Mohammad Hammoud, three days after his arrival in Lebanon. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin)

Upon first glance, the stark dissonance is immediately apparent. Mohammad Hammoud’s unassuming appearance, his calm demeanor and his composed responses seem incongruous with the notorious label that the American press has attached to him for decades.

The questions that linger are compelling: Is he truly guilty? Could he be the unfortunate victim of a miscarriage of justice, an unwitting participant in a poorly scripted narrative, as he vehemently claims?

Familiar with the routine, prior to commencing the interview with L’Orient-Le Jour in his brother’s living room, he politely requested to answer questions in English.

“I would feel more at ease, despite my proficiency in Arabic,” he explained.

Hammoud, 49, a man described as “one of the most dangerous terrorists in the world,” has recently been released after spending 23 years in US prisons.

Portrayed as the mastermind behind a Hezbollah network operating within the US, Hammoud maintains his innocence despite the allegations. In 2003, he received a sentence of 155 years for his supposed involvement in financing Hezbollah through a cell in the US.

Following an appeal, his sentence was reduced to 30 years in 2011. However, it has been reported that Hammoud received a further reduction of seven years for “good behavior” at the end of 2022.

“I was informed on Nov. 29 that the courts had decided to release me,” Hammoud said.

The US authorities have not officially commented on this decision. Contacted by L’Orient-Le Jour, the US Embassy in Lebanon declined to comment.

According to Nicholas Heras from the New Lines Institute, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington DC, it is believed that Hammoud’s release was likely part of a broader agreement between the US and Iran. This assumption comes as the two countries engage in indirect talks concerning the nuclear issue, with the matter of hostages being a central point of discussion.

In response to the situation, Rana Sahili, a spokesperson for Hezbollah, said, “We have no affiliation with him. This individual comes from a specific social environment and religious community.”

“However, you can reach out to him,” she added before providing the contact information of Hammoud’s brother.

Hammoud received a grand welcome last week at Rafik Hariri International Airport in Beirut, where his family and dozens of supporters eagerly awaited his arrival. Notably, he was accompanied on the plane from Chicago by two American federal agents.

As he stepped onto the streets of Tahwitat al-Ghadir [in Baabda district], he was greeted by hundreds of men who joyously carried him amidst the lively tunes of brass bands.

Yellow Hezbollah flags fluttered above them, and chants of “labayka Nasrallah” [we heed your call, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah] filled the air. In a symbolic gesture, sheep were ritually sacrificed, their blood staining the pavement, as a tribute to his return.

However, after three days, the initial frenzy subsided, and Hammoud settled in his brother’s building, where a portrait of him was displayed on the railings. Journalists, with a touch of humor, playfully referred to the location as “the mausoleum,” attracting their attention.

The entire village of Sorbbin in the Bint Jbeil district, the ancestral home of the Hammouds, honored their native son.

Hammoud left the village in 1992 at the young age of 19 to establish a life in the US.

Hammoud, born into a conservative and humble Shiite family as one of nine siblings, made a deliberate choice to seek exile in the US to pursue his education and establish a life for himself.

“As a Lebanese who experienced Israeli occupation and other challenges, I always recognized the biased nature of American foreign policy,” Hammoud said. “But apart from that, I held the belief that America was the greatest country in the world.”

This perspective resonates in the Middle East, where the US is often referred to as the “Great Satan,” while simultaneously captivating the region with a certain allure and fascination.

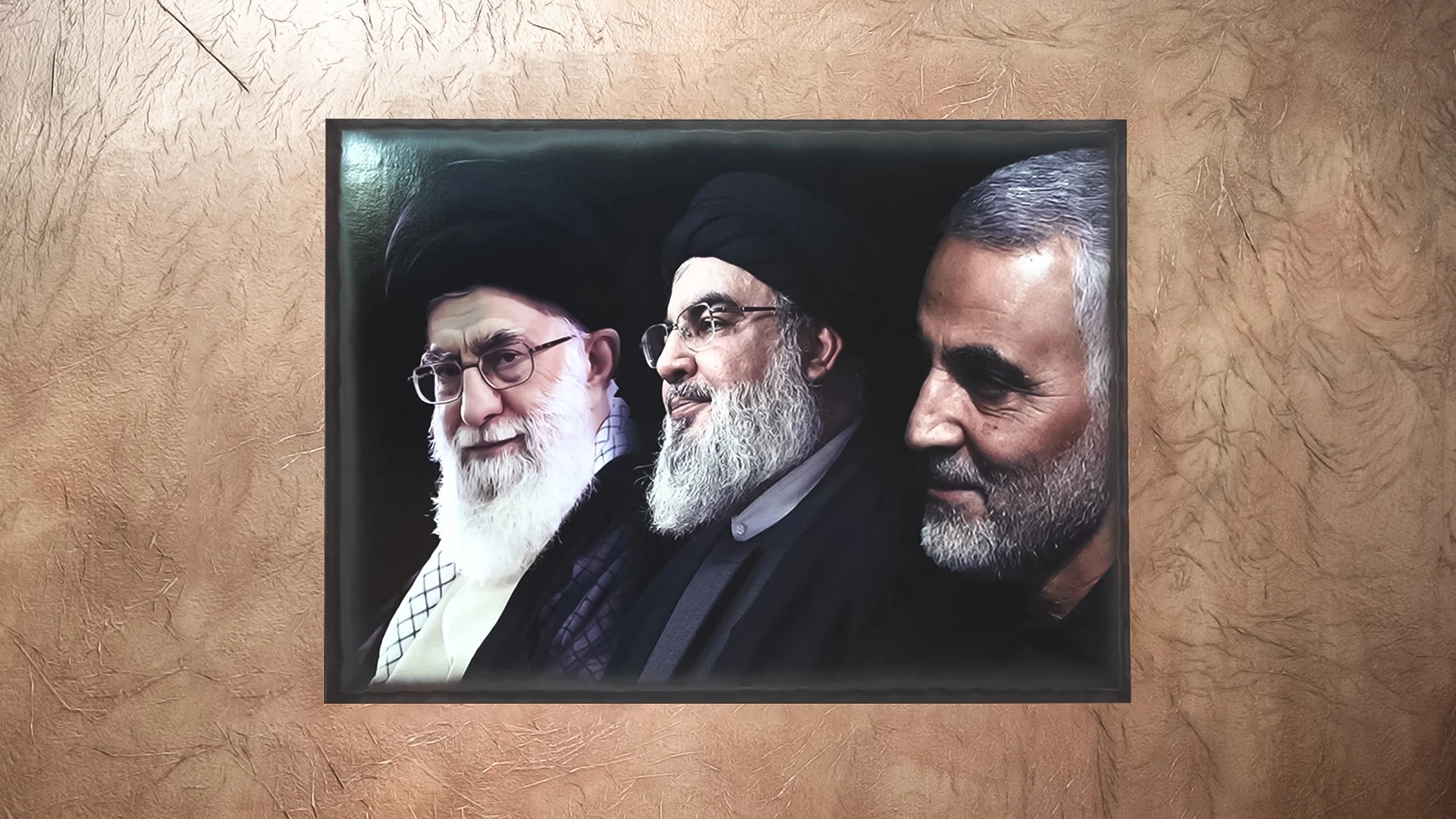

A photo of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and Iranian General Qassem Soleimani on the living room wall of Mohammad Hammoud's brother's home. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin)

A photo of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and Iranian General Qassem Soleimani on the living room wall of Mohammad Hammoud's brother's home. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin)

A Hezbollah cell?

The chain of events unfolded in July 2000, when federal authorities in Charlotte, North Carolina, initiated charges against 18 individuals, predominantly of Lebanese origin, for offenses related to cigarette smuggling, money laundering and immigration violations.

However, the case took a significant turn as US authorities began asserting that they had stumbled upon a Hezbollah cell.

“Hammoud’s arrest, along with that of his associates, was a direct outcome of ‘Operation Smokescreen,’ a groundbreaking collaborative effort between multiple American law enforcement and intelligence agencies. It was unprecedented at the time,” disclosed a US diplomatic source, speaking anonymously to L’Orient-Le Jour.

Hammoud defended himself against the allegations, saying, “Between 1996 and 1998, many Lebanese, Palestinians, and Yemenis started transporting cigarettes without paying tax.”

“I had my own shop, and I pleaded guilty to not paying tax. But then they built a case against me claiming that the profits from this sale went to Hezbollah, which is absurd.”

On June 21, 2002, following a five-week trial, Hammoud was found guilty and on Feb. 28, 2003, he was sentenced to 155 years in prison by a US district court.

The conviction was made under a 1996 anti-terrorism law, as Hammoud was charged with providing material support to Hezbollah, which the US State Department designates as a terrorist group.

According to US authorities, it is alleged that Hammoud unlawfully entered the US and operated an illicit cigarette smuggling operation worth $8 million. A portion of the profits from this illegal enterprise was ostensibly funneled to Hezbollah.

Hammoud’s brother, Chawki Hammoud, who is nine years older, also faced legal consequences. He was convicted of immigration fraud, cigarette smuggling, money laundering and racketeering.

According to a US diplomatic source, in the late 1990s, Hammoud led a cell that facilitated financial support to Hezbollah through the illegal trafficking of contraband tobacco between North Carolina and Michigan.

The source revealed that Hammoud orchestrated a complex operation involving the purchase and resale of contraband cigarettes.

“To conceal their activities, the group utilized counterfeit credit cards, checks and social security cards. Hammoud was involved in recruiting individuals to participate in the operation,” the source said. “During this period, the cell made efforts to maintain a facade of normalcy in order to avoid suspicion.”

Hammoud continues to vehemently defend himself against the accusations, even after more than two decades have passed.

“They couldn’t find a single piece of evidence to indicate that I was sending money [to Hezbollah], apart from in 1995 — before the 1996 anti-terrorism law which, among other things, banned fundraising for terrorist organizations and allows their assets to be seized — when I sent a cheque for $1,300 to the office of Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah [the Shiite scholar who died in 2010].”

“And yet they had all my bank documents from 1992 until the day they arrested me,” he added, insisting that the American justice system has made a mockery of his case without any concrete evidence of his involvement.

“My trial was the first trial of a Muslim just after 9/11,” he said, accusing the American justice system of making an “example” of him.

‘I wanted to show off’

In publicly accessible trial documents, there are photographs of Hammoud as a young man in Lebanon displaying his apparent sympathy for Hezbollah, a fact that he openly acknowledges.

One photograph depicts him as a teenager, holding an assault rifle in front of a portrait of Imam Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader. In another photo, he is shown kissing a man wearing a black turban, identified by American authorities as Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.

“I was a kid, there was a war on, and there was a Hezbollah office next door, so I wanted to show off. But as far as the second photo is concerned, it’s absolutely not the Sayyed [Nasrallah],” Hammoud said.

In 2011, the US Court of Appeals upheld all the charges against Hammoud but reduced his sentence to 30 years in prison.

During that time, US District Attorney Anne Tompkins claimed that Hammoud had allegedly orchestrated plans for the murder of the then-US attorney and the bombing of the federal courthouse in Charlotte — accusations he vehemently denied in statements to L’Orient-Le Jour.

A poster is displayed outside Mohammad Hammoud's brother's home to mark Hammound's release and return. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin)

A poster is displayed outside Mohammad Hammoud's brother's home to mark Hammound's release and return. (Credit: Mohammad Yassin)

For 23 years, Hammoud found himself confined within several high-security prisons. During his incarceration, he immersed himself in sports; avidly read books, particularly in English; and diligently studied the law. In fact, he even provided legal counsel to fellow inmates

“One day, a gang leader nicknamed Big Rock, who was serving a life sentence, tried to impress me and asked me what I’d done. I told him to open a magazine I had that mentioned me as one of the most dangerous terrorists in the world,” Hammoud recounted.

“The man was speechless, and I told him that it was obviously completely false, but this rumor about me actually protected me in prison,” he added.

Hammoud also recalled when he was detained with men accused of belonging to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group (Daesh). He questions why the prison authorities would place him, a Shiite associated with Hezbollah, among those with opposing ideologies.

In the living room where the interview was conducted, a composite photo featuring Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and the late Iranian general Kassem Soleimani, who was killed by the Americans in 2020, adorns the wall.

“I will always continue to support Hezbollah in its fight against Israel and humanitarian work in assisting the needy and the orphans,” Hammoud concluded.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.