Health care workers stand in line to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. (Credit: Mohamed Azakir/Reuters)

BEIRUT — A year on from the first recorded cases of COVID-19 in Lebanon, the launch of the vaccination campaign on Feb. 14 was celebrated as the first step on the road out of the pandemic.

But less than two weeks in, it has already been embroiled in scandal, disrupted by technical faults and criticized for its slow pace and lack of transparency.

In the first report by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the body tasked with monitoring the rollout, violations of the inoculation plan were recorded at 40 percent of vaccination sites.

Slow rollout, long wait for appointments

Over the last two weeks, dozens of people have taken to social media to question the pace of the vaccine rollout, complaining that their elderly relatives have been waiting weeks to get the notification that they can book an appointment, having registered on the Central Inspection Bureau’s Impact platform.

“The main problem is that the pace of appointments being given is slow,” Oussaima El Dbouni, an infectious disease specialist and the director of the vaccination center at Rafik Hariri University Hospital, told L’Orient Today.

“We have lots of patients coming and saying they have waited for two weeks after registration with no news from the Health Ministry.”

While appointments are delivered and booked via the Impact platform, it is the Health Ministry that controls how many appointments are offered and at which hospitals, according to a plan of the vaccination workflow seen by L’Orient Today.

Many hospitals are operating far below their maximum capacity for administering vaccines. At Rafik Hariri University Hospital, which has the capacity to administer 500 doses per day, the average daily number of doses given so far is 244.

The picture is similar at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, according to Umayya Musharrafieh, a family physician who is leading the vaccination campaign. It has the capacity to vaccinate more than 1,200 people per day, but so far the average is 544. At the Lebanese American University Medical Center-Rizk Hospital, only around 120 doses are given each day, while capacity is 600.

“It’s a waste of time and resources,” said Georges Ghanem, LAUMC-RH’s medical director.

Abdul Rahman Bizri, the head of the national committee on COVID-19 vaccines, said that the main factor in the slow rollout and lack of appointments is that there simply aren’t enough vaccines to go around.

“For the first few weeks, we are getting relatively limited numbers of doses,” Bizri said.

So far, just under 60,000 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine have been delivered to Lebanon, out of a total of 2.1 million set to arrive by the end of 2021. These doses are meant to go first and foremost to front-line health care workers and people over the age of 75. Some 87,000 of the latter group have thus far registered to receive the vaccine.

Bizri added that around 15 percent of the doses delivered so far are being held back so they can be administered as a second dose — required after 21 days to be most effective.

“At the moment, people just have to be patient,” said Mohammad Haidar, a medical advisor to the caretaker Health Minister Hamad Hassan, adding that by mid-March, around 500,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine are set to arrive in Lebanon. “This can really change the situation.”

Missing data

In theory, all data on the vaccination campaign should be logged on the Impact platform to allow health authorities and the general public to monitor progress.

However, a lot of that data is missing and thousands of vaccinations are going unrecorded.

At the end of the first week of the campaign, only around 50 percent of doses had been administered through the platform. In a leaked document from the Central Inspection Bureau, some hospitals were found to have administered up to 92 percent of their allotted doses outside the platform.

“When the campaign started, the Impact platform did not connect well with IT systems in many vaccination centers, so many started giving to over-75s without an official appointment,” Bizri said.

Several hospitals tried to boost vaccination numbers and ensure that doses did not go to waste by inviting those over 75 who had registered on the platform but not yet received an invitation for an appointment to call directly and book a slot. Others used their own internal systems to identify people from the first priority group for vaccines.

In an effort to curb such action, the Health Ministry issued a statement on Feb. 18 saying that only appointments booked via the Impact platform were permitted.

Their own statement was contradicted, however, when it emerged that MPs and Parliament staff, some of whom are under 75, had received the vaccine. The outgoing health minister said he had sent the ministry’s mobile clinic to Parliament to vaccinate MPs as a “token of appreciation for their efforts” in passing the law that allowed the emergency use of COVID-19 vaccines.

The vaccinations given to MPs, Parliament staff, President Michel Aoun, his entourage and the first lady via the Health Ministry’s mobile clinic have not been logged on the official vaccination platform. In fact, the mobile clinic no longer appears as a vaccination site on the platform.

Haidar said data from the mobile clinic will be entered into the platform in the coming days, alongside all other data on vaccinations that took place outside the platform over the last two weeks.

MP Fadi Alame (Amal/Baabda), a member of the parliamentary health committee, told L’Orient Today that he has sent a letter to the Health Ministry requesting increased transparency on the vaccination rollout.

“What I am trying to push for is a daily report, like we get for COVID-19 numbers, that shows everything from appointments booked, current vaccine stock and the vaccines given at each center each day,” he said.

Georges Attieh, the head of the Central Inspection Bureau, said he has also called on the ministry to be more transparent and share the data it has collected from vaccination centers “as its minimum” obligation.

“This is all we ask so that we can do our job and do oversight,” he said. “We are the audit department of the state.”

According to Bizri, the vaccine committee is working to tighten surveillance of vaccine centers and address issues ahead of the arrival of more doses.

“We are now gathering all the data from centers to look critically at the campaign so far,” he said. “Centers not complying will be dealt with harshly.”

The Health Ministry has already suspended the accreditation of three hospitals as vaccination centers for violating terms of the vaccination plan.

Hospital discrepancies

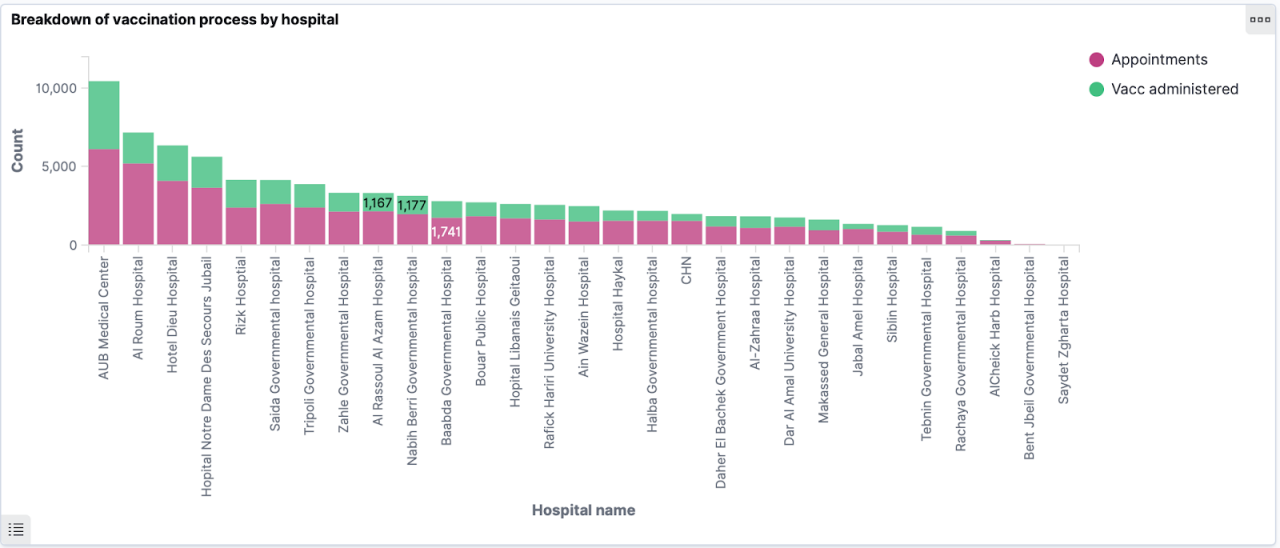

When looking at the Impact platform data, there are wide discrepancies between the number of doses being given at each hospital, with private hospitals in the capital leaps ahead of governmental hospitals.

“There are huge discrepancies in dispensing and distribution of vaccines and appointments,” Ghanem said. “The vaccination campaign started with a lack of transparency from day one.”

A screenshot of vaccination and appointment data, broken down by inoculation center, from the Impact platform.

A screenshot of vaccination and appointment data, broken down by inoculation center, from the Impact platform.

Bizri explained that the main factor in the differences between hospitals is capacity, as doses and appointments are distributed according to capacity.

However, Dbouni suggested that the environs of each hospital and the community each serves may also play a role in the number of appointments being booked.

“In the area around RHUH and the community, you should consider that a lot of people might not have a cell phone or are not familiar with the application” used to register for the vaccine, she said, adding that those with high disposable incomes might be more likely to visit private hospitals, as they are given the option to choose.

Haidar agreed. “In Lebanon we have a highly privatized health care system and people don’t believe in the public sector — this is the reality.”

“If someone in Beirut is given the choice between AUBMC or RHUH, they will choose AUBMC,” he said.

Nevertheless, the discrepancies aren’t as dramatic as they first appear — the missing data from vaccinations administered outside the platform can also skew the numbers.

For example, according to the platform, by Thursday AUBMC had vaccinated 3,989 people, while RHUH had vaccinated 836. However, according to figures provided by Musharrafieh and Dbouni, AUBMC had by Thursday vaccinated some 5,440 people, while RHUH had vaccinated 2,442.

Nevertheless, Bizri admitted that more work needs to be done to improve distribution of doses and the allocation of appointments.

“We are working to solidify the systems, so that we can better understand each hospital’s actual capacity,” he said. “We have to be prepared for the arrival of more doses.”

The next batch of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, comprising 41,120 doses, should arrive by the end of the week, according to the national vaccine plan.

That the vaccination campaign relies almost completely on digital systems also meant that errors in the initial rollout were almost inevitable, Haidar said.

“This is the first time in Lebanon that we are doing something completely digitally — it’s going to take some time.”