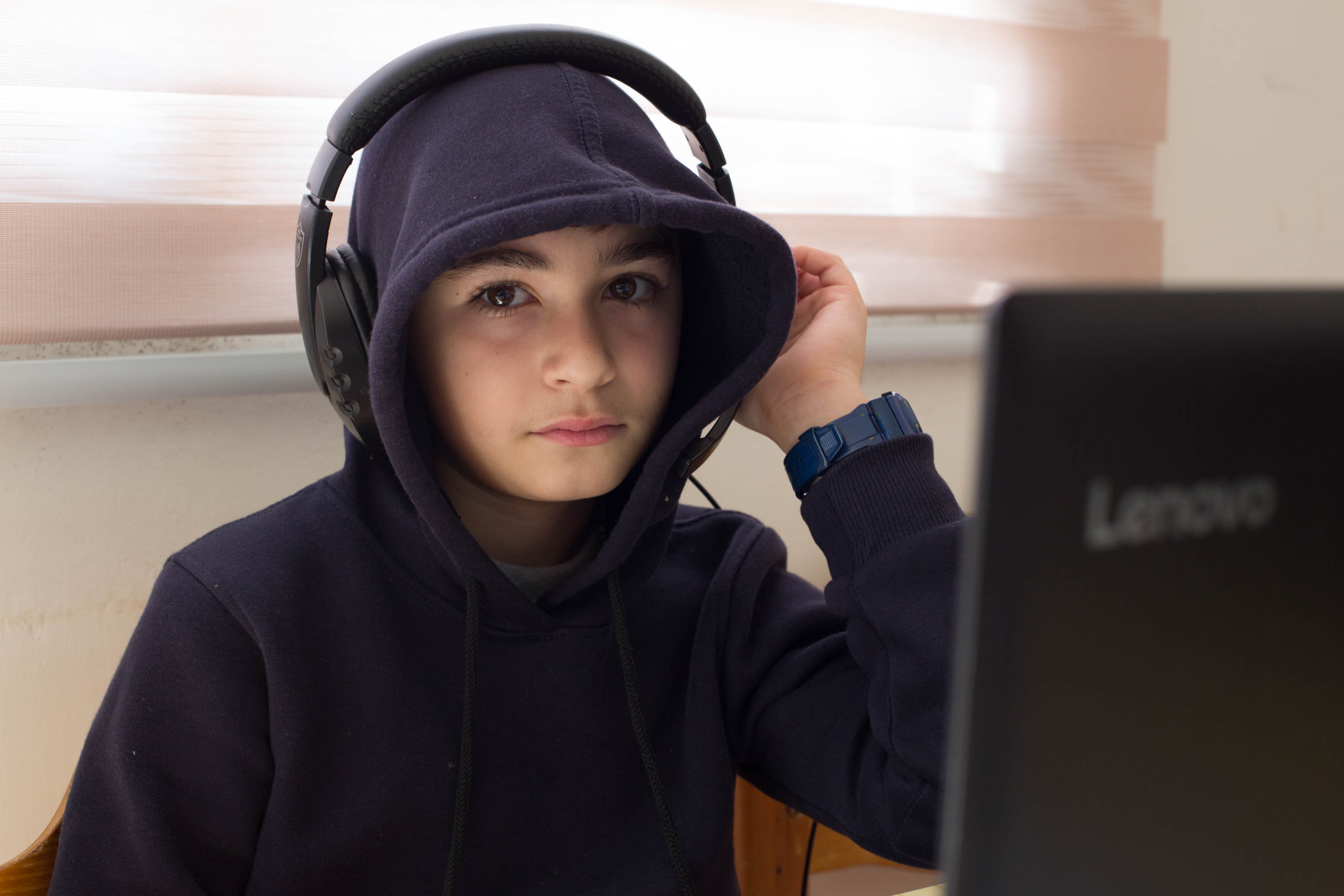

Ten-year-old Georges Mouawad, who fled southern Lebanon with his family and is now studying online. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

MOUNT LEBANON — “I prefer to go to an actual school, where I can play with my friends and understand the lessons better,” says 10-year-old Georges Mouawad. On Oct. 9, he fled Rmeich, a town on Lebanon’s southern border, with his mother, siblings and some extended family, as Israeli bombs began landing dangerously close to their home.

A student of Rmeich’s private school Notre-Dame du Liban, he now spends his free time between online classes playing with his brother and cousin in front of their summer house in Mount Lebanon’s Tourzaiya.

One morning in February, he had a session of Arabic, followed by sports and arts. “Our lessons often get interrupted, our teachers are disconnected,” he says.

“The subject I understand better is mathematics because our teacher is in Beirut and has a good internet connection.” Other teachers, just like their students, are either still in the south or have fled to elsewhere in Lebanon. Among the more than 90,000 people displaced due to the border clashes between Hezbollah and Israel, 37 percent are children.

Continuing to provide education remains a challenge for schools located in the South. Maha Farah, a French teacher, faces this challenge every day.

“Can you open your cameras? No? Are you all still in your pajamas?” She laughs in front of her laptop; her screen has become her classroom. She teaches grammar to 30 11-year-old EB6 students in their last year of primary school at the Collège Saint-Joseph Soeurs des Saints-Coeurs. The school, located in Ain Ebel, closed its doors on Oct. 9, just hours before bombs began to target the area.

Maha Farah, a French teacher at a school in south Lebanon, is now teaching online due to Israeli bombing in the area. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

Maha Farah, a French teacher at a school in south Lebanon, is now teaching online due to Israeli bombing in the area. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

On the following day, 55-year-old Farah packed some essentials and fled to a flat she owns in Mount Lebanon’s Ain Saade, her place of refuge during the 2006 war.

The Collège Saint-Joseph des Saints-Coeurs, which educated 1,000 students and employs 70 teachers, quickly moved its classes online — a necessity, as some of the students and teachers are being displaced, while others who remain in the neighboring villages would risk their lives to get to school.

This community has nonetheless paid a heavy price for the border clashes: an Israeli airstrike killed three of their students in early November and the Collège’s windows were shattered in another strike.

As of Feb. 16, UNICEF counted 44 closed public schools in southern Lebanon, affecting the education of 10,000 students. Among them, “approximately 5,000 children are engaged in remote learning through their original schools and around 1,700 children have been integrated into other nearby public schools, this number is expected to reach 3,200 children in the coming weeks,” the agency said.

Among those impacted are 500 teachers from Catholic schools in the South who have been teaching online, “and we estimate that 30 percent of them have left their villages,” according to Father Youssef Nasr, General Secretary of Catholic schools in Lebanon.

Ten catholic schools across the South have shut their doors, affecting 3,000 students, he adds.

Online and displaced by bombs

Farah experiences firsthand the shortcomings of online education. She is often interrupted in class by students' poor internet connectivity or outages.

“That’s okay, our lesson is being recorded, you can listen to it again on the platform,” she says, comforting her 11-year-old students. Behind her are two suitcases as well as an array of beauty products, three handbags and a pile of covers on a bed. Farah shares her flat with her husband, four nephews and nieces, her sister and brother-in-law. The kitchen and the living room are being turned into offices when necessary, while every sofa is used as a bed.

Maha Farah, a French teacher at a school in south Lebanon, is now teaching online due to Israeli bombing in the area. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

Maha Farah, a French teacher at a school in south Lebanon, is now teaching online due to Israeli bombing in the area. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

“There are ups and downs,” the energetic French teacher acknowledges. On the good days, she says that by becoming used to the situation, she “could carry on like this until the end of the school year.” Though the remote classes meant she could visit her children in France for two months, she is “not in high spirits.”

Still, Farah says she is “committed to [her] students.” She worries that the biggest disadvantage for her pupils is “the lack of human contact. They understand the lessons through my videos, but they are children, they need me.”

Farah is also anxious about the living conditions of her students: “Sometimes when I ask one of them to open his microphone, there is a lot of background noise; I don’t know if they have enough personal space.” She “dread[s] to ask them where they are, as some of them live in very exposed villages such as Houla.”

She laments the consequences of online schooling on her students’ learning process: while in the classroom she can instantly adapt her teaching to the difficulties of her students, it is an impossible task online.

Farah faced all these shortcomings already during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a vast majority of teachers in Lebanon had to teach online for many months. “But this time, it is different, it is only us: the teachers and students in the south,” she says. “Why the south is not considered part of Lebanon?”

“This war poses a threat to the education of our students,” Sister Hyam Habib, head of the private Collège des Soeurs des Saints-Coeurs in Marjayoun, says. “They suffer from the limited electricity supply, even though we adapt our online classes to the electricity schedule.” The internet connection has also deteriorated due to Israeli strikes on infrastructure. “Besides, some of our students are in modest families, and siblings have to share one device to attend,” Sister Habib says.

Ten-year-old Georges Mouawad, who fled southern Lebanon with his family and is now studying online. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

Ten-year-old Georges Mouawad, who fled southern Lebanon with his family and is now studying online. (Credit: Laure Delacloche/L'Orient Today)

The nun also stresses the psychological toll of the situation: “Our pupils are exposed to mourning situations, violence, trauma. Our children learn in front of their screens while hearing the bombing!” She lives on the school grounds, and has to run often to the shelter located in the school.

“These last two hours, out of 15 students, only five showed up on our online platform,” according to one teacher, speaking on condition of anonymity as the Education Ministry does not permit public school teachers to speak with the media.

Seventeen-year-old Razanne El Hajj, who before Oct. 7 attended a public school in Rmeich, is lucky to still be taking online classes. This year is important to her, as she has to take her baccalaureate exams at the end of the school year. She hopes to study at university and become a dentist.

She came back from her prolonged summer break on Oct. 9, only to remain at home in Rmeich afterward as the war began. Online education resumed in November, after a few weeks with no classes.

While Hajj says she’s confident about passing her exams, she finds her situation “unfair.”

“Until now, we have only covered a fourth of the curriculum because of the war, while the other schools across Lebanon have covered half of it, if not more.”

“I hope to return to actual school soon, and that the war will come to an end.”