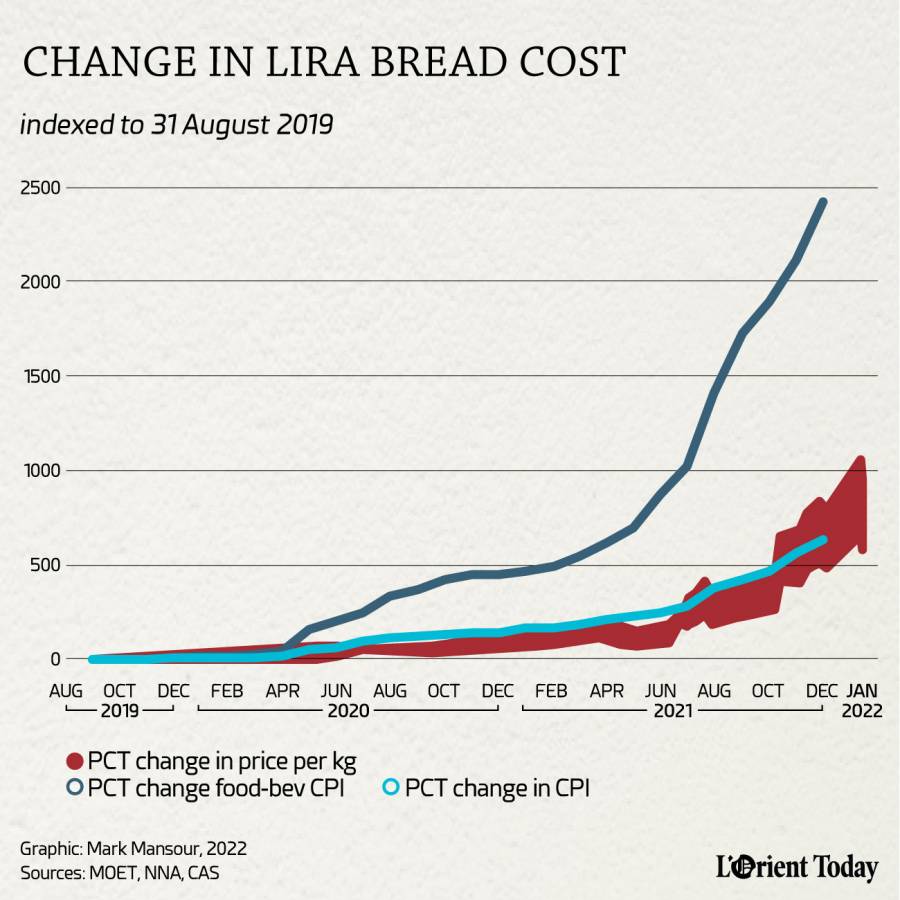

Taking into account the different packages on offer, the cost of bread per kilogram in lira has risen by 582–948 percent since August 2019, compared to a rise in the consumer price index of 629 percent as of the most recent data.

Prior to the Jan. 14 price drop, announced on the back of a rallying of the lira at the end of last week, the rate of inflation in bread prices stood even higher, at 662–1,059 percent, again compared to a consumer price index rise of 629 percent to date.

However, the increase in bread prices is significantly lower than that of food and non-alcoholic beverages as a category, which have increased by an astronomical 2,422 percent since the start of the crisis.

In other words, while subsidies and price controls have kept bread below the rate of inflation seen in food and non-alcoholic beverages in general, bread prices have kept pace with the general economy’s devastating inflation, raising questions as to whether subsidies and price controls have achieved their intended purpose.

Salem al-Habr, who owns a small bakery in Ain al-Rummaneh, said that as of today subsidized wheat makes up just 10 percent of his cost for producing Arabic bread, with non-subsidized inputs priced in dollars making up 90 percent of the cost.

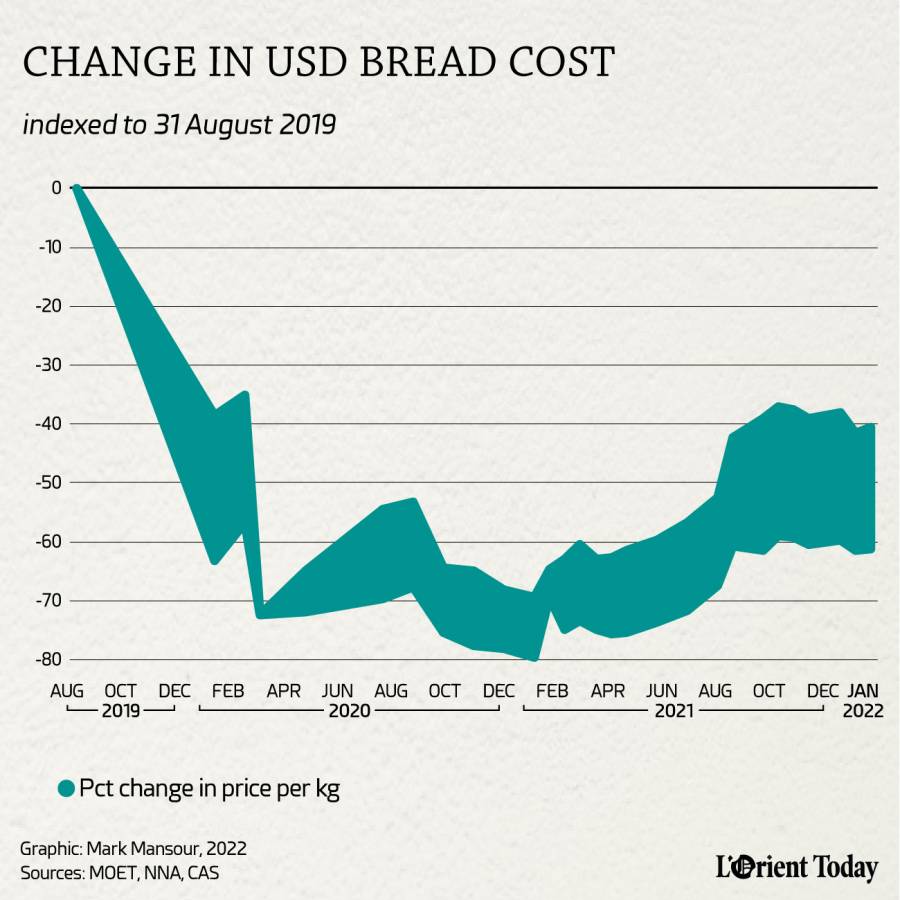

In dollar terms, revenue from the sale of a package of bread is markedly below pre-crisis levels, even while that bread becomes more and more unaffordable for millions in Lebanon.

“A bundle of bread used to cost LL1,500, and the dollar was LL1,500, so its price was a dollar,” said Habr. “Today a package of bread costs LL9,000 and, on the dollar, it’s 30 cents, more or less. And on top of that we buy everything in dollars. Oil we buy in dollars, diesel we buy in dollars, nylon is in dollars, yeast is in dollars, sugar is in dollars, salt is in dollars … There’s nothing except flour that’s in lira, and it’s obviously expensive.”

If a piece of machinery breaks, replacement parts will also be priced in dollars, and his generator bill for a small bakery with a single production line is LL50 million per month, Habr said.

For him, the high cost of bread in lira and the low revenue in dollars is a double bind.

“[The price] is not enough, but our hearts ache, honestly,” he said. “In this work, in this field, one keeps compassion for the people and feelings for the people.”

Bread industry

Bread is a basic foodstuff in Lebanon. The most recent survey of household expenditures, from 2012, found that the average household in Lebanon spent 14 percent of its food budget on bread and cereals. Put differently, just under 3 percent of what a typical household spent on all expenses, from rent to health insurance to car payments and clothes, was spent buying bread.

At a macro level, BLOM bank estimated that Lebanese households spent $23.5 million per month on bread in 2012, consuming roughly 785,000 packages per month.

After the lira began its crash in late 2019, Banque du Liban launched a subsidy scheme that allowed importers of certain products to exchange their lira for the dollars needed to pay foreign suppliers at rates far below those found in the open currency exchange market.

In 2020, the value of Banque du Liban’s wheat import subsidy was roughly $12 million per month, said Georges Berberi, director-general of the General Directorate of Cereals and Sugarbeets in the Ministry of Economy and Trade. In 2021, due largely to a rise in global wheat prices, the amount spent on the subsidy rose to some $20 million per month, with the amount of wheat imported remaining similar to 2020.

The central bank supplies wheat importers with dollars at the official rate of 1,507, but a BDL spokesman was unable to confirm whether the full amount is subsidized at that rate.

The vast majority of wheat used to make Arabic bread is imported, mostly from the Black Sea region, with domestic wheat production making up only a small portion of the total supply.

Imported and domestic wheat is milled into flour locally by Lebanon’s dozen mills. Just four mills produce 70 percent of the flour made in the country. Imported flour, on the other hand, most of which is milled in Turkey, makes up just 4 percent of the market.

The government has historically bought wheat from local farmers at above-market rates, in order to subsidize local agriculture, but this industry isn’t large enough to impact the price of bread. Amid the crisis, however, the program has effectively halted since 2019. The government has also, in the past, purchased wheat from overseas and resold it to local mills at a discount as a subsidy.

During the economic crisis and continuing into the present, BDL has been subsidizing wheat imports via a preferential exchange rate. In 2020, BDL subsidized 50,000 metric tons of wheat imports per month, Berberi said. This is enough to produce just under 40,000 tons of flour, of which the majority (27,000 tons) is for Arabic bread. In 2021, BDL approved imports of 630,000 tons, a 5 percent increase in tonnage, in light of the country’s crisis, Berberi said.

Prior to 2019, the mills, collectively via their union, set the price of flour for the bakeries without government intervention. Since 2019, however, the mills and the Economy Ministry have agreed to adopt a periodically updated price schedule.

According to a 2019 study conducted by British international development company Crown Agents, 258 bakeries bought the T85 type of flour, which is used to make Arabic bread, in 2018.

But the bakery market is also highly concentrated. Between 54 and 55 percent of the bread is produced by just five players, according to a 2017 study by BLOM Bank. Chamsine leads the market, producing over a fifth of Lebanon’s bread, followed by Wooden Bakery, Moulin D’Or, Al Sultan and Pain D’Or. Some 250 other bakeries, mostly small neighborhood businesses, share the other 45-46 percent of the market.

Price wars

Because of bread’s basic importance, its price has long been regulated. Laws setting bread prices can be found in the official gazette dating back at least to 1935, although they are likely older. The current pricing system dates back to 1959, with the creation of the GDCS, which makes recommendations on prices to the Economy Minister. From 2011 until 2019, the GDCS used a pricing model prepared by a consultant.

The DGCS requested assistance updating the bread pricing formula under the EU-funded Technical Assistance Facility, a program to upgrade the government’s capacities. Consultants from Crown Agents conducted their study, completed on Aug. 30, 2019, and devised a new pricing formula.

According to then-Economy Minister Mansour Bteish, the redacted portion of the study showed that bakeries earned a 10-12 percent profit margin on the sale of Arabic bread, to say nothing of the much higher profit margins achieved in the sale of specialty products that are not price-controlled, like baguettes, kaak, pain au lait, cakes, cookies and manakeesh. BLOM bank previously estimated that 50 percent of bakery revenues come from non-bread sales.

Even before the country’s economic crisis, the country’s large bakeries had been calling for an increase in bread prices. The August 2019 Crown Agents report noted that “small bakers,” on the other hand, were satisfied with the prevailing prices. Crown Agents advised the ministry that “notwithstanding pressure from the industry there is no immediate need for [prices] to be revised.”

By October 2019, industry pressure on the Economy Ministry to increase bread prices was rising, but the ministry refused to increase prices, accusing the bakeries of attempting to “exploit the circumstances to achieve additional profits at the expense of a morsel of the poor.”

In December 2019, the bakeries struck out on their own, collectively acting to reduce the bread bundle from 1 kilogram to 900 grams, functionally raising the price per kilogram to LL1,666.

The Economy Ministry refused to budge, claiming that a special “work team” had conducted an up-to-date field study establishing that the then-current cost to produce 1 kilogram of bread was LL1,000, leaving bakeries with a 33 percent profit margin on the sale of bread at the official price.

By February 2020 the price wars had intensified, with bakeries threatening a strike in response to attempts by the new economy minister Raoul Nehme to control pricing. Nehme proposed a committee to study the cost of producing bread and, by extension, its price for consumers. The committee was composed of representatives of stakeholders including government, bakeries and labor.

According to the bakery workers’ union leader, Shehadeh al-Masry, in March 2020 the ministry told him the committee’s work was indefinitely postponed due to the country’s coronavirus lockdown, he said. But then in May it issued new prices indicating to him that the committee had met without him.

He charged that the bakeries were playing tricks, like using subsidized flour in the manufacture of non-price-controlled products with high margins like cakes and manakeesh, and that they were underestimating the bread yielded by each bag of flour received, in order to hide their true profits.

A representative for the Federation of Bakeries Syndicates did not respond to requests for comment.

Then, in 2021, the bottom really dropped out. The per kilogram price of bread was increased 15 separate times that year, compared to just eight times from 1991 to 2020.

Masry said he tried to get access to the formula being used to set prices, with an eye towards challenging the bakery owners and the ministry, but the ministry refused to share the formula, saying it contained trade secrets. Masry and the civil society NGO Legal Agenda brought a case before the state Shura Council, which, in July of last year, ruled that the ministry had to release the formula, according to Legal Agenda.

Masry confirmed he has not yet received the formula. An Economy Ministry spokesperson did not respond to questions about the matter other than to say “the formula is not public.” Berberi said he will not give Legal Agenda the study and questioned their motives for wanting it.

In 2021, BDL had increased its expenditures on the wheat subsidy from roughly $12 million per month to $20 million per month, and increased the volume of wheat imported by 5 percent, but hours of state electricity provision dropped throughout the year and, in August, fuel subsidies started being slashed, driving the cost of doing business in Lebanon sharply higher.

In June 2021, BDL’s nonpayment of sugar subsidies was blamed for a 16–21 percent increase in the price of bread bundles. Making Arabic bread generally requires about 35 kilogram of sugar for each ton of flour, Antoine Seif, CEO of Moulin D’Or bakery, previously told L’Orient Today.

Many progressives inside Lebanon have called for the subsidy regime, which has largely been phased out with the exception of wheat imports, to be replaced with a targeted social safety net, but over two years into the crisis, the deadlocked political class has yet to be able to implement any such program.