Alfred Sursock Cochrane at his Georgian home in Bray, Ireland. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L'Orient Today)

This article is part two of a two-part series on architectural heritage between Ireland and Lebanon. Click here to read part one.

DUBLIN — Last month L’Orient Today reported on a team of Lebanese investors who were acquiring heritage homes in Dublin dating from the Georgian period in the 18th and 19th centuries. These Irish Georgian houses first captured the attention of the Lebanese community decades before the Hariri-linked investment fund Valpre Capital began its recent spending spree.

In the 1950s, Irish-Lebanese architect Alfred Sursock Cochrane’s mother, Lady Yvonne Sursock, and father, Sir Demond Cochrane, inherited and renovated the 19th-century Woodbrook Estate. An Anglo-Irish baron, Sir Desmond Cochrane also served as the first Irish ambassador to Lebanon and Syria while living at his wife’s Beirut residence, the Sursock Palace.

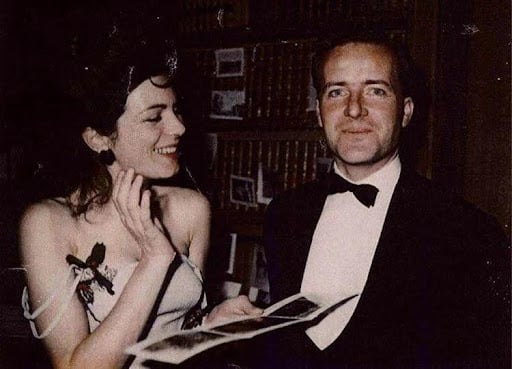

Desmond and Mariga Guinness. (Courtesy of: The Irish Georgian Society)

Desmond and Mariga Guinness. (Courtesy of: The Irish Georgian Society)

In 1958, the couple’s friends in Ireland, Desmond and Mariga Guinness, established the Irish Georgian Society to protect and conserve classical homes from demolition. Like buildings constructed in Beirut during the Ottoman era and under the French mandate, Ireland’s Georgian homes were at risk from zealous developers eager to bulldoze and knock down the structure and replace them with apartments and offices.

"When things started getting rather nice in Beirut in the late ’60s, my mother realized that wonderful whole streets were being pulled down," says Sursock Cochrane. "She felt she had to do something, having been inspired by Desmond and Mariga."

Alfred Sursock Cochrane is an architect who renovated his own Georgian home in Ireland, as well as several houses in Beirut’s Achrafieh and Gemmayzeh neighborhoods. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L'Orient Today)

Alfred Sursock Cochrane is an architect who renovated his own Georgian home in Ireland, as well as several houses in Beirut’s Achrafieh and Gemmayzeh neighborhoods. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L'Orient Today)

Workers from Maison Tazari re-installing the front door of the Sursock Palace after it was badly damaged in the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion. (Courtesy of: Maison Tarazi)

Workers from Maison Tazari re-installing the front door of the Sursock Palace after it was badly damaged in the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion. (Courtesy of: Maison Tarazi)

In 1960, Lady Sursock established in Lebanon an association known as Association pour la Protection des Sites et Anciennes Demeures au Liban (APSAD) to conserve Lebanese architecture and heritage structures. “The history of Beirut was being demolished and my mother saw that,” says Sursock Cochrane. “Nobody could understand what she was doing because all the people who owned an old house wanted to demolish their house and build an apartment block and be comfortable.”

Lady Sursock secured the support of Emir Maurice Chehab, a well-known archaeologist and head of Lebanon’s Directorate General of Antiquities at the time. “He was a civil servant with a certain amount of power and he could use some of his power to list buildings in Lebanon that needed preservation,” says Sursock Cochrane.

After training as an architect in Rome, Sursock Cochrane himself renovated several heritage homes in Achrafieh and Gemmayzeh in the 1960s and then later in the 2000s. “I worked with a team of incredible craftsmen,” he says. “Some are really artists for the quality of the tiling and woodwork they did.”

A damaged building in Mar Mikhael after the port explosion. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

A damaged building in Mar Mikhael after the port explosion. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

But victories for Lady Sursock and her campaign to preserve Beirut’s history were hard to come by. “How could my mother fight laws which guarantee somebody the total use of their property to do anything they want?” questions Sursock Cochrane. “It was a constitutional law. Like owning guns in America, owning property in Lebanon was sacrosanct — you couldn’t touch it.”

“It is unbelievable how dedicated she was to saving Lebanon’s heritage,” says Nabil Saidi, a Lebanese friend of Lady Sursock. “Whenever I saw her, she was always campaigning and talking about homes to be saved.”

After acquiring a Georgian home in Dublin himself, Saidi became a member of the Irish Georgian Society and organized a trip to Lebanon and Syria for the society in 1999. The trip occurred shortly after an Ottoman-era palace in Zoqaq al-Blat in Beirut was controversially transformed into a parking lot.

Many historic buildings in Dublin were demolished by developers in the 1960s and 1970s. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

Many historic buildings in Dublin were demolished by developers in the 1960s and 1970s. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

While in Beirut, the president of the Irish Georgian Society, Sir Desmond Fitzgerald, offered to provide support to APSAD to fight the demolition of historic buildings. The now-defunct Lebanese newspaper The Daily Star reported that at a dinner at the Sursock Palace to mark the end of the society’s tour of Lebanon, Sir Fitzgerald said that the tactics used by developers in Beirut were similar to those employed by Irish developers to demolish Georgian buildings in Dublin in the 1960s and 1970s.

“It’s the usual trick,” Fitzgerald was quoted as saying. “First the house is stripped of its roof, the building is allowed to deteriorate and then bully boys move in at the weekend to pull it down."

A row of Georgian houses in Dublin. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

A row of Georgian houses in Dublin. (Credit: Hannah McCarthy/L’Orient Today)

Sursock Cochrane’s own home in Gemmayzeh was badly damaged in the Beirut port explosion in August 2020. He was on the phone with his brother Roderick, who owns the Sursock Palace, when the blast happened. It badly injured his mother, Lady Sursock, who tragically died aged 98 a month later.

“I still have nightmares,” says Sursock Cochrane, who hasn’t returned to Beirut since the blast.

Sursock Cochrane is currently in the process of amending the title deeds to his own home on Rue Gouraud so that subsequent owners have to maintain the character of the building — “I couldn’t bear it if a skyscraper was built there,” he says. “It’s one of the last really beautiful areas in Beirut.”

It’s taken three generations for Lebanese people to realize that heritage homes in Lebanon should be protected, says Sursock Cochrane. “It’s 20-year-olds who have now realized what they've lost and that historic buildings have to be preserved.”