A girl on her way to school in Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today/File photo)

BEIRUT — Today is a rare day at the park for Ahmad’s two children, ages seven and eight years old, who have spent a long, “uncertain” summer in their house in Beirut.

It’s an early October day between rainstorms, less than a week before public schools across the country are finally set to begin again, on Monday, Oct. 9.

Though today they’re walking around the park and playing with their parents, the children had little to do all summer until they can, hopefully, restart the public school year — delayed for weeks after teachers’ strikes and slashed Education Ministry funding.

Another father, in southern Lebanon, says his teenage children have had to work all summer to save money for transportation to and from classes that, by the time they speak with L’Orient Today in early October, have still yet to begin.

When Lebanon’s summer holiday started in June, and students had three months to relax, the resumption of public school classes in the fall was not actually a given.

Empty classroom in a public school in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

Empty classroom in a public school in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

They already had a bumpy academic year last year, with public school teachers going on strike for months on end, leaving almost one million children “without an education,” according to Save the Children.

Still paid in the massively depreciated Lebanese lira, teachers have been demanding improved salaries and benefits since the economic crisis in Lebanon unfurled in 2019.

The Education Ministry recently announced that classes would resume on Oct. 9 — already a delay from the usual pre-crisis September start date. Meanwhile, for Syrian students, who attend Lebanese schools via a morning-afternoon shift system, the date for resumption of classes has not yet been announced.

‘They had to sell their gold’

A source well informed on the public school system, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told L’Orient Today that the school year is indeed set to begin on Oct. 9 as announced. Caretaker Education Minister Abbas Halabi has formed “a comprehensive plan where the academic year will be extended and will stretch on for 10 months, and the school day will be longer,” the source added.

They said that the ministry has submitted the plan to undergo study, though it still needs funding and a new law to allow the changed class schedules.

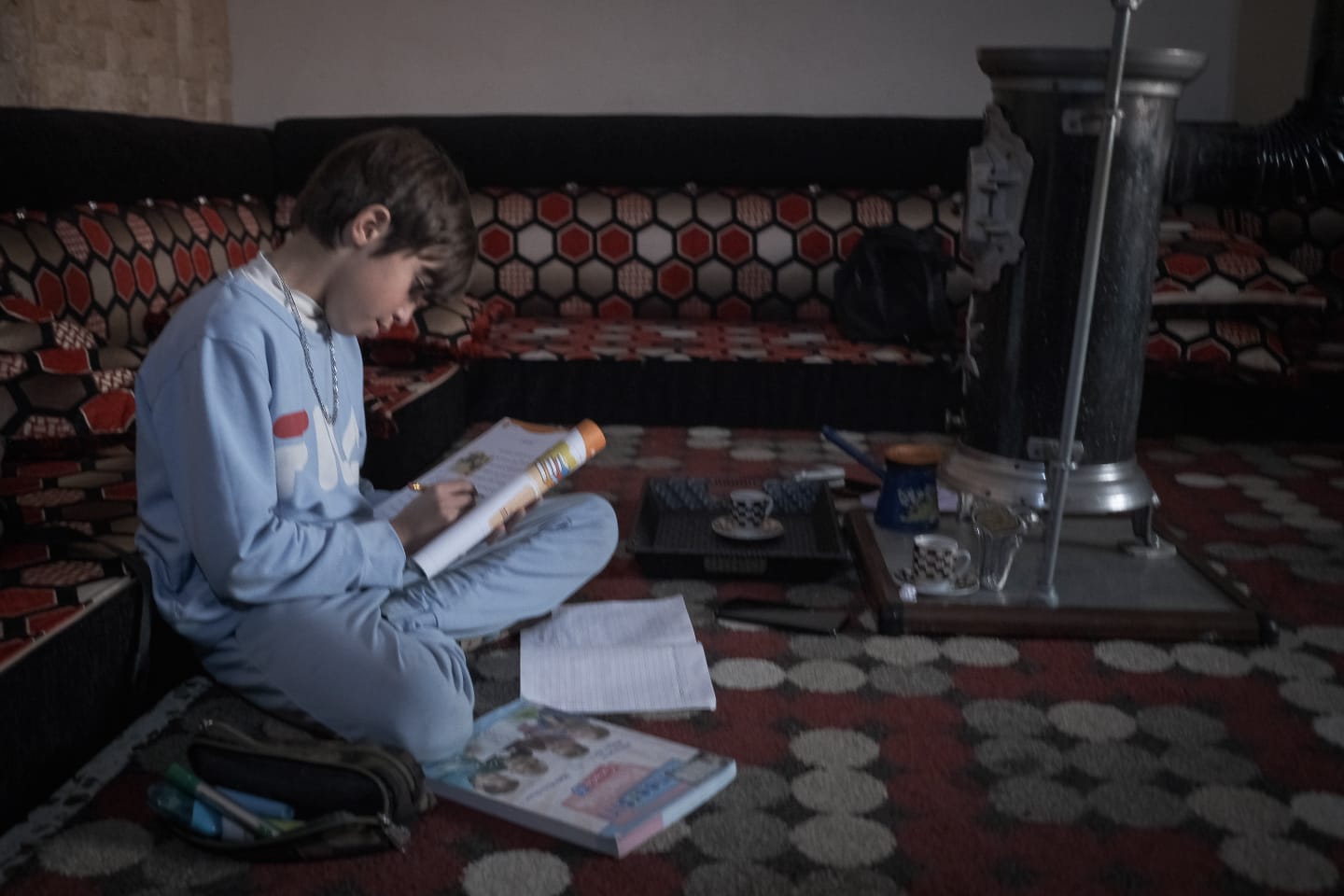

A young boy studies by the fireplace in his house in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A young boy studies by the fireplace in his house in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“We have been trying to reach the donors and international community since last year for funding to implement this plan and the answer has always been no. Lebanese students will not receive this funding,” the source lamented.

“Some poverty-stricken families are contacting the ministry and blaming the education minister, they’re saying they had to sell their gold to send their kids to private schools” instead of relying on the public education system.

Though private schools have already resumed teaching across Lebanon, dollarized tuition fees are burdening households in a country where more than half the population lives below the poverty line.

According to a World Bank Report, around 55,000 students moved from private to public schools between 2020 and 2021 alone, which has added more pressure on the public school system.

Over half a million children have already dropped out of school altogether since 2019.

A young school student clutches her toy and looks at her school certificate. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

A young school student clutches her toy and looks at her school certificate. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

‘My hands are tied’

Hussein Hammoud is a father of two middle school students in a public school in Nabatieh. He tells L’Orient Today that he and his family have had an “anxious summer.”

“It’s not easy to see your child’s future being threatened while you stand with your hands tied due to financial constraints,” Hammoud says, as his children will have to pay for transportation and stationary once classes resume.

Hammoud has been a taxi driver for over 20 years. Even in the best of times, his monthly income is no more than $350, he says.

Before the crisis, he would in the best of months make $1,000, and on the slow months around $600.

To get by today, he has to rely on the $200 his sister sends him from Canada monthly.

Hammoud’s two children, 13-year-old Abbas and 15-year-old Mohammed, spent their summer working at the local barber shop and saving money for transportation to and from school.

“Frankly, I also wanted them to learn a craft on the side in case they were unable to continue their education, but that’s the worst-case scenario,” Hammoud says.

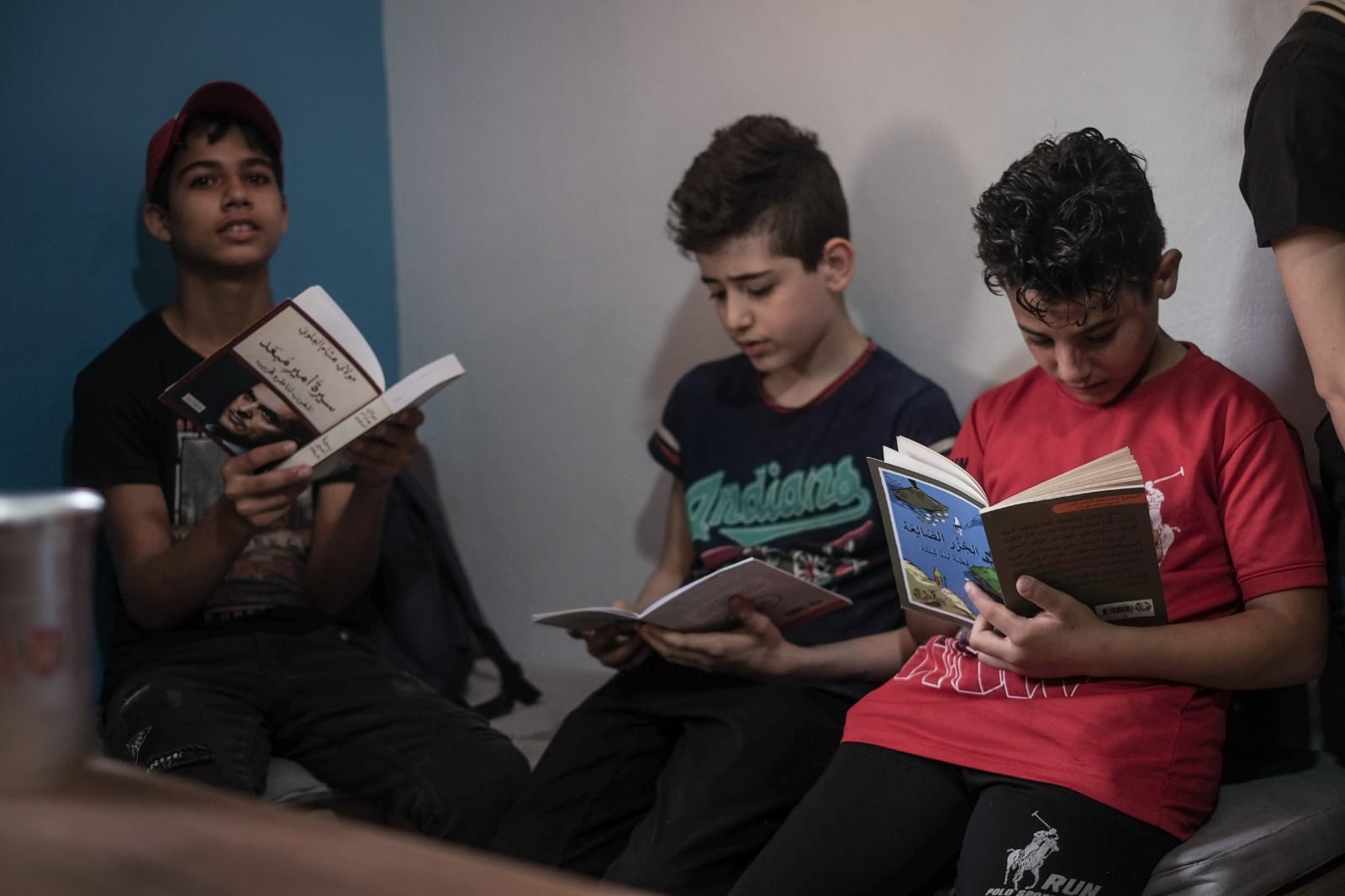

Students reading during their class. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

Students reading during their class. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

According to a UNICEF report, “three in 10 young people in Lebanon have stopped their education [since 2019], while four in 10 reduced spending on education to buy essential items like basic food and medicine.”

UNICEF estimated that around 13 percent of families are asking their children to work as a way to cope economically.

For now, though, Hammoud’s children spend their days after work swimming at the beach in Sour and playing volleyball with friends until the late hours of the night.

“They’re just kids, they can’t see far enough about just how much this crisis can affect their future.”

‘I was thinking of taking my kids back to Syria’

Ahmad, the father of two in Beirut, says he’s been considering taking his children back to his home country, Syria — at least there they could start classes again, he figures. He requested a pseudonym to protect his privacy.

“Despite almost over a decade of brutal war in my home country, I would have to say that the public school system there is not in shambles as much as the one here is,” he adds.

“My nieces and nephews have normal school years” in Syria.

A mother teaches young daughter at their home in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

A mother teaches young daughter at their home in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

His own children spent the majority of their summer “at home, video calling with their grandmother and young cousins in Damasus,” Ahmad says. “We went to Ramlet al-Baida public beach a few times, but it is extremely polluted and my son developed a severe rash so we stopped going.”

Today the family is finding some respite at Horsh Beirut, one of the city’s few remaining public parks. Ahmad’s wife and two young children take a walk while he sits cross-legged on a picnic blanket, sprawled on the grass.

“My wife only studied until the first grade and was unable to teach my kids at home, and I spend my day working as a plumber and come home late at night, way after my kids’ bedtime. My kids still don’t know how to read basic letters.”

A Human Rights Watch report, released in September, noted that most public school students are one to two full years behind their grade level amid an ongoing collapse of the Lebanese education sector.

A ‘miserable’ summer

“Even if the school year started [the teachers] will go on strike soon, and this fact has made my son miserable all summer,” Hani Salami tells L’Orient Today from his home in Sour.

Hani’s son, Issa, is a 12th-grade student, a “critical year as he has to sit for the official exams.”

Instead, Issa has been working on a construction site in northern Lebanon since last year.

“When the teachers would go on strike, he would call the head of the [construction] site and tell him he wants to join, but I want more than that for my son,” he says.

The government has made some moves to bring the strikes to an end. In August, Cabinet approved "dollar incentives" for public school teachers and allotted an initial payment of LL5 trillion "to ensure the start of the school year," caretaker Education Minister Abbas Halabi said at the time.

A student poses for a picture at an informal schools in a refugee camp in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

A student poses for a picture at an informal schools in a refugee camp in North Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today/File photo)

Teachers “have been promised that the incentives will be paid monthly and on time after the academic year kicks off,” Haidar Khalifeh, a public high school teachers’ union leader, confirmed to L’Orient Today, adding that teachers were promised five liters of gasoline per working day. Khalifeh’s union has met with Halabi, caretaker Finance Minister Youssef Khalil and deputy Banque du Liban Governor Wassim Manssouri on the issue, he added.

Khalifeh noted that the extended strikes have harmed students and teachers alike.

“We are fearful that the state won’t stay true to its words and pay us our salaries on time, but right now the only option we have is to start the academic year,” Khalifeh concluded.

The total amount of incentives needed for teachers this coming academic year is $150 million. The first payment of LL5 trillion — amounting to roughly $50 million at the parallel market exchange rate — should be enough to cover "three to four months," according to Halabi’s remarks in August.

In the meantime, Issa dreams of becoming an architect someday — a goal he’s had since he was nine years old. But his older cousin is now teaching him the school material he had to skip last year due to the teachers’ strikes and closures.

Every night after Issa’s shift at the construction site, the two young men climb onto their rooftop in Sour. There, they sit for hours on end smoking a few cigarettes, drinking sweet tea and studying schoolbooks.