Very little light reaches street level in the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

BEIRUT — Squeezed between the tightly packed buildings of the Mar Elias Palestinian refugee camp on May 20, dozens of people draped in their nation’s flag and traditional black-and-white kuffiyeh scarves prepare to march.

As they emerge from the narrow, brightly painted walkways of Lebanon’s smallest official camp and set off across Beirut, they chant messages of solidarity with Palestinians in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood and Gaza facing Israeli aggression.

“The struggle of Palestinians in Palestine is also our struggle,” Rasha, a 23-year-old Palestinian refugee from Syria and resident of the camp, who asked for her name to be changed, told L’Orient Today. “We are all united, we have one identity.”

Once the march is over, many will return to their homes in the 200-meter-square concrete maze that is the Mar Elias camp. Buildings are wedged in beside each other, with multiple stories and precarious staircases letting little light down onto the pathways that in many places are barely wide enough for a motorbike to squeeze through.

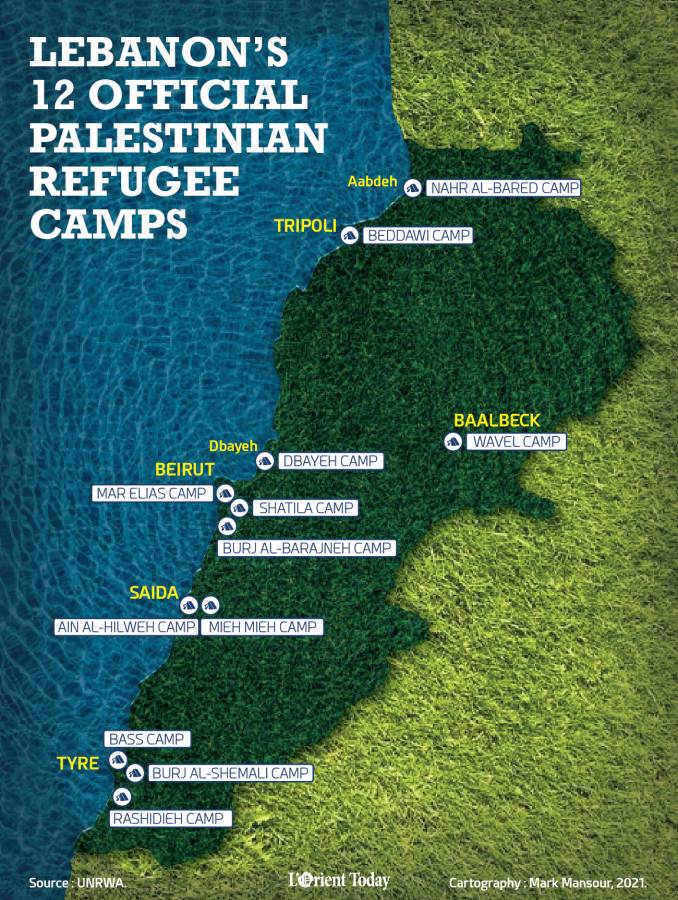

Just under half of Lebanon’s estimated 207,000 refugees (including 27,700 displaced from Syria since 2011 due to the conflict there) live in one of 12 official camps served by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine (UNRWA).

These 12 are what remains of at least 15 refugee camps originally set up between 1948 and 1955, the perimeters and locations of which were proscribed by the Lebanese state.

Israeli aerial bombardment destroyed the Nabatieh camp in 1974, and in 1976 Christian militias besieged the Tel al-Zaatar and Jisr al-Basha camps in northeast Beirut, as well as the Dbayeh camp, killing between 1,500 and 3,000 Palestinians and all but destroying the camps. Of these, only the Dbayeh camp still stands today.

Living conditions are poor, due to overcrowding, poor infrastructure and decades of neglect and discrimination as shelters originally meant to be temporary remain in place, seven decades later.

Where did Palestinians in Lebanon arrive from?

Around 100,000 people fled from Palestine to Lebanon between 1947 and 1949, fleeing “either direct expulsions and aggressions or leaving out of fear,” explained Anne Irfan, a lecturer at Oxford University’s Refugee Studies Center who has specialized in UNRWA and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

They were among the more than 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled from their homes as part of the 1948 Nakba, or catastrophe, following the declaration of the state of Israel and the ensuing Arab–Israeli war.

The majority of those who came to Lebanon hailed from areas of northern Palestine, such as around the Sea of Galilee, Haifa, Safad and Acre (Akka).

Further waves of Palestinian refugees arrived following the 1967 Arab–Israeli war, which saw Israeli forces capture the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Gaza strip and the Sinai peninsula, and the 2011 war in Syria.

“The relationship between Lebanese and Palestinian societies has always been historical with close ties between them,” said Anis Mohsen, a Palestinian writer and researcher at the Institute for Palestine Studies, explaining that before the Nakba, it was common for Palestinian and Lebanese traders to move across the border for work.

Those who arrived following the Nakba can mainly be divided into two categories, Mohsen added — the wealthier, urban class who moved to Lebanon’s coastal cities, and the rural population, many of whom ended up in what developed into refugee camps.

Early camps

In the late 1940s, most of the rural population who arrived in Lebanon lived in tented settlements, while receiving support from local and international charitable organizations such as the Red Cross.

“It was overwhelmingly tented settlements in the early period, and over the years they came to resemble the semi-permanent structures we see now,” Irfan said. While most refugees initially found shelter in southern Lebanon, the Lebanese government made concerted efforts to disperse them to camps across the country, she added.

In 1949, the United Nations created UNRWA to provide emergency relief to displaced Palestinians and it began operation in Lebanon in May 1950, offering food, clothing and soap rations. Only later would the agency start supporting the development of the camps themselves.

“The camps were mostly just tents to shelter refugees from the heat of the summer and the cold of winter,” said Hasan Mneimneh, the head of the Lebanese-Palestinian Dialogue Committee.

Some camps already existed. The El Buss camp, for example, located near the roman ruins in Sur, was originally designated by the French mandate in 1937 as a camp for Armenian refugees. Many of the camp’s original Armenian residents moved to the town of Anjar in the 1950s to make way for Palestinians fleeing their homes in northern Palestine.

Other Palestinian refugees were sheltered in existing structures. The Wavel camp in Baalbek was originally a barracks for the French mandate’s military, and its 12 buildings provided shelter for Palestinians fleeing in 1948.

Canvas to concrete

However, as it became clear that Palestinian refugees would not be able to return to their homes in occupied Palestine any time soon, they began to construct more permanent structures for themselves and their families.

“After the tents, refugees began using whatever they found — thick cartons, mud bricks for example — and then with time they began building solid walls,” said Daoud Korman, the head of the camp improvement and infrastructure program at UNRWA Lebanon.

While it was refugees themselves who built the shelters, UNRWA initially provided roofing materials.

UNRWA was initially only given a three-year mandate; this has been repeatedly renewed over the years. For Hoda Samra, UNRWA’s senior media and communication advisor, this is an indication of the idea that the Palestinians’ displacement in Lebanon would be short-term.

“Everyone thought it would come to an end — no one expected they’d be accommodated in these camps for over 70s years,” she said.

Manal Kortam is a Palestinian-Lebanese activist, whose family hailed from a village near the city of Haifa and later moved to the Beddawi camp. “My family and the other Palestinians did not imagine they would stay in Lebanon — the temporary has become permanent,” she said.

Because year after year the camps continued to be perceived as a temporary housing solution, construction continued apace without any strong consideration of longevity. The result: overcrowding, poor infrastructure and unreliable water, sewage and electricity.

“There would never have been an organized plan because no one could have known what was going to happen,” Korman said. “Everyone thought it was temporary.”

Many of the camps suffered severe damage during the 15-year Lebanese Civil War and Israeli invasion in 1982, which destroyed hundreds of homes and vital infrastructure.

Building restrictions

The development of the camps into the cramped and often unsafe condition they are in today is also a result of Lebanese policy. The land allocated to refugee camps by the Lebanese state has barely changed since 1948, despite there being fewer camps to accommodate a Palestinian refugee population that has more than doubled, Palestinians are also prohibited from owning land and real estate.

“There is so much denial of Palestinians’ civil rights,” Irfan said, “and this expands to the fact that organic expansion and population growth is disallowed by Lebanese policy.”

With camps restricted to the original plots of land set out by the Lebanese government 70 years ago,Palestinians are forbidden from building outwards. They are left with only one choice — to build upwards.

A street vendor waits for customers in an alley of the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

A street vendor waits for customers in an alley of the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

The camps are extremely densely populated, with buildings constructed haphazardly, close together and with stories piled on top of each other and rooms added on when necessary.

“They built blocks on top of blocks on top of blocks with no foundations,” Moshen said. “It is not safe to live in such houses.”

UNRWA estimates that there are around 6,500 shelters across the country that are in need of rehabilitation, Korman said, but the agency has not been able to secure funding to conduct the repairs.

Abu Ali is a 55-year-old Palestinian resident of the Mar Elias refugee camp. Born and raised in the Tel al-Zaatar camp, he moved to Mar Elias following its destruction, and says the situation there has deteriorated over the decades.

“There is no engineering,” Abu Ali said. “At any moment it could all fall down,” he continued, pointing to a four-story building at the end of the narrow street.

Just around the corner, an even taller, white painted tower of seven stories looms overhead, blocking out the sunlight and leaving the streets below gloomy.

“People just build randomly with no care for the health of others,” Abu Ali said.

High rates of chronic diseases, such as heart problems, pulmonary conditions and diabetes, among Palestinian refugees are likely linked to poor living conditions in the camps, Samra previously told L’Orient Today. The infrastructure itself also poses a risk — dozens of people have died after being electrocuted in camp alleyways due to the lethal combination of water and poorly managed power cables.

Manal Makkieh, a Palestinian activist in her early twenties who runs a group to support women in the Mar Elias camp, said that while technically it is illegal to build upwards, people get around the rules by using wasta, connections, or paying bribes.

“Things have changed over the years, but not for the better, for the worse,” said Makkieh, who grew up in the camp. “There are major problems with sanitation and electricity.”

“Before, I remember we had wide streets and you could see the sky, the sunset and even the beach … even in our lifetime the buildings are going higher and higher.”

Another consequence of the government’s ban on horizontal expansion is the creation of informal “gatherings” — collections of shelters usually built around the outskirts of camps. There are more than 150 of these settlements across the country. As UNRWA’s mandate is limited to the refugee camps themselves, residents in the settlements rely on other UN agencies and NGOs for assistance, Samra explained.

As Leila Khalili puts it in her 2007 book Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine, “the transience of life in the camps was partially reinforced by the Lebanese state’s refusal to allow any construction which could indicate permanent settlement.”

Lebanese politicians have long argued that giving Palestinians their full civil rights would undermine their right to return to their homes in Palestine, which is enshrined by the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194.

Initially, some Palestinian refugees rejected the establishment of more permanent structures and attempts by UNRWA to “beautify” camps, Ifran said, as it would undermine their right to return.

However, “the discourse of many Palestinians has changed over time,” Kortam said. “Previously, many believed that if we had rights, we would not return to our homeland …. But over time, they came to realize, through their dire living conditions, that getting their rights does not mean we won’t return.”

Meanwhile, Mneimneh said, “There is a common illusion that improving the conditions of the camps would lead to [Palestinians'] permanent resettlement in Lebanon ... Lebanese officials have a prepared excuse for abandoning refugee affairs.”

The result, he added, “is the continuous deterioration in the camps,” which is “dangerous for all who live there.”